Anthropologist James Clifford argues that art museums must learn from anthropologists; for example, to see objects as a process and not just as a product. The use of the object adds value. This is exactly what happens when the Kabra mask dances and gives the ancestors an opportunity to manifest themselves. Masks make sounds, says Clifford, they move, but they lose that ability in museum display cases. Once they end up in a museum, they stop their function in society.

Annemarie de Wildt of the Amsterdam Museum tells the story of the creation and the acquisition of the dancing Kabra Mask.

Kabra dance-mask, Boris van Berkum, 2013. Lacquered polyurethane, textile 66 x 40 x 40 cm. Collection Amsterdam Museum. photo Erik Hesmerg

KABRA MASK

A dancing museum object

One of the most remarkable objects in the collection of the Amsterdam Museum (1)is the Kabra mask. It was created in 2013 by Rotterdam artist Boris van Berkum, with Winti priestess Marian Nana Markelo as his muse. Kabra means ancestor. The mask accompanied Nana Markelo at the yearly commemoration of the abolition of slavery, dancers danced with the mask at a Winti bal masque, the mask was added to the collection of the Amsterdam Museum, and it kept on dancing. (2)

Loss of sculptures

Captured Africans were not allowed to take any objects, masks or sculptures on the slave ships that brought them to the Americas. During this Middle Passage the African sculptural traditions of images and masks representing the ancestors got lost. In the Dutch colony of Suriname the enslaved developed the Winti-religion in which the ancestors play an important role. The religion was suppressed by the Dutch colonizers. It was forbidden by law to perform Winti rituals. “He who commits idolatry shall be punished with imprisonment not exceeding three months or a fine not exceeding one hundred dollars.” (Art. 540 of the Surinamese Penal Code). Only in 1971 was Article 540 deleted.

Marian Markelo and the Kabra mask. Keti Koti celebration: national commemoration of the abolishment of slavery, 1 July 2013, Oosterpark Amsterdam – photo James van den Ende

Winti-priestess Nana, born in Suriname in 1956, deeply regrets the loss of sculptures. She visited Ghana and other West-African countries where images representing the ancestors still play a role in ceremonies and rituals. Nana wanted to reintroduce this sculptural tradition in Winti. During one of our conversation she said: “My ancestors told me: go and find someone to help you with this”. On the shores of the Maas River, where she conducted Winti-ceremonies, she met an artist who had his studio there. Boris van Berkum (1968), a 6th generation Rotterdammer (3), told me about their first meeting: “her ancestors tapped her on the shoulder and said: that’s the one you need.” For a whole year Boris participated in Winti events and celebrations to get to know the religion and its rituals.

Re-appropriation

Van Berkum calls himself a neo-artist. Just as artists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries appropriated classical and gothic art, he fuses the styles and forms of various periods, cultures and religions in his sculptural groups. His sculptures are made of ceramic and bronze, but also of epoxy-paste and even fondant icing. On previous projects he had worked with 3D scanning. Van Berkum and Markelo developed the concept of the African art liberation front. Instead of demanding the restitution of ritual objects from ethnological museums – a hot debate since the 1960’s – a more contemporary and practical solution would be to liberate them from the colonial showcases by making 3D scans and re-introducing them to communities as 3D prints of the original objects. The new collection encourages an African Renaissance in the Winti culture.

Storage rooms

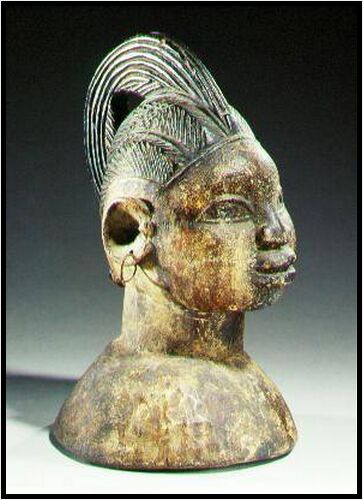

The Africa Museum in Berg en Dal, now part of the Museum of World Cultures, embraced the idea and welcomed Nana and Boris into their storage rooms to select some objects for scanning. Nana communicated with her ancestors, while choosing the masks that would be transformed into 3D prints. They were scanned in the museum’s auditorium with an Artec 3D scanner. And thus, an old mask from the Yoruba region would re-appear as the 21st century Kabra-mask. (4)

Egungun mask, maker and date unknown, Afrika Museum collection nr. 481-5 – Height 9 cm x width 17,5 cm x Depth 20,5 cm. Wood, iron

