“His latest exhibition, he says, is inspired by childhood memories. Perhaps by diving into his early life, his beginnings, he hopes to better understand his vantage point. Although highly unlikely, if we are lucky, we might get a quote or two on what he has discovered about himself. Fortunately for Gor, even though he is so headstrong and very efficient in fleeing from interviews, his work in most instances is provocative, tells its own story, and can in fact survive and thrive without his presence.”

With these words Zihan Kassam concludes her essay on Kenyan artist Gor Soudan.

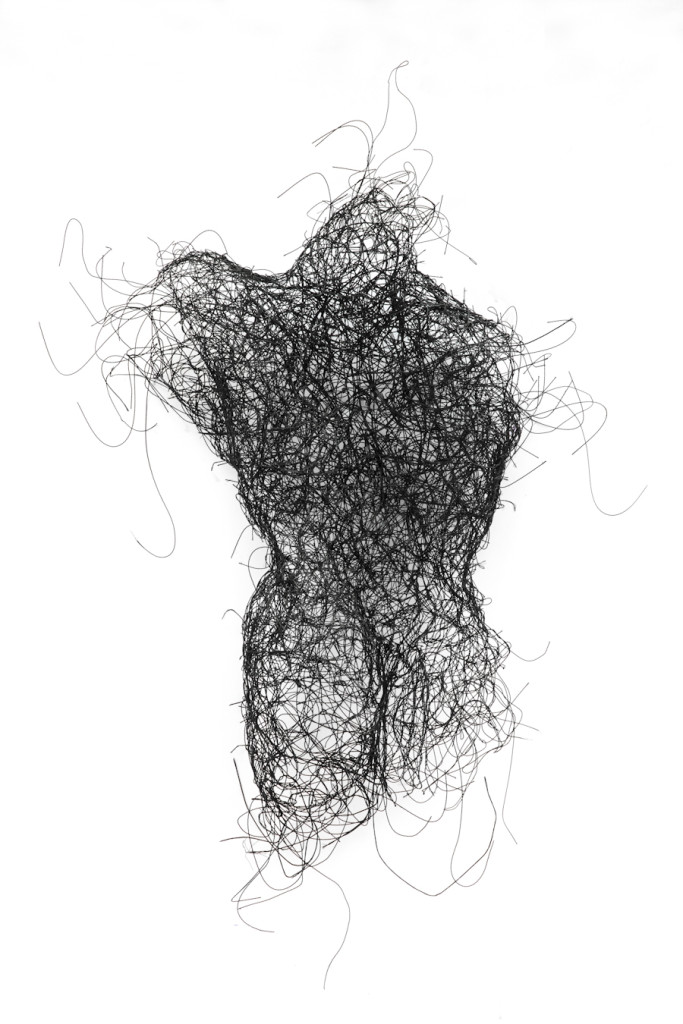

From the Resurrection Series, 2013.

The Preserved Interior

Two Worlds Apart: Gor Soudan exhibits at ‘Red Hill Art Gallery’, Kenya

Do artists really need to talk about their artwork or does art speak for itself? An artist might be cordial enough to explain what his or her latest series is about, and while it is certainly valuable to have the artist’s perspective; audiences will also have their own, personal interpretations.

Artists who take the time to talk about explicit messages in their work might still fail to find resonance with the audience, while other artists, who quietly ruminate on canvas, possibly unaware of their own impetus, can influence his audience in a visceral way. It is always refreshing when an artist can support his work by articulating his thoughts, but art should be able to move you without an accompanying narrative.

Few artists seem to make this point better than Kenyan Gor Soudan, notorious for rousing his audience with poignant creations and then hitting the road before anyone dares to engage him in the arduous process of feeding an imagination-starved audience with token words that will only dissect, and detract from, his abstract creations.

Except when he is pressured, Gor runs away from discussions that scrutinize his intentions and from conditions that take his audience away from the raw, intuitive responses he hopes his art will prompt. Dismembering his work into moves and motives robs the viewer of their instincts; of the voices in their head. “I don’t know,” Gor responds brusquely when asked about the meaning of one of the powerful ink drawings he did in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Predictably stubborn, his aversion to questions offers a valid argument: Don’t talk about the art – feel it, know it.

From the Crow Series, 2011.

From the Crow Series, 2011.

Not long after receiving his BA in sociology and philosophy from Egerton University, Gor decided he would communicate some of his ideas using art. The Nairobi-based artist rented a container-studio at the Kuona Trust Centre for Visual Arts in Kenya (Kilimani, Nairobi) where he began making art using unique combinations of local materials. His Crow series caught the eye of many visitor at Kuona. In February 2012 – while still at Kuona – a joint exhibition with popular contemporary artist Paul Onditi (‘Another World is Possible’) at the Alliance Française in Nairobi brought serious attention to his work.

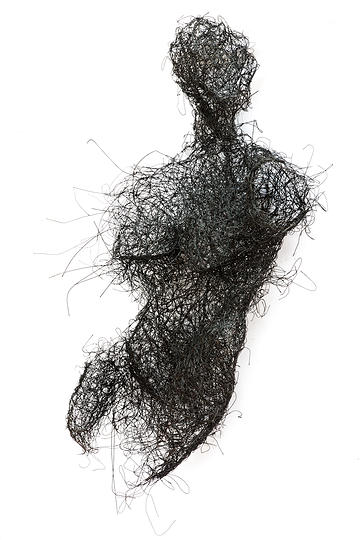

Using old cardboard boxes, garbage bags, empty cigarette packs, acrylics and found objects, Gor has become popular for producing aesthetically captivating works that offer satirical commentary on the socio-political state in Africa. He mocks the corrupt government in Kenya and has even gone as far as to use torn pieces of the new Kenyan constitution as a medium in his work. Gor receives international attention from globe-trotting collectors intrigued by his peculiar world of mutated figures, pensive crows, ominous birds, bristly nests and fatal smokers. Much of his upcoming work is produced in protestwire, a term he coined for the tangled mess of black wire he collected from car tires burnt during the political riots and civil unrest in Kenya.

