“Call and Response is a visual remembrance of the way in which the stories and histories of blacks in America have repeatedly been confused, smudged, silenced and fractured by those in power, those who hold the gaze.”

Alexandra Giniger reviews the latest exhibition of Glenn Ligon.

So Black and Blue: Glenn Ligon’s Call and Response at Camden Arts Centre

The systematic oppression of people of color at the hands of America’s law enforcement echoed unrelentingly in my mind, even as I wandered through various art galleries during a recent visit to London. The bright lights and fast pace of Frieze week afforded a somewhat welcome distraction; but, I wondered, when all the art has been sold off the gallery walls, how much of what is consumed actually holds political weight and the promise of remembrance, of change? I needed dialogue; and I found it in an exhibition by Glenn Ligon.

Ligon’s exhibition, I was informed, was “a bit of a trek from the epicenter of Frieze” (zone 2 on the tube, after all!) and to see it only if I found the time. A longtime admirer of his work, I could not resist. Especially when I recognized that his most recent exhibition, Call and Response at Camden Arts Centre, was a visual representation of my political consciousness – and conscience – I knew I had to live this experience.

The artist did not disappoint. Emerging from the frenzied environment of Frieze, I entered Ligon’s world and breathed a sigh of relief. Spread throughout three upstairs galleries, Ligon has been given reign to transform the space. The sanctuary-like rooms were mostly empty, save for the spirits embodied in the heartbeat of neons and in the “voices” on canvas.

“What did I do to be so black and blue?” – Louis Armstrong

At the gallery, viewers first encounter the latest installment of Ligon’s familiar neons. More than a sculpture simply occupying a room, Untitled (Bruise/ Blues) (2014) serves as an installation piece which completely transforms and enlivens the chapel-like space in which it is housed. The words “bruise” and “blues,” which flicker between a dull, muted black, and a bright, electric blue, are hung back-to-back, facing away from each other, as if the two monuments are engaged in duel. At first glance, the neon lights appear to flash concurrently. Closer attention demonstrates, however, that they are instead ever-so-slightly unsynchronized, as if signifying a struggle between these connected words against meeting, even though they are forced to do so.

That Bruise/ Blues visually depicts a Freudian slip of the tongue is no accident. Ligon borrowed these words from the testimony of Daniel Hamm, an innocent teen rounded up with five other Harlem residents during the April 17, 1964 Harlem Riots. Dubbed The Harlem Six, Hamm and the others were subjected to agonizing racism and police brutality, and were eventually imprisoned for crimes they had not committed. James Baldwin describes this tragically commonplace travesty best:

On April 17, some school children overturned a fruit stand in Harlem. This would have been a mere childish prank if the children had been white—had been, that is, the children of that portion of the citizenry for whom the police work and who have the power to control the police. But these children were black, and the police chased them and beat them and took out their guns… No one in Harlem will ever believe that The Harlem Six are guilty—God knows their guilt has certainly not been proved. Harlem knows, though, that they have been abused and possibly destroyed, and Harlem knows why.(1)

During his testimony, Hamm described having to make his beaten and bruised body bleed in order to receive medical attention: “I had to, like, open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them.” What Hamm actually says, however, is “blues blood,” instead of “bruise blood,” which serves as inspiration for Ligon’s work. Walking around the gallery space while physically weaving in between the words of Hamm, one has the palpable sensation of his spirit brought to life in the room. Though the words remain tacit, the repetitive flashing lights become an almost audible heartbeat, transporting Hamm’s legacy and message into the present.

My only sin is in my skin/ What did I do to be so black and blue. Louis Armstrong.

