“We can expand art to the extent that when we talk about art, we are speaking of a conscious, creative approach that is in response to images, and through response, creates its own images. Art thinking, art behaving, art conversing, art writing- these are activisms of art production that make use of our innate creativity in decolonizing and re-imagining our space.”

Thuli Gamedze on how art can function within activist spaces.

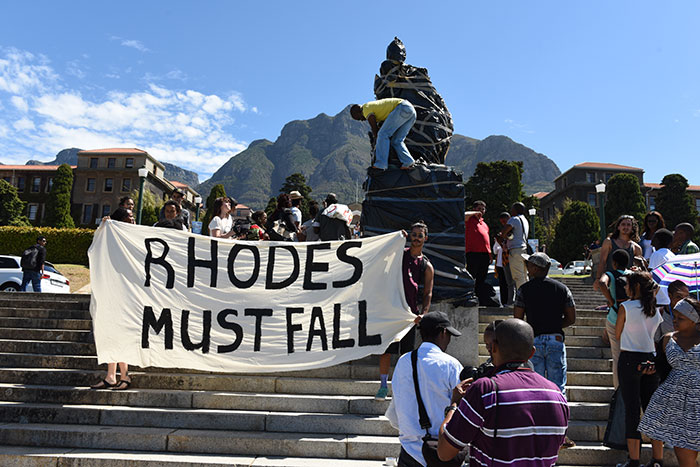

Statue of Cecil John Rhodes, Copyright photo: SABC.

Reclaiming Creativity: Decolonization as Art Practice

Eurocentric institutional fine art training and education in Cape Town, South Africa has provided me with both an interesting and challenging lens from which to navigate the current political climate of the country. In 2015, the space of higher education has been subject to incredibly radical critique from Black students nationwide, and using this ‘fine art’ lens- one that confused, blurred, and sometimes invisibilised my position(ality) as a Black woman- I am interested in the inevitably political nature of ‘creative’ education and engagement.

In addressing the crossovers between my understanding of art practice, and my understanding of a decolonial approach, it becomes important for me to think around what it is about the nature of art that is relevant and essential to the nature of decolonization. In posing questions like- What constitutes an image? And how is it that images function outside of the fine art environment? – this article aims to acknowledge the collaboration of the creative and the political, and how this collaboration births new symbolisms and new ideologies. In looking at contemporary South African student movements, and in particular the ‘MustFall’ phenomenon, the text hopes to add to a wider conversation around political art practices.

One shift in popular consciousness here has been a new hyper-awareness of the visual, and the way in which images and symbols function in South Africa, a country that is essentially still run as a colony. The pervasive western colonial symbolism in our public spaces is a dominant but ghostly presence, which is incredibly silencing for oppressed voices. Our country is littered with these colonial ‘heroes’- white men who stole land, enforced western law, religion and ideology, and killed Black people, amongst a range of other organized structural damage. In Cape Town, the dominant and persisting culture is in celebration and commemoration of histories that do not include us, and in fact, are structurally reliant on the historical exploitation of Black bodies.

In early 2015, directly as a response to this culture of structural violence, various forms of student protest began- protest, which I will argue that, was centered on a new kind of politically aware art engagement, production and practice.

The ‘MustFall’ Image: Destruction and Institutional critique as creative intervention

Copyright photo: Michael Hammon.

Copyright photo: Michael Hammon.

The RhodesMustFall movement was popularized by one of its initial projects to get the statue of Cecil John Rhodes removed from its central location on the University of Cape Town’s upper campus. The movement brought with it a sharp consciousness of the way in which imagery has the power to subjugate and to violate, with Rhodes being one of the most atrocious villains in African colonial history. It is evident, through the media coverage of the RhodesMustFall movement, that there was a serious lack of sincere engagement with the fact that Rhodes, the bronze, was only a representation of the kind of society that we live in- of the fact that Rhodes, the notion, is the pervasive voice of contemporary South Africa, the voice we oppose. Appropriated by the press, our trajectory was framed as a tunnel-vision campaign for the removal of a statue as the over-arching solution to the removal of a regime.

However, it soon became evident through the spread of ‘MustFall’ rhetoric, most notably in the #FeesMustFall campaign (for free education in South Africa), that a new image, an alternative to pervasive Rhodes symbolism, had emerged into public imagination. This MustFallness is an ideology that I understand as one speaking to decolonization (the destruction of the colonial structure, ideology, etc) as a way to make space for new ideas, and new ways of being. In this sense, the word standing before the ‘MustFall’ phrase always speaks to the notion of ‘Rhodes’, and the colonial legacy of South Africa. In the case of #FeesMustFall then, ‘fees’, the notion of wealth-exclusionary education in the colony, directly addresses the problems of an unequal status-quo.

