I’m really fascinated by the fact that we think that history is truth, but it is not. History is what someone said was the truth at the time. Art is not the truth, but art can be truth; it can also be the fantasy of the truth, an exaggeration of the truth, or it could be simply beautiful or simply horrific. (…) The work that I make is part of English history, is not just of black history. It is reciprocal. Histories are entwined.

The artist Godfried Donkor – born in Ghana, London based – in conversation with Raquel Villar-Pérez

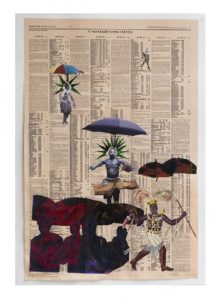

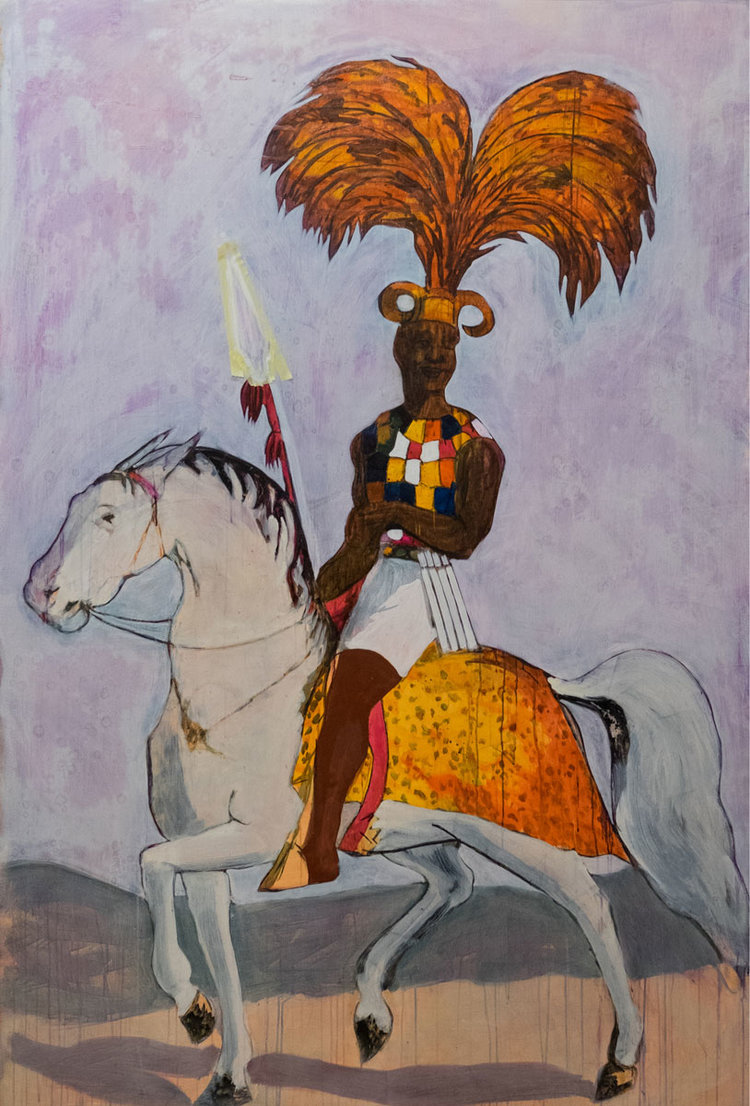

The First Day of the Yam Custom, 1817, 2017. Source: Gallery 1957

Godfried Donkor

A painter who happens to make collages

A new contemporary ‘African’ art exhibition opened at MAXXI, the National Museum of Art of the XXI century, in Rome early this summer. African Metropolis. An imaginary city aims to ‘highlights the beauty and the contradictions of the cities and the world of today’. Another exhibition to add to the roaster of, exclusively ‘African’ art exhibitions that have been happening for the past years, and once more, Simon Njami is the curator of the project.

