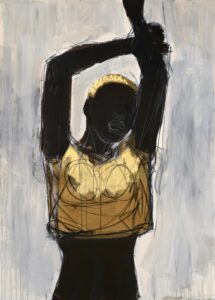

Ferrari Sheppard

So Bright, 2021

About:

“This thing of form, I think that much of what happens and what one becomes is definitely an outgrowth of what one feels. Regardless of the establishment that exists, but there is a richness that can be discovered if one has that kind of insight or becoming and searching… It is discovering what one can do in paint, what one can achieve, what visually excites you and what you want to see that hasn’t been done, you know. ”

Norman Lewis, founding member of Spiral

Four Moments Around the Sun with Ferrari Sheppard

Text by Kristina Kay Robinson, March 2021

In Brent Hayes Edwards’s The Practice of Diaspora, Edwards introduces the reader to the French term décalage, referring to a shift in space or time or the gap that results from it, and applies the term to describe the way in which members of the Black diaspora share similar conditions of oppression yet often find ourselves on opposite ends of the political spectrum—for example, Black American writers seeking solace from Jim Crow in Paris, while simultaneously Africans were struggling against French colonialism. These countering political locations create tensions within our diaspora, but Edwards does not see these sites of difference as global movement killers. Citing the work of Stuart Hall on the practice of “articulation,” “a process of linking or connecting across gaps,” which (says Hall) always forms “a ‘complex structure’… in which things are related, as much through their differences as through their similarities,” Edwards says that these disparate locations are, like joints, sites of potential forward motion. Dark Bodies, Bright Crest by Ferarri Sheppard seeks out and embodies these linkages and divergences of the diaspora with both abstraction and figuration, and stories that are narrative and lyric. Black people’s lineages are multifaceted, layered, contradictory sites of constant regeneration even as they are obscured by dominant cultural narratives on both sides of the ocean. Sheppard calls to mind these characteristics through his process of combining subtle acrylic layers with bold razor-sharp charcoal lines creating a dynamism on canvas reflective of the cultures from which his subject matter emerges.

Paeches, 2021

What to share, what to keep– how to both prepare and spare the children? Where is the beauty when you find yourself, your people, so often in a hell on earth? On both sides of the Atlantic Black people have had to reckon with systemic violence and disenfranchisement from both our ethereal and material cultures. Yet, the creative impulse of the people has served to foster and preserve a fugitivity of mind and spirit across generations. Art from the diaspora emanates, at its finest, when it concretizes the ethos and pathos of our collective humanity for both better and worse. Ferrari Sheppard’s Dark Bodies, Bright Crest shines by resting itself in the material of daily life while reaching into the ether to bring us closer to the cosmos. Lilacs in Spring sets the beauty of the natural world against the blackness of space, mind and body. The invitingly serene yet resolute figure in the portrait beckons us to not only behold, but to belove the gifts before us. Life is hard but it is not fruitless and this work by Sheppard calls us to reckon with the pain and glory of it all.

“If you are not a myth whose reality, are you? If you are not a reality whose myth, are you?”

Sun Ra, Prophetika Book One

I.

The Bakongo cosmogram, associated with the peoples of present-day Bas-Zaire, Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon and northern Angola organizes the life cycle of the universe and the human being into four moments around the sun. In the Congo cruciform, God is conceptualized at the top of the cross with the dead located at the bottom. The four points of the cruciform symbolize the four moments: adulthood, childhood, elderhood and ancestral transformation. This cosmology separates the universe horizontally in two: ku nseke (the physical world) and ku mpemba (the spiritual world). Between them is a wall, a door, a threshold, a line–kalunga. The kalunga line has been traditionally associated with the Atlantic Ocean, where the living cross over and become dead . The only way back is to recross it. In Ferrari Sheppard’s, Dark Bodies, Bright Crest subjects, both human and natural, journey through this cosmogram, cross and recross the thresholds of time and space, and riff on established conceptions of shape via his distinctive use and command of the line. Working In the tradition of abstract expressionism, Sheppard deconstructs the figure and ironically, in the process, returns the subjects to their humanity. A diaspora often rendered and considered only as a set of politics, Sheppard takes the descendants of the “bright continent” and renders them as people in the fullness of their intellectual and spiritual complexity.

