Rosalie van Deursen writes a personal report of the biennial in Senegal.

Jean-Philippe Aka takes the same event as a starting point to talk about the market for contemporary African art. Van Deursen concludes: “Considering Dak’Art as the most important international platform for established and emerging African arts and artists based on the continent but also in the African Diaspora, the international well-attended 11th edition seem to have succeeded”. Aka is convinced that many changes are necessary to make the African art market healthy.

A full immersion in the Senegalese art scene

Biennial Dak’Art 2014

‘What do you think of the biennial?

It is the first week of May and a young and energetic artist, Mady Sima, writes a question on his white boubou (traditional men’s costume) during a performance in a rural area in Senegal. He writes: ‘What do you think of the biennial? Mady asks the audience to reply to his question by writing a response on his boubou and also on a big black plastic wall that functions as a guestbook at his exhibition. The answers are divers. A visitor states: ‘’Artists must also decompartmentalise exhibitions, Dakar and Saint Louis should not be the only exhibition spaces and headlights of the biennial, rural areas should also be concerned, why not involve regional cultural centres in the biennial? “And someone else writes: “Exhibiting artists must further improve their speech and refine concepts, this is a great initiative!” Others have difficulties understanding what is going on: “I do not know what the biennial or Dak’Art means” and “The arts are not easy to understand it is for a small circle of people”. Mady Sima is very satisfied with the outcome of his performance in this small community named Keur Samba Kane. It is exactly the reason why he wants to bring the biennial outside Dakar to a society where people only know the phenomenon from TV or have never heard of it at all: “I want to raise awareness in the society, on multiple cases”. The works that he displays consist, among others, of canvas with plastic bags tied to it. He explains: “Plastic bags are everywhere on the streets in Dakar and elsewhere, each time people buy something they wrap it in plastic and just throw it away at home. A real waste and nobody seems to care or do anything about it”. He graduated from the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Dakar in 2009 and classifies himself as a conceptual artist. Mady is not the only artist in Senegal that wants to raise public awareness about modern society through creating art. It is a recurring theme within the Senegalese art scene.

Mady Sima Performance boubou at openingsceremony at Keur Samba Kane

Mady Sima Performance guestbook at openingsceremony at Keur Samba Kane

Mady Sima working in his studio

Mady Sima with two of his works in the background

Bustle in the city

While Mady Sima opened his exposition outside the capital, Dakar itself is buzzing and packed with the international and national art scene consisting of art critics, curators, artists, art historians and many others working in the artistic field. One meets, reunites and is above all curious about the selected and other exhibited works of art of the 11th edition of the Dak’Art biennial. Considering that there are a handful official ‘IN’ expositions and around 270 ‘OFF’ exhibitions one needs to select and plan a strict agenda to run from one opening to another. All the openings seem to be planned during the first week of the biennial which is not so strange since everyone wants to benefit from the bustle in the city.

Opening ‘Hommage to Mousthapha Dimé’, Galerie Nationale des Arts

Opening ‘Cultural Diversity’ at Museé Théodore Monod

Opening ‘International Exhibition’ at Village de la Biennale

‘IN’ versus ‘OFF’

The main events of the biennial consist of the Dak´Art ´IN´ sites for which you have to be selected as an exhibiting artist. The International Art exhibition is herein the leading exposition, curated by Elise Atangana (France/Cameroun), Abdelkader Damani (Algeria) and Smooth Ugochukwu Nzewi (Nigeria lives in USA). In addition there are tribute exhibitions featuring the works of Senegalese artists: Mbaye Diop, Mamadou Diakhaté and Moustapha Dimé as well as an invited artist exhibition with for the first time a strong focus on African sculpture. Completely new is the exhibition at the University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar, the so called Green Art exhibition. However, the so called ‘OFF’ exhibition sites form the largest part of the biennial. The organisation of the ‘OFF’ sites started in 2000 with only 50 exhibitions listed at that time to the large number of 270 sites today. The concept behind the ´OFF´ sites is that it belongs to everyone and gives the opportunity for all players in the arts and culture to present their work in a wide variety of places like restaurants, bookshops, galleries, companies, hotel lobbies, on the streets and so on.