From the Resurrection Series: The Fire Next Time, Untitled, 2013.

Considered by many to be Gor’s magnum opus is the work ‘Resurrection’ made of protest-wire and railway sleepers from the Kenya-Uganda railway line. Several three dimensional forms were hung together producing an apparition of Christ on the cross. Although none of the parts touched, our brains work to fill in the gaps and construe an iconic image it is familiar with. ‘Resurrection’ was one of 13 protest-wire sculptures exhibited at the Nairobi National Museum at ‘Resurrection: The Fire Next Time’, an exhibition curated by Olutosin Onile-Ere Rotimi, founder of the Iroko Art Consultants (August 2013).

Rising rapidly in the ranks of contemporary East African artists, Gor was invited to travel extensively from February 2014 until the end of last year when he exhibited his artwork for the second time at the 1:54 art fair, an annual contemporary African art fair in London. He began the year with a pop-up exhibition of his latest work in Freetown, Sierra Leone. He then participated in an artist residency at the Arts Initiative Tokyo (AIT) followed by collaboration with American artist Albert Samreth at Yamoto Gendai Gallery in Tokyo. During his time abroad, he produced an ontological study of bubbles and shells, exploring the history of enclosed spaces, domes and ecosystems. At the end of his project, he composed a limited edition book called ‘Bubbles and Shells, Protest Wire 2014.’

Bubbles and Shells VI, 2014.

Bubbles and Shells VI, 2014.

His ‘Bubbles and Shells’ series included six protest-wires, egg-shaped ‘nests’ that became extremely popular. The first two are in the Backers Foundation Collection at the Hara Museum, Tokyo, Japan. ‘Bubbles & Shells 3’, the third of the six sculptures, was sold for a whopping Ksh645, 700 ($7,014) at 2014 Circle Art Auction in Nairobi. From the same series came a handful of works on paper, two of which were acquired by the Yuan Museum in Tokyo and the Backers Foundation Collection. The third work on paper ‘Stirring Attractions’ also sold at the 2014 Circle Auction, for an impressive Ksh352,200 ($3,880).

Running from November 16, 2014 to January 17, 2015 Gor Soudan’s ‘Two Worlds Apart’ exhibition at Nairobi’s Red Hill Gallery is an exhibition of the artwork he produced in Japan and Sierra Leone. Except for the pair of striking figurative sculptures in protest-wire, hanging at the center of the gallery – ‘Eating I’ and ‘Eating II’ (borrowed from independent art dealer Lavinia Calza). They reveal two beautiful, nebulous forms, comprising head and torso, mystifyingly emotive in their lack of detail and expression. The remaining 35 works bare Gor’s opaque palette and his minimalism, while exposing new techniques and subject matter.

Eating I, 2013.

His ‘Cactus Studies’ are created in his familiar combination of black, grey and white. Gor has an interesting way of demarcating the delicate thorns of the cacti – by etching at the darker backdrop of charcoal to reveal the naked white of the paper underneath. Images of his nests or bubbles are created using a similar technique and palette. Using ink and acrylic on paper, Gor also produced a handful of paintings comprising a single or couple of neon circles (in either luminous green or orange), with what looks like DNA or atomic particles (the ‘stuff of life’, if you will) stringing out of these spheres. The images are relatively tedious; ambiguous in an uninspiring way, and certainly not his most exciting work.

Both magnetic and thought-provoking however, are Gor’s figurative ink drawings from Sierra Leone, depicting the nude male form under different conditions and circumstances. An untitled work (Gor’s artwork is mostly untitled) that most people will relate to depicts a man weighed down by a plate on his head that is full of obscure matter or more of Gor’s tangled mesh. It could represent the burdens each of us carry; the worries that hinder our freedom. Another ink-work speaks of the African predicament. This time the nude man carries a platter heaped with human figures that look just like him. It acts as powerful metaphor for how Africans will carry the pain and problems of their fellow men, who also suffer at the hands of the endemic inequality and the general hardship of their lives.

Untitled, 2014.

Gor’s ink drawings are certainly alluring and seem to speak of the nature of human evolution and our place on this planet. A nude male, natural and vulnerable, looks down at the Earth, heavy with contemplation. Meanwhile the grey matter or his advanced thoughts swirl in a ball far above his head. He seems to be asking a primal question: what is this life is all about? What does it matter to be so civilized, such a deep thinker, so smart, and still exist in a world where discontent is rampant and the sting of life is ceaseless. You can feel the turbulence and turmoil in the mind of Gor’s men.

Untitled, 2014.

Untitled, 2014.

Before he heads to South Africa later this year for school, Gor is in his hometown Kisumu (where he was born in 1983), holding his latest exhibition, which he says is inspired by childhood memories. Perhaps by diving into his early life – his beginnings – he hopes to better understand his vantage point. Although highly unlikely, if we are lucky, we might get a quote or two on what he has discovered about himself. Fortunately for Gor, even though he is quite stubborn and very adept at avoiding interviews, his work in most instances is provocative, tells its own story, and can in fact survive and thrive without his presence.