What took me by surprise back then, and what I tried to articulate in my answer, is that I was surprised that someone would be surprised that someone “with my background”, angry with and personally hurt by colonialism and slavery, could have an affectionate relationship with Dutch paintings from the 17th century. And yet, I feel at home with Pieter de Hooch’s The Country Cottage. I also feel at home at Paramaribo’s Waterkant. Both places pull me in with equal intensity, as if by teleportation. Both emotions: affection and anger towards two opposite phenomenons from one and the same historical period do not rule each other out, they coexist. Inside me there is no opposition. There is no true opposition.

Artist Dineke Blom tries to answer the question how an artist with a Surinamese background can have an affectionate relationship with Dutch art from the 17th century.

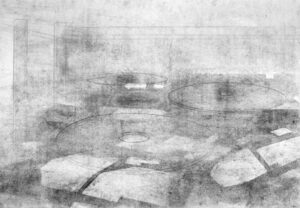

Landscape, 2003

First published: September 6, 2020

Country Cottage on the Waterkant

I travelled to Detroit, USA, in 2013 to give a lecture about my work. In the lecture, I discussed the various ways in which 17th century Dutch painting works as source material for my own drawings. During the proceeding Q&A, someone in the audience stood up and asked: how does someone like me, “with my background” (I was born in Suriname, my father is Surinamese) relate to works which are considered the epitome of Dutch culture, and “Dutchness”? The question took me aback.

The topic had never been relevant for me as an artist. It so happens that from a previous long term residency in the US I had learned that in the US I am identified as black. However, this is not necessarily how I identify myself. In Holland I am considered Dutch, without a hyphenated identity, although it is true that during some first-time encounters people ask me the perennial question: “but where are you really from?” On the other hand, and equally unpredictably, someone I have known for ages may never have realized that I am part Surinamese. Remarkably though, when it comes to my work, in Holland I have never been asked a question like the one I was asked in Detroit. Not even now, when postcolonialism is a hot topic in the realm of visual art and elsewhere. I am very much interested in discussions about the topic but my work is not capital P political. I remember giving my interlocutor in Detroit a somewhat vacuous answer, something like: “my Surinamese background does not play a crucial role”. After all, I “simply” feel at home with those paintings from the Dutch 17th century.

But why was I taken aback by the question? I have experienced moments in my life (I shall mention a few in a moment) when I was acutely and simultaneously aware of my Surinamese and Dutch backgrounds. On one occasion, I realized – to my own surprise – the ambivalence of my own feelings towards the Dutch 17th century. I was travelling to South Africa in 2015 to visit my son, who was studying there. In preparation for this trip, my first to South Africa, I had been reading about its history. This confronted me once more with Holland’s role as a colonizing power during the same period that has been branded as the “Golden Age”, epitomized by those 17th century paintings. All of a sudden, I could identify with the Detroit question. I imagined myself presenting my work to South African spectators and the thought hit me that in such a setting I could very well be asked: “you’re partly from Suriname, right? And that’s a former Dutch colony, right? You’re immersed in 17th century Dutch culture, don’t you get angry? After all, that same period includes colonialism and slavery, right?” I could imagine a similar setting, in Suriname, for example, with similar questions being raised by a Surinamese audience. And indeed, due to my personal background, I do get angry over Dutch colonialism and slavery. It hurts to be confronted with these issues, with the injustices and violence. However, in my studio, I do not have an issue with paintings from 17th century Holland. As an artist my emotions are straightforward: I love and admire the paintings of that particular period and the world of ideas, including the science and philosophy that it includes. This leaves me with a problem, an internal opposition. How do I integrate two conflicting emotions, one very negative and the other very positive, toward one and the same period, if at all? And can I?

For me this question links up – both within and beyond the realm of visual art – with the concept of “home”, of “feeling at home”. What do I mean when I claim that I “simply” “feel” at home with Dutch paintings from the 17th century? I shall try to answer this question through talking about my own work, and via examples from various different artistic disciplines.