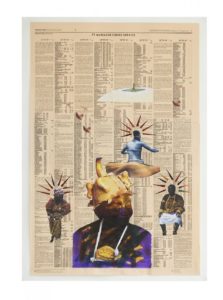

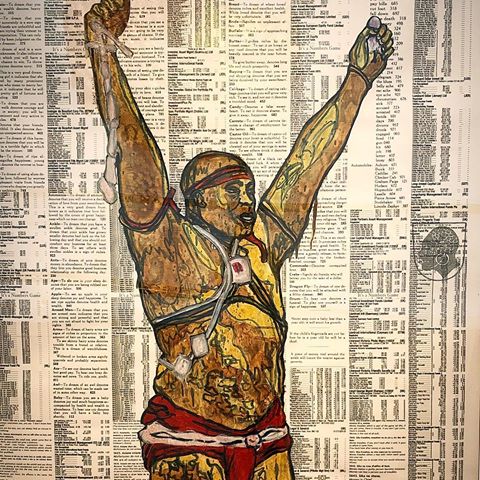

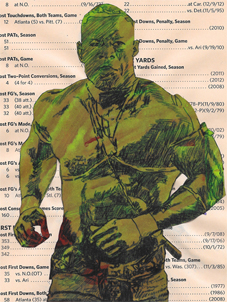

Olympians, 2018. Source: #maxxi Instagram

Having significantly been exposed to contemporary ‘African’ art for the past five years, the narrative of this type of shows does not interest me much anymore. However, there are two things of importance with occasion of African Metropolis: first, the art exhibited itself. Simon Njami always surrounds himself by his, undoubtedly virtuous, quadrille of artists, and it is always worth to see their work individually; and second, the fact that the exhibition takes place in a society well known by its continuous racist attacks. Indeed, only a few days after the opening of African Metropolis in Rome, the Italian athlete of Nigerian parents, Daisy Osakue was attacked in Turin.

I have not had the opportunity of visiting the exhibition in Rome. Yet, in the middle of the arrangements for his forthcoming participation in the Kampala Biennale and 1:54 London, I met Godfried Donkor, one of the exhibited artists at African Metropolis, to talk about Rome, art, and racism.

I agreed to meet Godfried outside Brixton station in South London, the neighbourhood where I used to live over a year ago. I found him outside the station, dressing sport gear and with an amicable smile. We head off to the Nero café on the top floor of the Morleys department store. Opened in 1880 under the name of Morley & Lanceley, it remains as one of the few places that have survived the gentrification and the consequent hypsteristisation process of the area. Godfried’s studio, unfortunately or fortunately as he states, has not.

Raquel Villar-Pérez: Tell me about your journey as an artist, when did it start? When and why was the turning point in your career as an artist?

Godfried Donkor: I think we all begin in Art school, then you think of to be an artists but you don’t really know what that means, because, in Art School they don’t really teach you how to become an artist.

In my case, when I left the art school I went to Spain, I stayed in Barcelona for two years, and then I came back to the UK and worked in various places in the arts. I had a studio shared with my friends. There were many of us around working and producing art, even big names such as Damien Hirst, but he was just like us, not making any money. We never knew the notion of being a functioning artist becoming famous and able to survive of your work.

Then I decided to do my MA at SOAS University of London because I was particularly interested on the discourse of African culture and African contemporary art. I wanted to know more about it at the same time I was still practising as an artist. My experience at SOAS gave me what I needed as part of my research. For me, the first transformation as an artist was in 1997 when I worked for the Durban Biennale in South Africa. It gave me a massive experience and exposure to international artists. Then in 1998 I participated for the first time in Dak’Art Biennale; that was my first big exhibition. Then I decided I wasn’t going to do anything else: I was just going to make my art, whether I had money or not.

Raquel: There are many of us, slightly younger than you that are in the midst of creating our careers within the not-so-easy art world. You are a model of searching yourself and re-defining yourself. How was this process?

Godfried: It is a process that I think I’m still going through. I don’t think one ever stops. It fascinates me the notion that you can spend your whole lifetime seeking to know about your work. Back in the day I would read about Matisse. Matisse was 80 and he couldn’t stand up to paint, he was lying down and painting with a stick… then he said: now I know how to paint. At 80!! To us, he was doing a masterpiece that we all think was brilliant! However, he only acknowledged mastering the technique 50 years later.

When you finish Art School, you don’t know anything about your work. When you are in your mid-career you don’t know anything about your work. Then at the end of your career, then you start to know, if you are lucky. So I’m always discovering myself, and every project that I do is a new experience I’ve never done so I’m learning something.

Raquel: Your work makes use of numerous historical references, as well as iconic characters. Would you say that your work functions as mean for re-creating black history and re-telling it?

Godfried: I think as an artist, I re-create history full stop. Not just black history because I don’t think black history is separate from the rest’s history. The work that I make is part of English history, is not just of black history. It is reciprocal. Histories are entwined.

Olympians, 2017. Source: Deskgram

Raquel: But there still are power relations deciding how the history has been told, and I think these need to be taken into account. I can recall the project that you made for the 1957 Gallery in Accra last year. The show was inspired by an image part of Thomas Bowdich’s Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee book that you came across with whilst studying at SOAS. That was the perspective of a white British ‘explorer’. How would it have been represented if a Ghanaian person had been given the chance of illustrating the festival for later generations? How would it had been told?

