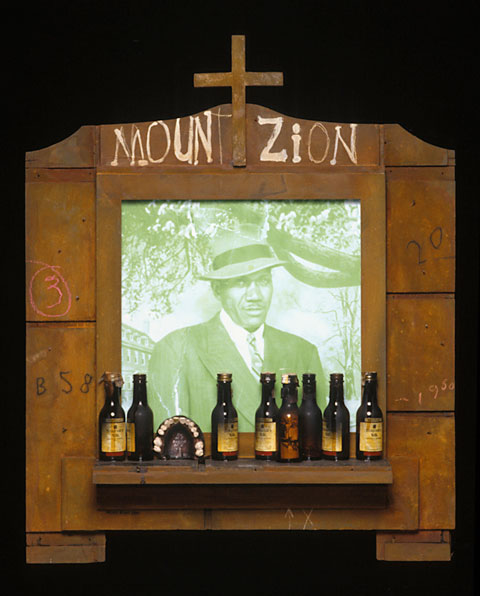

This work of Renee Stout (1958) is in the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art.

The imaginary world of Fatima Mayfield

Hoodoo Woman

By Elizabeth Pandolfi @girlseeksstory

When you go to a Renée Stout exhibit, be prepared to encounter two people. First there’s Stout, the artist. Then there’s Fatima Mayfield, Stout’s hoodoo-practicing healer alter-ego and the subject of an upcoming exhibit at the Halsey Institute, Tales of the Conjure Woman. Looking at the work that makes up Tales of the Conjure Woman, you’ll see Mayfield’s handwritten notes on seduction, her collection of roots and herbs in bottles and jars, models of hearts in torso-shaped wire cages, and paintings of various characters who people Mayfield’s world. The experience is one of looking through somebody’s else’s things — always a guilty pleasure — with an added spookiness that comes not only from the mystical nature of those mysterious objects, but from the ghostly presence of Mayfield herself.

And yet Stout does not come across as the type of person who has crafted an imaginary second-life as a hoodoo-practitioner. In her CP interview, Stout is down-to-earth and matter-of-fact, calling Mayfield her “alter-ego or character or whatever.” In other words, she doesn’t make a big deal out of it, despite the fact that Mayfield has been an integral part of her artistic life for many years. And before Mayfield, there was Madame Ching, another character who helped Stout explore the traditional African beliefs she draws so much inspiration from.

1990

Stout dates her interest in African spirituality to her childhood when she saw a small figure called a Nkisi Nkondi at a museum where she was taking art classes. Nkisi originated with the people of the Congo River basin and are believed to be inhabited by spiritual entities. The Nkisi Nkondi are a special class of Nkisi, which can be called upon or activated to search out wrongdoing or cause or cure sicknesses. Their appearance can be especially ghoulish because of the way they’re activated: by driving nails into them. Some are completely covered with nails, from their jawlines to their feet. It’s not surprising that such an image would stick with a person for years, even if only on a subconscious level.

And as Stout explains in an interview in the Halsey’s exhibit catalog, that’s exactly what happened. “The impact of that piece was so great that even though I seemed to have forgotten about it as I grew up, when I finally moved to Washington, D.C. in 1985 and discovered the treasures in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art, my excitement about that first Nkisi came rushing back.” Around this time, Stout also discovered a spiritual supply store that sold mystical roots and herbs, further stoking her interest in the subject.

She began seeking out practitioners and supply stores of various spiritual types in Pittsburgh, where she is originally from, and D.C., where she still lives. Many of the people she’s encountered practice Latin American-influenced spirituality like Santeria, which is a West African-Caribbean hybrid religion that’s also heavily influenced by Roman Catholicism. Then there’s Yoruba, the traditional religion of people from Nigeria, and countless other variations and adaptations. “They all have their basis in traditional African beliefs, although there’s a variation from environment to environment within the country, wherever you find the practices still alive,” Stout says.