I want to first expand on a number of the “moments” I referred to earlier:

USA

I am travelling through the Deep South with a friend in the late 1980s. In New York City, our point of departure, I had felt at home. The atmosphere was cosmopolitan and even though everyone there considers me black (which, as I’ve mentioned, is not always the case in Holland), I can identify as both black and white. Here in the Deep South, the environment is completely different. It in no way reminds me of New York, let alone Europe. We drive through towns which lack a main street but have a gas station and shopping mall, plus a church on every corner. Strangely, while I observe the transformation from New York to the Deep South from inside our camper, I am overwhelmed by a sense of a homecoming, because all of a sudden I see so many black people. I feel the heat coming in through the open window. There is the familiar sight of folks loitering and leaning against cars, and I see church-going ladies with their hats and starched dresses. This sight is so Surinamese, by which I mean this sight evokes the Suriname of my childhood. It seems that the farther away I am from what I consider my “natural” cultural habitat, New York, the stronger my sense of coming home is.

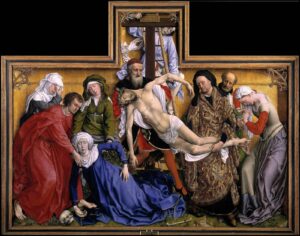

Rogier van der Weyden, The Descent from the Cross, ca. 1435

MADRID

While a teacher at Amsterdam’s Gerrit Rietveld Academy I am on an excursion to Madrid. For days now I have been in the company of over a hundred students, and together we have visited an endless string of museums. At one rare moment I am on my own, wandering through the Prado. I descend into the basement, and all of a sudden I am facing a colossal painting by Rogier van der Weyden. In a split second my sense of alienation, triggered by socializing for days on end with a faintly familiar group of people in an unfamiliar environment, is gone, and I feel an overwhelming sense of coming home.

AMSTERDAM

I bike home after a day’s work in the studio. My brain is on automatic because this is my daily routine. From the corner of my eye I notice someone on the sidewalk, someone resembling my uncle Dolf, the brother of my (Surinamese) father. Instantaneously, I find myself in Paramaribo, along the city’s Waterkant, its main street which runs alongside the Suriname River. This sense of dislocation is not by force of memory. Rather, it feels like an instant teleportation to the other side of the world, to a place which feels overwhelmingly familiar to me.

RIJKSMUSEUM AMSTERDAM

I am facing The Country Cottage by Pieter de Hooch. I am immersed in it: I am in the garden; I stand in its light as a figure that belongs in the scene. The sensation mirrors my experience of being teleported to Paramaribo’s Waterkant that time when I saw uncle Dolf’s doppelganger.

Pieter de Hooch, The Country Cottage, 1663-1665

My dealing with The Country Cottage as an artist has given direction to my work over many years. Something about this painting triggered me, and there must be some key as to why I was so attracted to it. At first sight the content, unassuming and accessible, held my glance: a garden; three figures seated at a table; a woman bent over a water pump. The level of realism obscures a deeper level at which this painting works. My gut feeling was that, rather than the iconography, it was the painting’s abstract elements that had pulled me in. For a long time, I wondered where my focus lay exactly.

The Country Cottage seems to imply that you, as a viewer, are included in the intimacy of the scene – how could you imagine otherwise? The light, so inviting and reassuring, spreads gently over every detail. What I remember most vividly from seeing this painting for the first time is that it hurt. At the same time I was perplexed by a dual sense of proximity and distance. There I was in the museum, but at the same instant I was there, in a familiar place, at ease in the painting. Back in my studio I began to draw, first with The Country Cottage and later on with De Hooch’s The Linen Chest as points of reference.