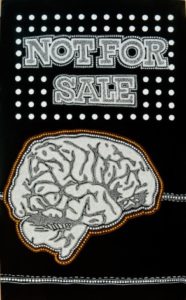

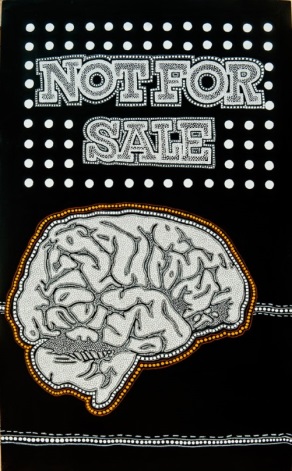

Not for Sale

A few Senegalese artists are selected for the International Art exhibition, such as Sidy Diallo, who shows his concern by the upheavals of modern society caused by globalization. In the works ´Renaissance 1´ and ´Not for sale´ Diallo stresses the vicious effects of the development race. ´Renaissance 1´ shows the Man in a primitive state, seated on a throne to signify the potential of continents like Africa. African countries are sadly often led by executive’s advantage interested in the crown – a symbol of authority. Construction or reconstruction of Africa can only pass through a strong and educated youth. ‘Not for sale’, deals with the African brain drain. Young people come to study in the West but never return to their home countries – countries that would benefit from their expertise. Sidy explains: ‘My work in general is to provide contemporary responses to the issues of contemporary development affecting the African continent; it is a work of pictorial compositions conceptual base consisting of points and routes´ (Catalogue biennial Dak’Art, 2014).

Sidy Diallo, Renaissance 1, 2013 Acrylic and pastel on canvas, 149 x 250 cm, courtesy of the artist © Guillau Bassinet.

Sidy Diallo, Not For sale, 2013, Acrylic and pastel on canvas, 147 x 243 cm, courtesy of the artist © Guillaume Bassinet.

Universal peace

Also dealing with a global issue is Senegalese Amary Sobel Diop who wants to restore and preserve a universal peace by showing the reality of the 21st century women who are delivering a fierce battle on human rights. According to Diop the world will acknowledge women as we acknowledge reason. With ‘Apologie pour la paix’, Amary Sobel Diop pays tribute to the women of the past few decades responsible for a fragile peace, maintained through their actions. Among other: Leymah Rigoberta Gbowee of Liberia, Yemen’s Tawakkul Karman and Aline Sitoe Diatta of Senegal and the West African sub-region. The portraits are made with a stitched-assemblage technique that Diop calls assembly couture and include etched biographies of each individual (Catalogue biennial Dak’Art, 2014).

Amary Sobel Diop, Apologie pour la paix (Apology for Peace), portrait of Lemah Roberta Gbowee, aluminium plates taken from spray deodorants, copper, wire, sewing, stitching, 130 x 105 cm.

Detail of the work above.

Universe of Women

Massamba Mbaye is a Senegalese curator and in charge of the invited artists’ exhibition that he provided with the title ‘cultural diversity’. He doesn’t want to refer to physical topography while speaking about cultures, but speaks about a mental topography: ‘Cultural diversity can expressively be demonstrated by creative diversity’. ‘Shared humanity gives an equal dignity to all earthlings. This is how the one is combined with the many… and vice versa’ (Catalogue biennial Dak’Art, 2014). In this exposition one of the few Senegalese women artists exposes her work: Fatou Kine Aw. Like the curator of this exposition, Kine Aw also despises the term ‘contemporary African art’. Kine: ‘We are all contemporary in this universe and of course people take over things from the environment they live in, consciously or unconsciously, and because I grew up and live in Senegal, makes me an African woman from the Sahel, but the art works are always the perception of the artist not of the topography’. In her work she translates from her own womanhood the universe of women in the Sahel: round shapes, beauty, tradition and modernity. She considers herself as a modern woman using an IPhone, computer and other conveniences of modern society, but at the same time she doesn’t want to forget the African tradition and in particular the ‘warmth from the African community’. The work reflects a vision of what could happen in the world. The world has become a village but one should not forget the richness of one’s culture. Senegal for example has an enormous ethnic diversity and therefore cultural wealth. Kine Aw finds it important that people take the good things of the new modern world but should strive for a balance between traditional values and modernity. One forgets it’s owns beauty. Africans want to be like Europeans and wear a Dior bag because they think it’s an Eldorado in Europe and the USA and that she finds very sad. ”They forget to be proud of who they are”. She sees herself as a counsellor as an ambassador of her culture; she hopes to encourage people to reflect on themselves. Kine Aw feels a responsibility to raise awareness through her paintings. “My paintings show that Africa is beautiful and that people should invest in Africa. That needs to be done in Africa itself”. She does not have eternal life, but the paintings do. “For now and in the future people can see what it’s like is here in Africa’. “L’Afrique est belle!” she says with tears in her eyes. “Unfortunately society is afraid of differences. Women should stop their blockade and crawl out of their shells. Women should not cultivate that they do not belong to the artistic environment”. In other words Kine Aw considers it a task of an artist to make people think and reflect.

