The First Sweet Music,

Curated by Rich Blint

Hanes Art Center, John and June Allcott Galery

115 S. Columbia St., Chapel Hill, NC 27514 United States

Till December 12

Still from Reifying Desire 6, 2014.

About:

Exhibition featuring the work of Lonnie Holley, Diedra Harris Kelley, Jacolby Satterwhite, Jayson Keeling and David Hammons

“Then of a sudden up from the darkness came music. It was human music, but of a wildness and a weirdness that startled the boy as it fluttered and danced across the dull red waters of the swamp. He hesitated, then impelled by some strange power, left the highway and slipped into the forest of the swamp, shrinking, yet following the song hungrily and half forgetting his fear. A harsher, shriller note struck in as of many and ruder voices; but above it flew the first sweet music, birdlike, abandoned, and the boy crept closer.”

W.E.B. Dubois, The Quest for the Silver Fleece (1911)

Under the press of enduring asymmetrical arrangements in global life, visual representations of black Atlantic experience in contemporary art have been preoccupied with scenes of historical slight and modern re-castings of the brutal encounter of subjects throughout the diaspora with the habits of power ordering Western society. Through fantastical re-stagings, strategies of inversion, to expressions of radical self-fashioning and other aesthetic conceits, black artists of the New World south have embraced the convention of “imaging back” to empire—a mode of visual address that has largely proven fertile expressive ground. The First Sweet Music, an exhibition of five cross-generational artists working in photography, painting, sculpture, and video, offers flashes of the “black ecstatic” as another way into this fraught and dense visual terrain, presenting works as a way of orienting the viewer’s gaze to the beauty, grace, and true drama that propels and sustains the heroic activity of human living under the vulgarity of protracted subjugation. Echoing Toni Morrison’s invitation in the opening pages of her novel Sula to the insurance collector descending on a struggling community of the newly free, the exhibition is a metaphorical injunction to “stand in the back of The Greater Saint Matthews Church and let the tenor’s voice dress [you] in silk” in order to see and get “closer” to the higher (or lower) “birdlike” frequencies resonant with the forces that are much of the substance of black survival.

Lonnie Holley’s Gabriel’s Horn (2011) is such a heralding. Thoughtfully mixed in media, this sculpture of found and seemingly disparate objects utilizes the biblical and almost didactic clarity of the horn that crowns it to underscore the need to disturb the slumber in American life concerning the arrested and dangerous state of our democratic project.

David Hammons’ untitled sculpture of Venetian blinds (circa 1986) answers this call across time, space, and form in his dramatically elegant and emotionally incisive re-purposing of this everyday material signifying sight and blindness in a time of desperate urban neglect punctuated by crime, drug abuse, and the overall dispiriting loss of human life and energy.

Diedra Harris-Kelley’s remarkably successful paintings are studies in abstract and figurative rapture. Depicting the artist laboring with the imaginative in her studio (haunted and aided by “demons” and ancestors), and an open-mouthed, wide-eyed figure with horns for hair, these works startle with a mature interiority.

Diedra Harris-Kelley’s remarkably successful paintings are studies in abstract and figurative rapture. Depicting the artist laboring with the imaginative in her studio (haunted and aided by “demons” and ancestors), and an open-mouthed, wide-eyed figure with horns for hair, these works startle with a mature interiority.

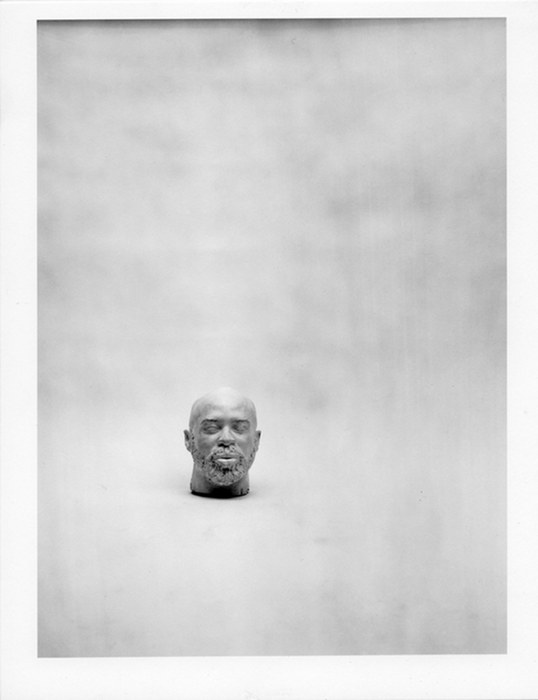

Through his photographs, Jayson Keeling pairs well with Harris-Kelley. Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head (Whisper) (2012), an archival inkjet pigment print of a cast of the artist’s head produced by John Ahearn, is a contemporary riff on the 1853 short story by the Belgian painter, Antonie Wertz, which details the slow, painful death of a beheaded man. Keeling’s appropriated self-portrait contemporizes Wertz’s critique of the rise of capital punishment, relating it to a severed black body politic represented here not simply as the dead and gone, but the quietly powerful, with light radiating from the top of the head and those blinding eyes—to say nothing of the purse of the mouth and spiritual quality of the whisper.

Through his photographs, Jayson Keeling pairs well with Harris-Kelley. Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head (Whisper) (2012), an archival inkjet pigment print of a cast of the artist’s head produced by John Ahearn, is a contemporary riff on the 1853 short story by the Belgian painter, Antonie Wertz, which details the slow, painful death of a beheaded man. Keeling’s appropriated self-portrait contemporizes Wertz’s critique of the rise of capital punishment, relating it to a severed black body politic represented here not simply as the dead and gone, but the quietly powerful, with light radiating from the top of the head and those blinding eyes—to say nothing of the purse of the mouth and spiritual quality of the whisper.

Jacolby Satterwhite’s Reifying Desire 6 (2014) once again extends the artist’s studied pursuit of what he identifies as infinite visual possibility. For him, “visual restraint lies within my body of archives ranging from collected movements by myself and other performers, my mother’s drawings…Merging them together into a dense crystal of information results in the reification of process, a concrete time-based visual system bleeding formal, philosophical, and political ideas”. Like the boy in Dubois’ century-year-old novel, these artists are not fearful of the more dissonant notes that attend corporeal “blackness” and seek to draw closer to a visual vocabulary that renders the existentiality, the “inside thing” of life down here below legible and endlessly seductive.

Jacolby Satterwhite’s Reifying Desire 6 (2014) once again extends the artist’s studied pursuit of what he identifies as infinite visual possibility. For him, “visual restraint lies within my body of archives ranging from collected movements by myself and other performers, my mother’s drawings…Merging them together into a dense crystal of information results in the reification of process, a concrete time-based visual system bleeding formal, philosophical, and political ideas”. Like the boy in Dubois’ century-year-old novel, these artists are not fearful of the more dissonant notes that attend corporeal “blackness” and seek to draw closer to a visual vocabulary that renders the existentiality, the “inside thing” of life down here below legible and endlessly seductive.