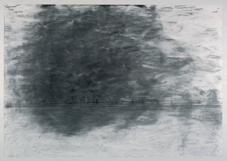

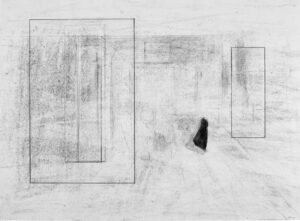

In due course I came to understand what I aim for in my own work. I am searching for an image alright, but an image for what exactly? The Country Cottage evoked a sense of intimacy. This is no shocking discovery, and neither is the sensation of being immersed in the scene. What is crucial about my dealings with The Country Cottage is that I realized that I myself have been trying to capture in my drawings an image for the concept of “home” and what comes with it. On the one hand, intimacy, generosity and accessibility, and, on the other, an awareness of feeling both an insider and outsider. This has been my focus. In the aftermath of “the Detroit question” the theme of home became more urgent to me, and its reach wider than I had imagined possible. I came to realize that my drawings, dating back to the series Salt&Soap (2002-03) [figs. 1,2,3] are, in a sense, simulations of “home”.

Fig 1: Dineke Blom, Untitled, after Hendrik Avercamp, 2005, 100 x 70 cm, pencil, graphite, charcoal on paper

Fig 2: Dineke Blom Untitled, after Pieter de Hooch, 2009, 102 X 72 cm, graphite, charcoal, pastel crayon on paper

Fig 3: Dineke Blom Untitled, after Jacob van Loo, 2013, 171 x 83 cm, charcoal, pastel crayon, pencil on paper

Dineke Blom, Untitled after Pieter de Hooch, 2003, 65 X 48 cm, pencil, graphite, charcoal on paper/Untitled, after Pieter de Hooch, 2009, 102 x 72 cm, graphite, charcoal, pastel crayon on paper

The drawing Untitled, After Pieter tde Hooch is a case in point. It depicts an open space which the viewer steps into, mentally, by crossing the foregrounded rectangular frames. The pentimento is thick, thus enveloping the separate pictorial elements in an intimate bubble. With hindsight, I see my drawings as visions of what, ideally, for me, home should invoke – space, openness and intimacy. I made all these drawings in my studio. That’s obvious, one might think, but to me the continuity of working in the same space is crucial. In my studio a parallel universe comes into being, a simulation of real life. There I can “relive certain themes – by selecting, enlarging, decreasing, compensating, shifting – in a different dimension”, to paraphrase from a biography I recently read.

Thinking about this image of the intimate bubble as an iteration of home… How much freedom does it allow for? How far can one stretch its protective cover before it snaps? How secure do you feel and how much risk can you take, and is it worth trying? Safety and risk are a balancing act. In the 17th century paintings which speak to my imagination I notice the precarious relationship between the two poles.

The fragile aspect of existence can be unsettling, but it can also create something playful and featherlight. I find an example of the latter in Charles Ives’ music. I was working in my studio when something playing on the radio caught my attention. It turned out to be a fragment from Ives’ fourth symphony. It was as if the orchestra was determined to go at it full blast. At the end of the piece I learned that the origins of this particular fragment lay in Ives’ childhood. In the small town where he grew up he had once seen two brass bands marching towards each other, and when they eventually intermingled they kept on playing. What surprised me in the fragment I heard was the fact that two separate melodies were being played by the orchestra, as if two orchestras had sat between each other. I have observed a comparable clash, as fascinating but with forces that intermingle irreversibly, near the island of Vlieland near the Dutch coast. There, the North Sea and the Wadden Sea meet each other. Another example, well-known, is the stretch of water off the coast of Cape Town in South Africa where the Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean run into each other. In my work, the anxious and the more lighthearted view of the fragile nature of our existence intermingle.

The parallel world of the studio shifts my attention from my own mood to the way in which the drawing is emerging. I feel comfortable maintaining a certain level of detachment in my work process. This may explain why I incorporate quite a few intermediate steps before I start on the actual drawing part. As I hope to have made clear, the path to the act of drawing is paved with emotion. That emotion fuels the process. But as the work progresses I shift into a different kind of involvement. More indirect, contemplative and analytical, and focused solely on exploring my source material, i.e. a specific painting from the Dutch 17th century.