What I am getting at with this background is that such a campaign relies on a collective image. This image is not a statue, or a traditional art object, but a phrase that is formed through response to violent ideology, a phrase that symbolizes pain and anger, and that symbolizes open space for something new. ‘MustFall’ is a phrase, an image, a symbol, and we might even speak of it as an art discipline, not painting or photography, but a discipline of creative and risky thinking, and a discipline of mobilsation and activism, based on the desire to see new images, and to create new symbols. It is an art practice, and a discipline with scope for radical change.

Art as Symptom

In addressing these weighty issues of symbolism, therefore, our thinking should seek to examine the existence of imagery, of art, as always a symptom and reflection of a certain socio-economic and political climate. Therefore, when we engage with images, we are engaging with the status quo of society, and in this sense, we might think around art practice as a catalyst for the mixture of all disciplines and knowledges. If we think of art in this manner, we approach an art practice that attempts to encapsulate and respond to violence creatively, using new modes of expression and learning. We use a collective image, a ‘MustFall’, to express our distaste and pain for the art we are used to living around. It is a fluid notion, an image that is characterized by its growing trajectory and multiple pretexts. It has little to do with the art institution because it puts into practice discourse that is usually deadened by the gallery space.

Of course, this mode of understanding art has new implications for the role of ‘the artist’, ‘the viewer’, and society at large, because it means that we are forced to deal with art outside of the institution, and to engage with the images that actually affect us all. The gazer and the object of the gaze become far less distinguishable when we understand ourselves as creative beings, as thinkers and makers, and as respondents to creativity itself.

Copyright photo: Trevor samson.

Art Institutions and the ‘Claim’ of Creativity

There are a number of possible responses to the fine art institution, and to me, the most important are responses that, rather than focusing in on the exclusivist ‘mysticism’ of institutional fine art practice, choose to look outside of it and acknowledge humans as creative beings that function and survive largely through our relationships to imagery, whether or not within the fine art setting. The necessity in investigating the way in which the institution seems to have claimed to have ‘specialized’ creativity into a discipline, is thinking through how we might de-specialize creativity so that we can play with it more consciously as a political tool.

We evoke imagery everyday through conversation, through text, through thoughts and dreams, and we respond to imagery that we see daily in the media, in advertising, and in our private and public spaces. Without creativity, we are unable to navigate the world, or imagine the world. However, some ‘creativities’ are dominant, while others are oppressed, forcing us all to understand and navigate public and private spaces according to the dominant white patriarchal capitalist imagination- an imagination which invisibilises Black bodies, trans bodies, queer bodies, differently-abled bodies- ‘other’ bodies. With these notions in mind, the necessity to destroy this ‘popular’ imagination and recreate one whose project is the liberation of oppressed peoples becomes evident, and we might begin to then understand the processes of this deconstruction, critique and re-examination of the existing ‘creative’ archive as an art practice in itself.

To me, breeding a culture that seeks to switch on and conscientise an extremely starved public imagination, is a politically informed creative project, placing emphasis on the art practice that exists all around us, and in a sense de-legitimizing the art institutional space, which attempts to hold and circulate creative knowledge only within its own bounds. This new imagination is a collective project and it attempts to move beyond the obsessive individualization of western art practice- whose style of self-reflexivity is limited to the personal, rather than to the relevance of the personal in relation to the collective and to larger systems of power.

Forward to what?

Perhaps it is in collective learning and educational exchange that we might find a ‘role’ for a politically engaged artist. Of course, in a communal learning space, we all become makers and viewers, writers, sellers, buyers, curators, and narrators, and then we can take art to allude to creative response and exchange as its very ‘objectness’, as we have seen with the ‘MustFall’ image/ artwork/ creative notion/ conversation. If we seek to truly understand art as a discipline with the potential to engage all and every subject matter, then will this kind of conscious image-engagement destroy the white cube, a colonial construction that segregates ‘art knowledge’, and dilutes its potential to catalyze and mobilize real change? #FineArtMustFall?

Somehow though, I am more inclined to engage in new art practices, which in their subversive processes indirectly address the problems of the ‘art object’, and the fine art institution, but which take as their primary concern, the creation of something new. Can we understand an art practice that is ongoing, performative, and immersive, one that takes as its departure point art as both catalyst for engagement, and art as the engagement itself?

From here, we might start to understand un-learning processes that seek to produce new ways of being and functioning in community and society, as creative processes, and as tools in engaging with the world, and engaging the world. We can expand art to the extent that when we talk about art, we are speaking of a conscious, creative approach that is in response to images, and through response, creates its own images. Art thinking, art behaving, art conversing, art writing- these are activisms of art production that make use of our innate creativity in decolonizing and re-imagining our space.