One of the best known places to find those practices, of course, is New Orleans, even though much of the tradition has been bastardized for tourists seeking out made-in-China voodoo dolls and cheap herbal spells. Yet the fact that the tradition is out in the open greatly interests Stout. “As a culture they’re used to talking about hoodoo, but it’s more for consumption than anything that goes on under the surface,” Stout says. And that’s probably why it is so out in the open — the true practice of hoodoo or Yoruba or any other kind of African folk medicine is generally kept pretty quiet, she says. “It’s very hush-hush because it’s always been stigmatized, because we live in a culture that deems itself a Christian culture. So anything that is not in line with that is demonized.”

This is where Fatima Mayfield’s role becomes more complicated. In the world that Stout creates, Mayfield is a healer in the sense that she reads fortunes, prescribes herbal remedies and love potions, and helps people with their problems. But on a higher or meta-level, Mayfield can help those who come to see Stout’s work confront their own feelings about traditional spirituality. As she says in the catalog, “There are still many African Americans who have fears about my work — they feel that it goes against their Christian beliefs.” She elaborates on this statement during our interview.

“What has happened as far as the development of African-American religion and African-American culture, of course you have slavery when Africans were ripped from their own belief systems. When they were brought here, they were taught that everything they believed was like devil stuff, and they needed to be Christian,” she says. “So what happens is when people really start to believe that about themselves, the last thing they want to do is look at something that was from that history. And so, in a sense, to look at my work is to bring up issues that people want to bury.”

But this certainly isn’t true for most, or even many, of the visitors who come to Stout’s exhibitions. As with any art exhibit, the first draw is, of course, the art itself, not the symbolism behind it. “With contemporary artwork in general, whether it’s mine or someone else’s, people will sometimes gravitate to a painting or piece without necessarily knowing much about the content,” she says. “So unless they really obviously recognize something in there, you know, like a symbol or a figure or something that disturbs you, people usually will look at the work first and deal with it as an art object.”

For her exhibition at the Halsey, Stout has created almost all new works, although there are a few from between 2008 and 2010. All are related to Mayfield somehow. Eventually, though, Stout says that Mayfield will dissipate, as did Madame Ching. “It’s interesting because she developed out of my sort of shyness, and what she became was that projection of a person who was more self-assured than I was. But as I mature, as we all do as we age, I felt like I was growing more into her — but at the same time she’s a projection of the woman I hope to be,” Stout says. “So in some ways she’s her own energy, and it’s interesting because even though she’s just a projection of myself, I still almost feel like she’s there. It’s kind of a weird thing — I don’t even know how to explain it. It’s like this living entity that I hope to grow into, mature into.” And when she does? “I just think the work will go to a different level. Everything about my being will shift. I think it’s a growing process — it’s my growing process.”

This article is a review of her show last year in Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art. Copyright the author.

BIO

Renée Stout grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and received her BFA from Carnegie Mellon University in 1980. Originally trained as a painter, she moved to Washington, D.C. in 1985 where she began to explore the spiritual roots of her African-American heritage through her work. Inspired by the African Diaspora, as well as her immediate environment and current events, she employs a variety of media, including painting, drawing, mixed media sculpture, photography and installation in an attempt to create works that encourage self-examination, introspection and the ability to laugh at ourselves and the absurdities of life. Her vast exhibition history includes solo shows at Hemphill Fine Arts in Washington, D.C.; The Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, LA; David Beitzel Gallery in New York, NY and the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts in Pittsburgh, PA. She has also been included in group exhibitions at The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, PA; The Reginald F. Lewis Museum in Baltimore, MD; the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, GA; and Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.; among several others. She has been the recipient of awards from The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, the Joan Mitchell Foundation, the Bader Fund, The Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation and the High Museum’s Driskell Prize. Most recently, Renée Stout received the 2012 Janet and Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize.

Courtesy the artist and Accola Griefen Gallery, NY.