‘From the Vault’ entailed that we had to go into the storage spaces of both Fort Hare and Stellenbosch Universities to unearth these collections which have accumulated so much history as an attempt to bring them into the light. We were not so much interested in the grand narrative nor the well-known artists, but we aimed to reveal histories that have been silenced or hidden by remaining in the vault. We also aimed to identify gaps in these histories. We are also aware that in exposing the silenced, we were silencing others too.

Ticha Muvhuti interviews the curators of From the Vault. part of the Stellenbosch Triennale, South Africa

Sunset Over Camel, Richard Mzamane Mabaso-1950, Fort Hare University Art Collection

Stellenbosch Triennale’s From the Vault exhibition

An Interview with curators Gcotyelwa Mashiqa and Mike Tigere Mavura

From the Vault unveiled selected works of modern artists from the art collections of Stellenbosch University and the University of Fort Hare, two institutions which were ideologically and historically placed at the opposite ends of South Africa’s political divide at the height of apartheid, a legacy that continues to shape their outlook to this day. The exhibition, which combined the modernist works and brought them into current dialogue and imagined the future, was curated by Gcotyelwa Mashiqa and Dr. Mike Tigere Mavura. Occupying two floors of the imposing Stellenbosch University Museum building, the show was an integral part of the Stellenbosch Triennale running from the 11th February to the 30th April 2020. In this conversation Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti asks the curators about various aspects of the show.

Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti (BTM): Could you frame the exhibition in terms of its title?

Gcotyelwa Mashiqa (GM): ‘From the Vault’ entailed that we had to go into the storage spaces of both Fort Hare and Stellenbosch Universities to unearth these collections which have accumulated so much history as an attempt to bring them into the light. We were not so much interested in the grand narrative nor the well-known artists, but we aimed to reveal histories that have been silenced or hidden by remaining in the vault. We also aimed to identify gaps in these histories. We are also aware that in exposing the silenced, we were silencing others too.

Mike Tigere Mavura (MTM): The exhibition fitted within the Triennale framework of past, present and future. ‘From the Vault’ was from the ‘past’ if you like. The main Curator’s Exhibition was ‘present’ and ‘On the Cusp’ spoke to the ‘future.’ The title ‘From the Vault’ came from the act of looking into the vaults of Stellenbosch University and Fort Hare University’s art collections and curating an exhibition that brought these collections into dialogue.

Gcotyelwa Mashiqa and Mike Tigere Mavura. Image courtesy of Gcotyelwa Mashiqa

BTM: These collections came from two old universities in the history of South Africa. Some of the work was collected during the years of apartheid. Would you say you noticed something problematic about the collections?

MTM: To be honest that was not our focus. There were a lot of practical things to consider in curating the show. Where does one begin when curating an exhibition from the art collections of two of South Africa’s oldest universities with long standing parallel histories and ideological stances. The art collections are what they are. The biggest problem was how to make these two art collections be in captivating engagement across four exhibition rooms.

GM: All archives have problematics by nature. I had this understanding that the archive is complete; it is true; it cannot be deceiving; it cannot misinform or silence. That is the way archival institutions have been presented. The main problem is in the acquisition of these archives. But we are all aware of the institutional histories, and the links to the apartheid era. Therefore, each collection has certain ideological inclinations. On one hand Fort Hare tried to advance the African nationalist ideology, and Stellenbosch the Afrikaner one. These ideologies inform, influence and determine the acquisition strategies and collections policies. However, ‘From the Vault’ was not focused on those problematics. We were interested in the similarities, rather than highlighting differences.

Image courtesy of Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti

BTM: A collection reflects the vision of the collector. What’s your take from these collections, are there consistencies and obvious biases?

GM: Of course, collections are made of people’s biases and prejudices. They are also a reflection of the institution’s principles. Collectors decide what to leave out and that which can be included. Anything that is done by an individual is subjective.