Kine Aw, Civisme, acrylic and tar on canvas, 2013.

Multiple perspectives

Another young and vibrant Senegalese artist exposed in multiple exhibitions throughout Dak’Art is Barkinado Bocoum. Like Kine Aw, he graduated from the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Dakar and is also critical in his visions about modern society. His large scale figurative paintings are built up of small patches creating multiple perspectives. Barkinado explains with a serious expression: ‘everyone has different characters, for example happy, angry, sad … those are emotions that are all hidden in one person. This also counts for objects. Everything has multiple perspectives. THAT is the truth. Not only the outside of a person. That’s just one perspective’. His painting ‘Pat’ shows a cut up chess board where world leaders and the artist himself are the chess pawns. He wants to show that everyone wants to showcase its power and wealth to give sense to their existence and it tends towards the absolute even though we all know it’s an illusion: we are all in a game as a chess pawn.

Barkinado Bocoum, Pat, 2013, Mixed media on canvas, 300 x 450 cm

Barkinado Bocoum, Pat, 2013 (detail, artist in the middle), Mixed media on canvas, 300 x 450 cm

Barkinado also tells it’s not easy being an artist in Dakar because there are many artists, people do not buy, there are few collectors and the current politics of culture is only investing in folkloric art: ‘politicians are empty shells, they want to leave their mark’. One of the curators, Abdelkader Damani, confirms this view by explaining the absence of an active market for contemporary art in the continent and not many institutions that help artists either. He underpins that artists need to go to Europe or the USA to find people to buy their work. He hopes that events like the Dak’Art Biennial will open the African market.

Like many other artists in Dakar Barkinado Bocoum works at an art school to earn an income, but also because he finds it very important to teach the arts to the new Senegalese generation. He wants to push students to work hard, develop a vision and a way to express themselves. While being an art student himself he worked very hard and had many side jobs at the same time to survive. He lived in a very small room where he could not work other than on small size with pastel on paper. He explains that he didn’t have the means so he had to work small and couldn’t use expensive materials. It was only after he won the first price of ‘L’Afrique en question’ in 2009 and the ‘Prix de l’Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie’ at the Dak’Art 2010 Biennial that he could afford to move to a larger studio and work on large scale canvas with acrylic paint. ‘I remember well that I hung up the small paper drawings next to each other at an exhibition as if it was a large painting!’ And he stares and says: ‘I also want to teach my students pursuing their goals’. Barkinado Bocoum is very pleased with the Dak’Art biennial in his home country because it really helped him in his career. He explains: “It’s not only a way to expose my work to an international audience, but also a possibility to discuss with international art critics and other artists. They triggered me to work harder and reflect more on my work’.