Scanning of the mask in the Africa Museum

3D print of the mask on the cloth for the costume

3D print of the mask on the cloth for the costume

Ancestral spirits

For the Yoruba their ancestral spirits are much more than just dead relatives. They are sought out for protection and guidance and they are expected to keep an eye on the traditional rules of conduct within the community. One of the ways in which they communicate with the living is by their manifestation on earth in the form of masked spirits known as Egungun. The Egungun appears as “a robed figure which is designed specifially to give the impression that the deceased is making a temporary reappearance on earth” (Idowu 208) The beautiful series of Egungun dancers by Beninese photographer Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou portrays their individual personalities and their power as visitors from the world of the dead. (5)

Bigger impact

Boris van Berkum made several changes to the Egungun mask from the museum collection. It is much larger than the original. In this way it can make a bigger visual impact. It appeared on television during the memorial on July 1st, 2013 in the Oosterpark in Amsterdam. There is also a practical reason for making it larger. The mask (on a wooden structure) can be held by the dancer, who, like the Egungun dancers, is hidden behind a costume with see-through gaze cloth before her eyes. Van Berkum also added cloth to the mask itself, following the hair comb shape of the original sculpture. The cloth is a traditional Indonesian batik cloth, a so-called ‘pers’. In the 19th century this hand made cloth inspired Dutch textile factories (for instance Vlisco) to create a mass-produced fabric with ‘African’ designs that became very popular in West-Africa. The colors, white and blue, are the traditional colors connected with death and mourning in Suriname. The Kabra mask was printed in white polyurethane and lacquered after applying gold dust.

Winti priestess

Marian Markelo is an important person in the Dutch Surinamese community. Every year during the keti koti celebration on July 1 she performs a libation for the ancestors. Keti Koti means breaking of the chains. Since the inauguration of the slavery monument in Oosterpark, created by Surinamese sculptor Edwin de Vries in 2002, this is the place where the national commemoration is held. I had met Nana Markelo several times during the preparations of a slavery intervention in the exhibition on the Golden Age in the Amsterdam Museum (2013). We added quotations from descendants of slaves to the exhibition.

Marian Markelo’s quote was one of them. “When I walk along the canals, I often think: part of this building belongs to me, because my ancestors worked hard to make it possible. Unpaid work”. On May 5th, 2013 the museum hosted a Keti Koti meal where 60 people from different backgrounds ate and talked about the heritage of slavery. At this occasion Nana also made a libation for the ancestors. At that moment I realized that for her, and other Surinamese people, the ancestors, the souls from the past, the ones who suffered slavery, were a real presence.

Libation by Nana Markelo, during Keti Koti meal in the Amsterdam Museum, May 5th, 2013. Photo Monique Vermeulen/Amsterdam Museum

Ik ben niet te koop

The appearance of the Kabra mask during the commemoration on July 2013 immediately intrigued me. Later that year I met Boris van Berkum and we started a conversation about the creation and the various performances of the mask. (6) He told me about the Ik-ben-niet-te-koop (I am not for sale) campaign of the Aban foundation that develops ‘visual art as a spiritual utensil’. (7) The dancers of ‘Untold’ created a choreography around the mask that would be part of a Winti Bal Masqué in the Laurens church in Rotterdam. Other occasions where the mask could appear would be Kabra Neti evenings where the Surinamese community would get together to communicate and dance with the ancestors.

Amsterdam Museum

I proposed that the Amsterdam Museum would acquire the mask for the museum collection. Apart from the esthetical value, there were various arguments for the acquisition. The object made its first Amsterdam appearance in 2013: the commemoration of 150 years of abolition of slavery. Journalist Liesbeth Tjon A Meeuw called the co-operation between a white artist and a black Winti priestess one of the most important impetuses to reveal the shared history and collective responsibility for the process of healing the colonial past. Furthermore, the mask represents a new, or rather renewed, element in Winti, a religion that has many followers in Amsterdam. Equally important is the way of production: the 3D printing technique, that enabled the‘re-appropriation’ of an object that was, as some people would say, ‘stolen from Africa’. In general 3D printing will have an enormous impact of our relation to objects and we can only begin to gasp what that will mean to museums.

Of course I did not want this recreated mask to disappear in the glass cases and storage of the Amsterdam Museums. It is a spiritual utensil, and I felt it should be allowed to continue dancing.

Masks make sounds

In the midst of the acquisition process, I attended a lecture of the anthropologist James Clifford at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Clifford argues that art museums must learn from anthropologists; for example, to see objects as a process and not just as a product. The use of the object adds value. This is exactly what happens when the Kabra mask dances and gives the ancestors an opportunity to manifest themselves. Masks make sounds, says Clifford, they move, but they lose that ability in museum display cases. Once they end up in a museum, they stop their function in society.