The outcome is a collection of work sketches which I then edit on my computer. It is only once I have this reservoir of visual material that I can shift my attention to the empty sheet of paper and start drawing. The preparatory steps enable me to fully focus on the emotion, the mood and atmosphere which are emerging from the drawing at hand – with an emphasis on the word emerging. It is not planned beforehand. I want the dynamic quality of image production to linger on long after the drawing is completed, so that the drawing really comes into being when one looks at it. I aim for the image to keep the eye of its beholder active. There is no narration, there is no symbolism or references of another kind, there is only the image.

I think about the 17th century paintings that underpin my drawings. But these paintings do not ultimately narrate a story. To decipher them I must reach beyond iconography and painterly virtuosity, mastery and technique. I reach a perceptual level and it is there that I truly connect with them. There the world of De Hooch and his contemporaries and the world I live in are one and the same. When I realize this I feel quite close to De Hooch. Of course, I will never sit in the garden of that country cottage, but in my own garden I sit in that same light, I feel the same wind on my skin, and hear the trees rustling. We share this, this actual life of perception, and experience it with the same tools, our senses. As Heraclitus says: “If all the things that exist became smoke, the nostrils would be able to identify them”.

Dineke Blom Untitled, after Daniël Vertangen and after K.Malevich, 2018-19, 110x 89 cm, watercolor on paper

In Madrid, in the Prado, the unexpected encounter with Rogier van der Weyden’s triptych and the ensuing sensation of coming home was deeply comforting, and also a confrontational experience. The experience was disorienting but it did not truly throw me off course. What fascinates me is how different people handle situations that may sever them from their home. An example that has stuck with me is provided in a text by Piet Mondriaan. Mondriaan’s painterly work has no direct influence on my own work. However, his search for words he can use to communicate his ideas about his new direction in art encourages me to think about how existential the concept of home (in the sense that it is a familiar place that one shares with others) is to him.

The particular text I am talking about finds Mondriaan writing a three way dialogue between Y, X and Z (they are introduced in this non-alphabetic order; “Y: Lay-man. X: Naturalistic painter. Z: Abstract-realistic painter”). They take a stroll through nature, “from the countryside towards the town” (my translation). They comment on the scenery, but mostly they bring forth their separate views on art and how to express these views through art. It is a rather awkward exchange which continues over many pages. I gradually became more and more fascinated by the stubborn way in which Z, whose ideas reflect Mondriaan’s views on art, expresses his ideas. Whenever his companions have moved one inch closer to his viewpoint he comes up with more subtleties, which in turn provokes more resistance. He will not let his case rest. Mondriaan’s writing style is rather stiff, but this antagonism in the dialogue gives the exchange extra urgency. There is no room for stylistic embellishment here, nothing will distract from the content. I sense an existential loneliness in Z’s (really Mondriaan’s) urge to convince his companions, and in his persistent groping for the exact words to formulate his views on art. As far as I am concerned, he realizes that perhaps he will not win them over. Not forsaking his radical ideas, Z must tread an unknown conceptual territory all on his own. Home is about our very existence. Mondrian’s text makes this clear once again.

The ‘Detroit question’ has always stuck with me. It only became urgent in the period leading up to my trip to South Africa, when I saw myself and my work through the eyes of imagined South African and Surinamese viewers. I reflected on the 17th century from two different perspectives. How would these relate to each other? One perspective related to my artistic identity, the other related to my Surinamese background. The person in Detroit who confronted me with her question did actually connect the two: “you with your background” in combination with the 17th century. Indeed, it is food for thought, a starting point for further research.

What took me by surprise back then, and what I tried to articulate in my answer, is that I was surprised that someone would be surprised that someone “with my background”, angry with and personally hurt by colonialism and slavery, could have an affectionate relationship with Dutch paintings from the 17th century. And yet, I feel at home with Pieter de Hooch’s The Country Cottage. I also feel at home at Paramaribo’s Waterkant. Both places pull me in with equal intensity, as if by teleportation. Both emotions: affection and anger towards two opposite phenomenons from one and the same historical period do not rule each other out, they coexist. Inside me there is no opposition. There is no true opposition.