Godfried: I saw this image ‘The First Day of the Yam Custom’ when I was at SOAS in 1995, and ever since I had wanted to re-create the image. In my head, I had re-created and re-created, and only in 2017 I managed to work on it. The image was published first time in 1819. I was recreating it 200 years after.

Yes, we need to take into account the politics of who tells the story. As an artist, I know I can re-imagine stories if I want, and it is up to me how do I re-imagine it, and by re-imagining it, I bring something new into it. I’ve taken it out of the context of 200 years ago. 200 years after the original, the whole layout and meaning of the image changes, and that’s fascinates me. The fact that art that we are making now, will change in context in 20-30-50 years from now. Art changes its context all the time.

The First Day of the Yam Custom, 1817 (detail), 2017. Source: Gallery 1957

Raquel: When did you start producing collages and what are its potentialities as your visual language compared to any other? Are the backgrounds of your collages carefully chosen?

Godfried: I trained as a painter, and I’m still training as a painter. I’m still learning to paint. Paint is my medium. I started making collage at Art School, but it is a technique that I develop from my scrapbooks, when I was in Art School. Initially, I went to Art School to be a fashion designer, so I think I have these fashion aesthetics. I started using collage as studies for my paintings. At that time, I was doing collages as drawings, not as artworks; it was only later that one of my curators friends told me: those are going to the show as well. And that became a new arena for me to explore: photography, collage…

Collage for me is spontaneous, it is very quick to make images with collage, simple formats, simple cut outs, and this helps me build up my narrative, composition, and subject matter. For instance, because the most of the subject matter I use is historical, I use a lot of black and white photography made over 100 years ago. I can cut that out and put in the scene of a photograph that I’ve taken today of Brixton station. I quickly can blend 1905 with 2018, to talk about time, change in fashion, etc. I’ve noticed that now when I look to modern films, collage is basically what visual effects are. The most basic principles of collage are being used at a higher level to make blockbuster films. I find it fascinating.

Raquel: What are your sources for inspiration?

Godfried: Everything, hehehe… but mostly historical, and I like it because it is past, indeed the further back it’s gone the better I like it, because that means that we have actually forgotten the context of where it was taken or what does it mean.

I’m really fascinated by the fact that we think that history is truth, but it is not. History is what someone said was the truth at the time. Art is not the truth, but art can be truth; it can also be the fantasy of the truth, an exaggeration of the truth, o it could be simply beautiful or simply horrific. But I love historical material. I love ideas of the future, but I can use historical material to re-create new images.

I think this is the re-occurring theme in my work that is the notion that history can be used over an over again to tell many different stories.

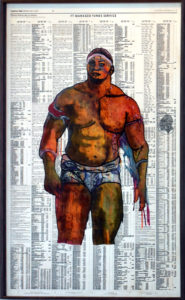

Ashanti War Captain I, 2017. Source: Gallery 1957

Raquel: Elsewhere you stated that you are ‘always working at trying to overcome my frustration… I’m enjoying the process much more’. Can you please span on the notion of your frustration?

Godfried: My frustration with painting; my frustration of not being able to paint what I want. I’m searching for a formulation of a language for painting. I’m not looking for perfection, because once you get there, there is anywhere else where to go. I look for imperfection to make corrections, but my frustration, which I’m beginning to accept, is my inability to paint. However I enjoy the challenge of the frustration of how to learn doing my work.

Anokye’s Dance, 2017

Raquel: I met a well-known Spanish curator friend of mine a few days ago during my holiday break, and we spoke about the notion of identity. She pointed that nowadays it is difficult to have an ‘identity’ but we rather face ‘identity processes’ and therefore, identity is ever-changing. That reminds me of how in other interviews you’ve spoken of how your practice in Ghana is influenced by your experience in London and the other way around. Not only that, but you have another studio in South Africa, and if I’m not mistaken, you dream of opening studios in the Caribbean, and Senegal. You greatly embody what is considered a ‘transnational artist’, and therefore exposed continuously to these ‘identity processes’ that my friend and I talked about. Could you delve into this idea?

Godfried: In Senegal, I built a studio for eight weeks, where I worked on the works exhibited at Dak’Art Biennale and for MAXXI. I was given a residency at RAW Material Company, so I worked there.

I don’t really need to build a structure, I can just grab my pencils, and materials and go anywhere and make arts. As a matter of fact, wherever I make my studio is not important, what is important is the work I make. Sometimes I will be in the Caribbean making work about the UK or Ghana or the other way round. It’s like a kind of nomadic studio-style, but it came about when I started loosing my studios in London in 2006. With the urban re-planning, they started closing down the arches under Brixton station and I couldn’t have a space where all my material was. Then I pondered whether I was going to limit myself to London, but realised I could be sending material elsewhere and go and work there for a period of time.