Within the museum, the possible acquisition of the Kabramask let to discussions about collecting, our role within society and how strict we should apply the regular rules for loans. At the Amsterdam Museum we are experimenting with a new category of objects which we call the useable collection (gebruikscollectie). The mask could be labelled as such. This new designation would allow other people than curators and conservators to handle it. There was support for the concept from other curators and director. The collection department initially was more hesitant. The sometimes heated discussions in the museum dealt with questions like: what if it gets dirty, would blood be sprayed on it during rituals and should that be cleaned or not? Does the object need to go into the hypoxic cell every time it has been out of the museum? A secondary objection was: it’s too much work, too unclear who is responsible for what, money, and administration. But we were positive and able to find solutions. The mask forced us to think about the fundamental questions: what do you want with these objects, what role do they play in the museum and what role the museum plays in society?

Dead or alive?

Anthropologist Markus Balkenhol, who recently received his PhD based on a study of the legacy of slavery, has embarked on a new research project where the Kabra mask will be one of the cases. (9) In this way the Amsterdam Museum itself is now the subject of ethnographic research into our values and norms, and the way we deal with objects. Our way of relating to objects is totally different from the way Marian or the dancers relate to the mask.

Markus Balkenhol observes art handlers and technicians of the Amsterdam Museum, who are installing the Kabra mask in a glass case, June 2013.

Referring to Arjun Appudurai’s concept of the social life of objects, anthropologist Rhoda Woets posed a fascinating question in Standplaats Wereld (10) Should the Kabra-mask, which will be travelling between the museum glass cases and ritual ceremonies, be considered as an object that is dead or an object that is alive? In what ways will the mask be loaded with meaning? Exactly these questions make this acquisition such a fascinating and ongoing process.

Winti bal masqué

While at the museum we were discussing, the mask continued dancing. For example at the Winti bal masqué in Rotterdam. It was a very interesting and hybrid occasion: a Winti celebration – some people went into a trance – dance group ‘Untold’ danced with the mask, musically accompanied by ‘Black Harmony’ and there was an Antillean carnival group. Boris van Berkum performed as DJ Chantelle.

Winti Bal Masqué, Laurens-church Rotterdam, March 15, 2014.

In June 2014 the mask danced at the Public Library in Rotterdam. I witnessed the way the dancers of ‘Untold’ – especially Vanessa Felter, who dances with the mask – dealt with the object. She told me that she feels like a different person when she put on the mask. “The mask tells me what to do.” Van Berkum had made a beautiful golden pillow for the case that contains the mask.

Kabramask on golden pillow. Rotterdam Public Library, June 2014. Photo Raoul Klebach

Boris and textile conservator Lisca discuss the installation of the mask. Photo Annemarie de Wildt

The conditions of transport/loan had been established: an (easy to handle) cardboard box. In June the museum celebrated the arrival of the mask with a meeting about its creation and its use that started with a song by Markelo.

Nana Markelo and Boris van Berkum at celebration of the arrival of the mask in Amsterdam Museum, June 27th, 2014. Photo Monique Vermeulen/Amsterdam Museum

After the meeting the mask was packed and transported to the Muiderkerk for a Kabra Neti, a meeting for and about the ancestors. Again the mask danced, this time surrounded by a whole church full of people with blue-white clothes. Some of them were possessed by ancestors.Two days later, the mask danced in Rotterdam, also at a Kabra Neti.

Kabra Neti at Muiderkerk Amsterdam, June 27th, 2014. Photo Annemarie de Wildt

On July 1 the mask was again at the national memorial in Oosterpark. It accompanied Marian Markelo, as she walked around the slavery monument. The Kabra mask has become a part of the commemoration ritual.

Libation at the monument, June 1st, 2014 – photo Annemarie de Wildt

Libation at the monument, June 1st, 2014 – photo Annemarie de Wildt

The Surinamese community is positive about the Kabra mask. “I did not know I had missed it. When I saw the mask for the first time I got shivers up and down my spine” said an elderly Surinamese woman when she saw the mask for the first time in 2013. The Kabra mask connects the Surinamese presence in the city and the heritage of slavery to the narrative of Amsterdam, whose inhabitants have played a great role in slavery in the 17th and 18th century. The city now houses many descendants of the enslaved. Together with the artist and the Winti priestess the Amsterdam Museum is very curious about what people, stories and events the Kabra mask will bring to the museum, to the city of Amsterdam and to the world.