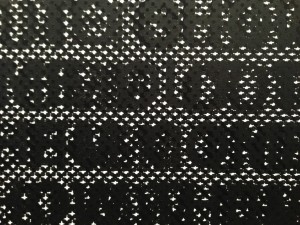

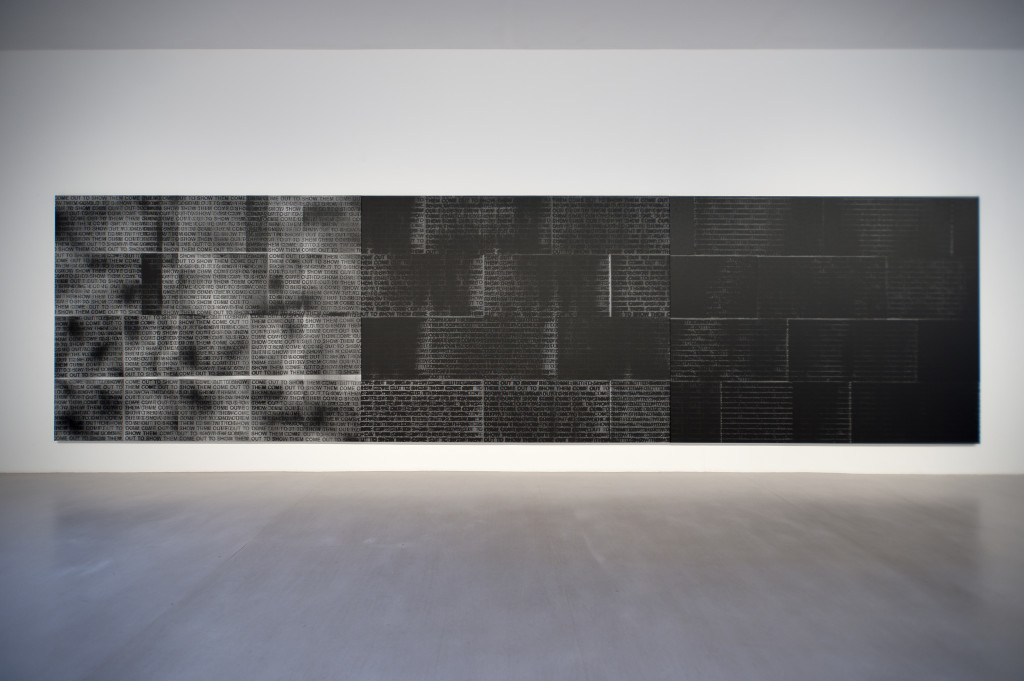

“I had to, like, open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them.” These powerful words from Daniel Hamm’s testimony were previously appropriated by minimalist composer Steve Reich in his 1966 sound piece, Come Out, created in protest of the unfair treatment and trial of The Harlem Six. The thirteen-minute sound piece is a repetition of this line, at first playing the words audibly, and then overlapping them to the point where the sound becomes chaotic abstraction. Channeling both Hamm and Reich, Ligon constructed visual representations of this abstract, chaotic form in his 2014 silkscreens. In Come Out #4 and Come Out #5, the words, “come out to show them” are printed repeatedly across a wide array of canvases.

From a distance, the words appear so abstracted that the viewer experiences the illusion of gazing upon pulsating, multidimensional waves of light and shadow. A closer examination of the canvases reveals these seemingly abstract patterns to be, in fact, quite intentional repetition and layering of Hamm’s speech. Limiting the print to black ink, Ligon endows his canvases with the appearance of smudged newsprint or burned records. The works become transformed into visual reminders of the muddled histories, of the destroyed and discarded testimonies surrounding the systematically unfair treatment of Hamm and The Harlem Six. As I stood before the power of Ligon’s emotionally effusive works of art, the realization that the story of Hamm and The Harlem Six remains overwhelmingly relevant today, in 2014, became poignant. Ligon’s layered collections of words are like the pools of clotted blood bruising Hamm’s body – again, projecting his legacy into the very real and present threats to the black bodies of America. And everyone “knows why.”

They laugh at you and scorn you too/ What did I do to be so black and blue, Louis Armstrong.

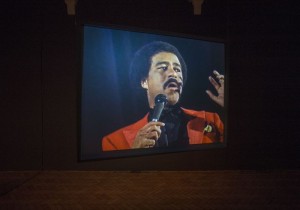

In the final gallery of Camden Arts Centre, we encounter Live (2014), a multi-tiered, seven-screen video piece in which Ligon has extracted fragments of Richard Pryor’s 1982 stand-up show, Live on the Sunset Strip. By eliminating sound in this work, Ligon renders funny man Pryor something of a pastor at work. With his intense gesture alone, Pyror commands the viewer’s attention; yet his message is silenced, fractured, and split, leaving arbitrary interpretation up to those who gaze upon him. Though Pryor has no words in Live, Ligon provides both text and context in the form of the other works presented in the exhibition.

Call and Response is a visual remembrance of the way in which the stories and histories of blacks in America have repeatedly been confused, smudged, silenced and fractured by those in power, those who hold the gaze. By transforming his audience into gazers, who now inhabit positions of power, Ligon has called upon us to “come out” – to clarify our stories, to protect our lives, and to effect meaningful change. How we respond to this experience, Ligon leaves up to us.

Glenn Ligon: Call and Response is on view at Camden Arts Centre in London through January 11, 2015.

(1) Quote from article of James Baldwin: A Report from Occupied Territory, 1966, The Nation.