MTM: Our approach was to deliberately mute the past and re-imagine the collections themselves anew. We were asking ourselves different questions. We were interested in ways of hanging that would form a ‘collection’ drawn from two distinct collections. We were asking on ‘the vault’ being the archive of the old and ‘social media’ being the archive of the now and how could the exhibition and its context be activated and translatable to the new social media archive in interesting ways. For example, the works in the exhibition are hung in clusters and if you take a picture of the clusters with a cell-phone the clustered paintings appear like sculptures on a wall which take different shapes and forms as you tilt your cell-phone and look at them from different angles. You could only experience this aspect of the exhibition if you take pictures with a cell phone.

Image courtesy of Trevor Chomumwe

BTM: Were there intersecting themes and ideologies?

GM: Ideologies mostly apply to the institution, not the work per se. African versus Afrikaner ideologies, institutions desiring to preserve and promote those legacies. So, there was that similar ideology of wanting to further their own cultures. Interestingly, even though the Stellenbosch collection tries to promote Eurocentric values – surrealism, expressionism, cubism, and so on, there are still intersecting themes in the work. Notably, the Fort Hare Collection is from the nineteenth century, and the Stellenbosch one stretches into an earlier period, and therefore some of the works are much older.

MTM: I think there were, some more obvious than others. But I am weary of the gap between themes spoken of and themes and ideologies visually experienced. It would be of great interest to me to find out from those who have engaged with the exhibition what kind of themes they thought the exhibition conveyed.

Image courtesy of Trevor Chomumwe

BTM: The collections are from two universities with different pasts. Is there much difference in the work, maybe in terms of tastes or preferences?

GM: Artists from Stellenbosch had a proper European education. Not that I intend to undermine the artists from Rorke’s Drift, the Community Arts Project and Polly Street Art Centre, but these were run by non-governmental organizations, and their certification had less weight compared to those coming from Michaelis School of Fine Arts for instance. But interestingly a similar style, that of abstract expressionism and realism, dominates their work. The artists at Rorke’s Drift were also influenced by what those from Michaelis were doing. So, there is not much of a difference, just that they were separated because of the segregationist laws. Geographically, they were coming from different places, but there is something universal about their work.

MTM: Our general approach was to deliberately blur looking the two collections as distinct and look at what I would term ‘commonalities.’ The following quote by the late Fort Hare graduate, artist and intellectual Selby Mvusi, “The past does not matter in a practice where the problem to be resolved, the commitment to be recognised and the question to be answered is: What is Our Time?” was floating in the framework of our thinking, “What is Our Time”? We wanted new tools of thinking about the collections, new reference points so we sort of ‘muted’ the straight way of looking at the collections: different universities, different ideologies (Afrikaner nationalism vs African nationalism), different geographies (Alice, Eastern Cape vs `Stellenbosch, Western Cape), tastes, preferences etc

Image courtesy of Trevor Chomumwe

BTM: There are many universities with art collections in South Africa. What made you settle for these two?

MTM: We settled for them due to the practical matters – of accessibility, time, resources etc.

Image courtesy of Trevor Chomumwe

BTM: What was your curatorial intervention in reworking this archive? Was the attempt to make the work communicate something different or you let it speak for itself?

GM: We looked for works that spoke to us. It was mostly us being directed or guided by the work. We assigned a theme to each space and tried to rationalize how each work could fit within a theme: the ancestral, healing, meditation and so on. Some works were left out because they did not fit into the conversation taking place in a certain space. There was a lot of subtracting and adding or shifting of works as we looked for works that sustained the conversations. We also had to repaint the walls as a literal curatorial intervention.

MTM: The curatorial interventions were many, intentionally and unintentionally. We were intervening in a space, the `Stellenbosch Museum’, we were intervening into both archives and further by putting the two archives in some kind of conversation. Broadly, our curatorial intervention was to try to make this archive relevant now, how to make it speak and be situated in the present in terms of aesthetics (presentation), discourse, knowledge production and so on. The approach was to blur the distinctions of ‘this is the Fort Hare Collection’ and ‘this is the Stellenbosch Collection’ and to allow the artworks from both collections to speak to each other, to see how we are with ideas of hybridity, the third space so to speak, to use artworks from both collections to create a dialogue that transcends the past and maps a way for the future. I am glad that speeches by both Vice Chancellors of Stellenbosch and Fort Hare touched and expanded on this point.