Background Dak’Art biennial

Considering Dak’Art as the most important international platform for established and emerging African arts and artists based on the continent but also in the African Diaspora, the international well-attended 11th edition seem to have succeeded. One of its objectives is revealing to a wide audience that Africa creates and innovates and promoting new collaborations between Africans and those of other continents. Despite this achievement, people are always looking for development and change as Mady Sima showed with his performance. He preaches for a greater outreach of the biennial to the outskirts of the city and the Senegalese countryside. However, it should be remembered that the biennial was only originally established by the Senegalese government in 1989 and its first edition in 1990 was dedicated to literature but was soon reconceived as a contemporary art event with international exhibiting artists. As time moves on the biennial will develop doubtlessly. The Prime Minister of Senegal, Ms. Aminata Touré, also stated during the opening ceremony: “Today, we are entering a new phase of the biennial. Phase out where the universality of art gets citizenship. It is driven by a modernization that brings cultures in a process of mutual enrichment” (Dak’Art, 2014).

It is this modernization that Senegalese artists do not seem to take for granted. They reflect on the causes and consequences with their artworks using a wide variety of techniques and materials in order to raise public awareness about modern society.

Biennial Dak’Art 2014 opened on May 9th and runs till June 8th 2014.

Bio: Rosalie van Deursen is an independent Art Historian with a focus on African Art

—————————————————————————————————————————

Contemporary African Artists are “orphans” in the Market

The 11th Dakar Biennale (DAK’ART 2014) opened May 9th under the theme of “The Business of Art”. It was a wise decision of M. Babacar Mbaye Diop, the Secretary General, to choose an issue like that, if you consider the bad economical state of Contemporary Art on this continent.

Today the art market is global. But it is also local.

The effect of the lack of professionalism in certain emerging or becoming markets is not to be underestimated. Concerning African contemporary art there are plenty of serious researches and thesis but in terms of strategy, commercial policy and market efficiency, the artist’s state of affair is dire.

Olu Amoda, Sunflower, 2012, Courtesy the artist (co-winner of the ‘Grand Prix Léopold Sédar Senghor’).

Most of the artists are like “orphans”.

The problem with African artists today is not their lack of true talent, even if there is still room to improve, it is hard for them to survive with a minimum of comfort. We cannot just focus on a tiny group of blue chip artists like El Anatsui, William Kentridge, Wangechi Mutu, Julie Mehretu, Marlene Dumas and a few others. We are speaking of artists from a continent with 54 countries. Otherwise, worldwide recognized and respected for its cultural production.

Marcia Kure, The Three Graces, 2012.

There are many entrepreneurial attempts at founding galleries, establishing art dealership or representing artists as an agent or in matching artist’s studios or art events. However the lack of professionalism hurts the market. This is mainly due to poor experience and no expertise and an inability to penetrate the large western market. Good will alone is not sufficient. Likewise the origin of the “dealer” is never a guaranty of success.

It’s a legitimate ambition for any African contemporary practitioner to aim at the global market. However, it’s not legitimate to be taken advantage of. The relationship between Africa and wealthy western countries must evolve. To reach this goal we all acknowledge the need for our art market to build a strong backbone with proper marketing, distribution and the like.

What I am pointing out it’s not the lack of involvement of the many good willed people. It’s not about their origin either. I am convinced that the more people believe in contemporary African art the better for the artists.

The key issue is the major unbalance between professional actors (handful) and improvised dealers (majority).

Without any serious commitment on the part of political and economical leaders, the contemporary African market will remain a niche for long time. The artists are the victims.

Ismaila Fatty, Trial with Jute, 2011, copyright Mattia Lindback, courtesy the artist.

The loss in revenue is invaluable for African contemporary art.

It is sometimes difficult to be considered as a niche. Finding a serious report on the African art market is hard. The most known one available is from Artprice: http://www.artprice.com/artmarketinsight/557/Contemporary+African+art

This is a good example of the state of the market as it implies that no one knows the real value of a piece of art. Moreover it is difficult to find out qualitative information that would help create perspective in order to understand a market, a market that needs investors. As regards to the secondary market, it is safe to say it doesn’t exist in Africa, with the exception of South Africa, Nigeria and Morocco.

As regards to the individual involvement local art players are more valuable and courageous with their efforts and investments than those based abroad who present themselves as specialists. They are only surviving thanks to acquisitions by a tiny group of collectors, mostly expatriates. Like in the past. They have no significant resources to improve the local market and they also don’t have constant and dedicated support from local authorities. Yet, they are conscious of their limits and deal with it.

The solution must come from Africa.