The vertical line that bisects the Bakongo cosmogram functions as a link between the peak of high noon of life and the midnight of ancestral transformation. In Anansi, Kwaku Ananse, the legendary sometimes-man, sometimes-spider character of Ghanaian folklore is personified via the relaxed yet imposing figure who is its subject. Anansi, the child of heaven and earth, is seated upon a golden throne. The figure is not overtly gendered, evoking also the vertical line of the Bakongo cosmogram, that everlasting connection between men and women. Anansi is the tie that binds rather than alienates us from one another and the layering of cosmologies and mythologies of the diaspora is a particularly potent form of syncretism. The spiritual ground drawings of the diaspora are evoked subtly by Sheppard through the slashing of his lines through the canvases. In the Ghanaian myth Anansi spins a golden thread to reach the heavens. There Anansi asks his father for the permission to bring the stories to humanity. In Sheppard’s iteration, Anansi, the figure, also holds the stories of many times, many families, many peoples. Anansi changes shape, changes stories, makes the necessary mischief to keep humanity innovative. The figure rests their hand on their chin considering what to tell us, next.

Cobra calls to mind more of the diaspora’s mythology. Striking a similarly relaxed yet authoritative pose, the figure in Cobra directs our eyes both to the 24-karat golden throne and the sharpness of both the lines of Sheppard’s abstract figuration and the subject’s aesthetic. The tassels hang elegantly from an oxblood pant, the foot is positioned to reveal a well-constructed black boot. In the African traditional religion of Vodou, Damballah is the serpent father of the sky and always accompanied by his companion Ayida Wedo, the rainbow. A primordial deity and regarded by some believers to be the first thing created by God, all following creation commenced via Damballah as emissary. Shedding the serpent skin, Damballah created all the waters on the earth. Damballah, the serpent, he moves between land and water, giving it life, and through the earth, uniting the land with the waters below. In Cobra we see this marrying of energies, a continued syncretism of mythologies, as the throne sits against an almost wave like kalunga line, or snakeskin.

II.

Like It Is and Sweet Thing foreground Sheppard’s study of black and gold as colors, as motifs of history–their flesh and blood material manifestations. The mind is represented in abstraction and in the concrete aesthetic of black paint. The gold is 24 karat providing texture and concrete value considerations. The psyche and the body of both figures are deeply in tune with the influence one has on the other. Considering the pose and composition and the conjuring of both a woman’s vanity and throne, one can see the entire cosmogram of the Bakongo in these two paintings — all four moments — morning to night, birth to death (dawn, noon, sunset and midnight) presented in their regality without romance or spite. Both Kalima and Tasha call similar emotions to the fore. Frenetic beauty accompanied by inner serenity; they form a symbiotic pair.

Red Chair invites and reminds the viewer to never forfeit the ability to love. The closeness of the family that the painting depicts is as visceral as is the pulsating red. The throne in the painting is revelatory of the deeply felt ties that bind one human being to another. Many cosmologies and deities meet again here to find respite in one another’s existence — to teach one another how to love. The painting’s intersecting lines echoing the intersecting lines of the Kongo cruciform, a blood oath to protect one another in this world and the next. Nina Simone emerges quietly but audibly in Sheppard’s cosmology to name herself via two figures which evoke the “Four Women”, Saffronia and Peaches. The figures work with and push against their respective biographies from the classic song, creating a dynamic interruption, a kind of visual remix of these female archetypes. If any figure in the diaspora embodies Dark Bodies, Bright Crest, Nina Simone certainly does. Simone gave so much of herself to the public and still she remains, rightfully, much an enigma.

Dark Bodies, Bright Crest is a love story. Cultivating and bestowing the power to love through the generations — the manifestation of a people’s will to survive. In the Bakongo cosmology, the righteous never die, only transform. The return comes through our bodies, through our children, and also in nature — in the power and stillness of the waters. The power of creation, that is our inheritance. The one thing passed on that racism and colonialism has never captured. Through the act of creation, we learn that love is as much autonomy as it is camaraderie. The paintings in this show function much the same way. As much as they share, there is much kept for the viewer to parse. Space is left for pure wonder provided by the consistent use of black as a color. The paintings presented by Sheppard in Dark Bodies, Bright Crest are closely drawn and nuanced portraits, still the subjects keep their secrets. Secrets to be revealed only as they wish. We learn, also on this journey around the sun, that love is freedom. With this new show Ferrari Sheppard encourages his people to keep their heads up and continue walking toward it.

* Spiral was a collective of Black artists such as Romare Bearden, Charles Alston and Norman Lewis. Working in abstraction, the group was active from 1963-1966.