A Legend of the Basotho Warrior, Leonard Matsoso, Stellenbosch University Collection

BTM: What’s the relevancy of these collections in terms of the current calls for decolonization in South African institutions and society?

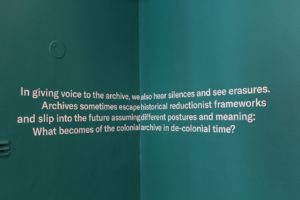

MTM: There was text on one of the walls in the exhibition that read “In giving voice to the archive, we also hear silences and see erasures. Archives sometimes escape historical reductionist frameworks and slip into the future assuming different postures and meaning; What becomes of the colonial archive in de-colonial time?” The exhibition was an attempt to answer to your question in a sense, the whole Stellenbosch Triennale was also an answer.

GM: The Fort Hare Collection is not fixed in a specific time period. The issues the artists were dealing with are still relevant today. Decolonization in South Africa precedes Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall. The fight against apartheid in the 1960s and 1970s was a decolonial project. The fact that these works were created in that era means they have always been part of a decolonial project. They remind us not to think of time in a very linear way when exploring the decolonial project in this country. That apartheid ended in 1994 does not mean we are living in a decolonial era free of any apartheid legacies. There is also this interdimensional element about time characterized by intersects and overlaps. So, the works are as relevant now as they were in the past.

BTM: There seemed to be more work from Fort Hare compared to that from Stellenbosch in the exhibition. Was that a reflection of the curators’ biases, or why was that so?

MTM: There was no mandate or conscious thinking around we were going to use this amount of works from Fort Hare and this amount from Stellenbosch. We just worked according to the curatorial process we had in place. I haven’t really noticed that there seemed to be more work from Fort Hare. That’s interesting.

GM: I would say yes. Personally, I would not curate from a neutral position. Whatever we did with these collections is very subjective. At some point we had disagreements about certain artworks. That’s natural because we are coming from different backgrounds: Mike is coming from philosophy and politics, I am coming from Fine Arts, photography to be specific. We mostly opted for conceptual or abstract work.

BTM: The exhibition was also dominated by male artists. Would you like to say something about female representation or the lack of it?

GM: We did not see all the Fort Hare Collection as we had to deal with that which was shipped to us. There was only Gladys Mgudlandlu. The same applies to the Stellenbosch collection. There is Irma Stern, Helen Mmakgabo Sebidi and a few other names. I guess it is also a reflection of the time the works were made in institutions that mostly trained male artists.

MTM: These are some of the silences and erasures highlighted in the text I referred to earlier, but we can only highlight an historical wrong in an exhibition that looks at art collections from the past, we can intervene and act now so that if you compared black female representation in ‘From the Vault’ with the other programmes of the Triennale such as the Film Festival, The Creative Dialogues, On the Cusp and The Curator’s Exhibition, one could see that strides have been made.

BTM: You have curated work by contemporary artists. Some of the names in this show are well written about in Art History. They are masters. How different was the experience compared to dealing with the current?

GM: There is something overwhelming about working with the work of these modern artists. I could feel their spirit present. I wouldn’t say that element is missing in working with the contemporary, but there is just something about the work of somebody who is no more, there was so much weight in there, the spirit in the work having to come alive. It felt like curating a soul of something, not just an object. There was this overwhelming presence. Mind you the work was made in a certain context, and it re-lives or carries that, even in this day.

-

Gcotyelwa Mashiqa is an independent curator and visual historian based in Cape Town. She is currently completing her M.A. in Museum and Heritage Studies and Visual History at the University of Western Cape. Her research is on social documentary photography in the anti-apartheid archive.

-

Tigere Mike Mavura is an independent curator based in Cape Town. He is also a lecturer and change agent at the Stellenbosch Academy of Design and Photography.

-

Trevor Chomumwe is a content producer based in Cape Town.

-

Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti is a Ph.D. candidate in Art History in the NRF SARChI Chair programme in Geopolitics and the Arts of Africa, Rhodes University.