What is really fascinating for me is how we as human beings combine, and have merges. For instance, the fact that I live in Brixton and you’ve live in Brixton brings us together with some sort of neighbourhood identity, or English language is used in the Caribbean but you can tell that the language is used along with African intonations or African words, and that’s something that they call ‘broken English’ which is patois. These are all mixes of cultures and mixes of peoples, as opposed to the idea of purity, or the pure human being. At the end of the day, this doesn’t exist. The reality is that everything is mixed.

Olympians, 2018. (Installation view.) Courtesy of the artist.

Raquel: Tell me about the works exhibited at African Metropolis at MAXXI in Rome

Godfried: The works exhibited at MAXXI are part of a larger series of 18 artworks so far. In particular, the ones at MAXXI explore the Senegalese culture of wrestling and its history. It is a sport, and is a ritual. I’ve been fascinated by the Senegalese wrestling for about 20 years, since I first went to Dakar. One of the things that attracts me the most, is the combination of two elements: the fact that these are sports people who are physically fit, and how spiritual and superstitious they are; indeed, they have a spiritual leader that makes for them like a potion to make them even stronger. They believe that their skill is not enough, they need something else, and guidance from God that gives them the extra thing they need to win. The whole event is about performance, is about spirituality, is about dance, about music, is not just about wrestling, and that is what I find fascinating. It talks about the rituality of human interaction.

Raquel: The current exhibition at MAXXI in Rome African Metropolis curated by Simon Njami, contains the same discourse as Afriques Capitales, shown in Paris the last year. You participated in both of them, what makes them different?

Godfried: Well, I’ve talked to Simon beforehand and I think I understand what he is trying to present as a curator and historian. He is trying to bring contemporary African visual aesthetics to certain European cities. Paris may seem like the obvious place, there are so many Africans in Paris, and it is assumed that it is known what is happening in Africa in terms of arts, but I don’t know if this is true, certainly they don’t know in Rome. What was interesting for me was the challenge of making new work that would present my visual aesthetics to these places. The works shown in Paris were made two years ago, and the ones made for Rome, were a continuum of the project. The ones for Rome were made along with the ones presented at the Dak’Art Biennale this year.

Olympians, 2017. Source: France Fine Art

Raquel: Oh, so the series has been actually shown in Europe in Africa. How do you think the different audiences have received the works in the different countries?

Godfried: This I can’t say, because I need other people to tell me that. I think in the Senegalese context, I believe, that because the sport of wrestling is so popular, people would have seen it in a more pop art context, like someone has made popular work, almost like I made superheroes. Whilst Europe I would imagine, would look at it as a kind of exotic art, something that comes from Africa.

Raquel: What’s your take in these exhibitions, which only show artists of Africa or of African descent? How do you feel about the label/category?

Godfried: I think these exhibitions contribute towards de-exoticising African arts. I’m not too preoccupied with it. I don’t look for exhibitions; I work with curators or historians that invite me to do certain things and if like their practise I will do it. I’m not sure what this will mean for the history of art in the long run though.

Raquel: I wanted to touch upon the recent events that happened in Italy involving racist acts towards the Italian athlete Daisy Osawkue attacked on the 30th July. Just after the opening of African Metropolis.

Godfried: It is very interesting the situation in Italy. I was an artist resident in the Bellagio Centre in Milan. Whilst I was there, I saw thousands of African kids who were part of a refugee programme. Most of them were in the streets, jobless, some were begging… you realise that there is an issue there. In fact, my proposal for the residency had to do with historical movement of people in Europe. I was working on images of medieval coat of arms that had Africans on it, and they are from Europe. So I was doing a study of these guys, you see them in the squares in Milan, in the train stations, and eventually you see them outside clubs as security guards or in department stores. This is a process of transition, a process of movement of people. Europe has always had this issue, banishing people from Europe, or Europeans going elsewhere. The work I’m doing with the coat of arms, for me is a visual recreation of going back to 1400 and finding out why there were Africans within Europeans’ coat of arms, what is the link, and look at what is happening now and why is that?

Olympians, 2017. Source: Nofi

Raquel: That’s interesting because one of the reasons why I moved to London was because I found Spain quite racist

Godfried: Well, I lived in Barcelona for two years and I encountered certainly that, but I’ve been in the UK for 48 years and I have encountered a lot of racism here too. I think the idea of racism is a very archaic emotion for me; somebody doesn’t look like you so you hate him or her, this is very basic. But that starts to change as soon as you know the person, or their culture. I think the situation in the world will change, it will take a very long time, but it will change.

Raquel: Do you have a dream project that you haven’t been able to realise yet?

Godfried: I think it is this project I’ve been working on since 2008, and I would like to realise that one day, but is no way near to its full potential, it talks about this idea of movement of people into Europe.