John Amkofrah, Peripeteia.

Looking at the past, during the Italian Quattrocento even Lorenzo de Medici with his financial power and his influence was not the only collector and patron who achieved the “Italian renaissance” and who fed the artists of this glorious period. Recently, the acclaimed collector of contemporary African art, Jean Pigozzi massively contributed to the arising of African Contemporary art. Yet he hasn’t yet succeeded in realising the same effect on the market. We often hear about collectors like Lionel Zinsou, Sindika Dokolo, Alami Lazraq, Emile Sipp, Robert Devereux, Gervanne & Matthias Leridon and a few others. Will they help to organize the necessary structure our art market needs? If they don’t, the actual uncertainty in the market will jeopardize the value of their collections. The true risk is the slowdown of motivation. There’s no miracle but only professionalism, structuring, knowledge and experience.

Aren’t creative and genius minding born in every culture? I think yes…

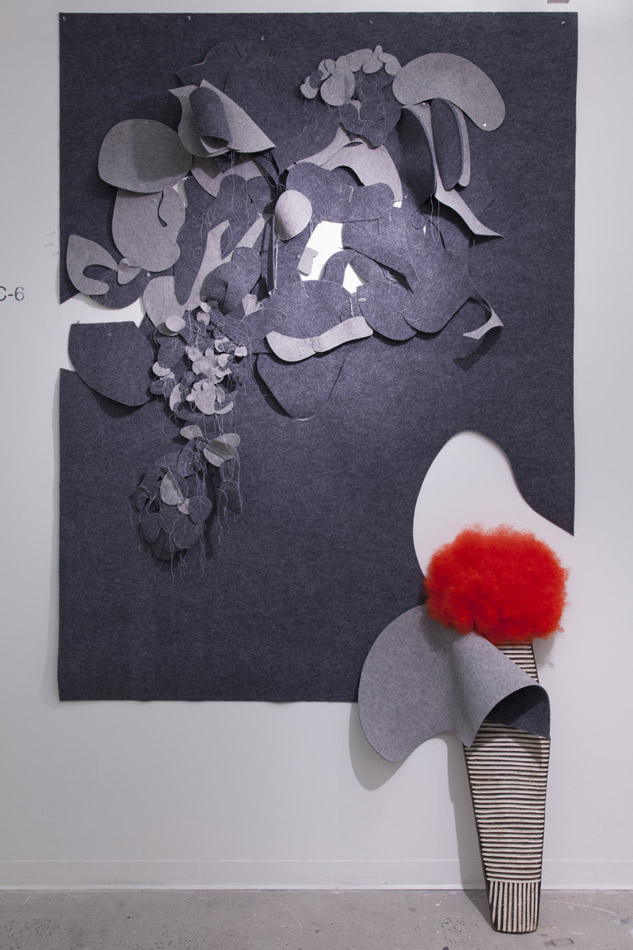

Mustapha Dimé, installation.

Must see in Dak’Art 2014:

1. Morocco’s Pavilion: a group show – ‘Abstractions Legitimise’- curated by Michelle Desmottes & Mostapha Romli, at Place du Souvenir;

2. John Amkofrah’s video installation at the Village of the biennial;

3. Marcia Kure’s installation at the Village of the biennial;

4. Simone Leigh: “My dreams, my works, must wait till after hell…,” at the Village of the biennial;

5. Retrospective of the work of Moustapha Dimé, curated by Yacouba Konate at the Galerie Nationale;

6. Georges Adeagbo at the Librairie 4 vents;

7. Bouna Medoune Seye, participant of the group show curated by Afrikadaa Magazine at Biscuiterie de la Madina;

8. Iba N’diaye’s retrospective at Musée du CRDS/Point Sud, Saint-Louis, curated by Malick Ndiaye and Laetitia Pesenti.

Brief bio : Jean-Philippe Aka s a Paris based art dealer and consultant. He is in charge of the ‘heartgalerie’ & ‘HANDPICK/JP AKA’ for 15 years. Offices in New York and Johannesburg. Collaborations with artists, galleries and institutions worldwide.

Text + photo: signed article is original content. It benefit from the legal protection of copyright