Hamza Halloubi (Tangier, 1982) in Akinci, Lijnbaansgracht 317, Amsterdam

September 6 till October 10.

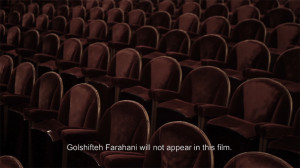

Golshifteh will not appear in this film, 2014 (film).

Passages

Sophie Calle

Hamza Halloubi

Stéphanie Saadé

Imogen Stidworthy

A passage implies transition. It involves a movement, a displacement from one point to another, from one state to another. It also implies time; a present point towards a past event. However, the past is not the point of focus, being incorporated into a movement towards the present and even hinting out to something beyond is.

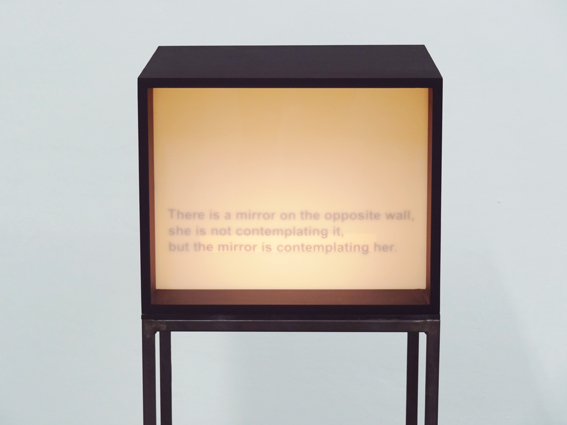

28 seconds, 2012 (video-installation).

28 seconds, 2012 (video-installation).

About Hamza Halloubi:

A CONVERSATION WITH ELODIE EVERS

How did you first got in touch with art and when you decided to become an artist?

I don’t really remember dates. It’s not that important to me to remember when I started drawing or painting. I didn’t decide to become an artist; I make art because I can’t do something else. When I was a student in Tangier, I used to work in a factory during the summer to make some money. We used to work six days a week and ten hours a day, for what amounted to something like fifty cents an hour. I learned, at a very young age, the meaning of a job in a capitalist world. I still remember those nice and generous workers telling me: “Hey Hamza, don’t give up on your studies so that you don’t end up like us.” When I arrived in Brussels to study art, I found out that even with my secondary school diploma in Art, I still wasn’t able to pursue a degree in the visual arts. I passed a number of exams in order to study visual arts. I spent six years in a bourgeois Francophone vocational school in Brussels, not because I was interested in the lessons, but only so as to be able to spend my time reading, to further my autodidactic education, and especially so as not to be obliged to work on a production line. In sum, if I had to give a reason for why I make art, it is because I don’t want to work on a production line.

Letter from Tangier, 2014 (video-installtion).

Letter from Tangier, 2014 (video-installtion).

The preoccupation with issues of home(lessness) and exile is a recurrent motif. Do these subjects stem from your own biography?

I was born and raised in Tangier, Morocco, and I came to Belgium in 2004, when I was 22 years old. I am an exile, an emigrant, but my biography isn’t that interesting for my art. It’s just a starting point. There is sentence in Adorno’s Minima Moralia which says: “The house is past.” My first couple of years in Europe were the experience of the reality of losing home. It is an idea that differentiates modernity. Modernity is an orphaned period in history.

You just referred to Adorno. Literature, and philosophy in particular, seem to have a big influence on your work.

Where do you draw your inspiration from?

Literature interests and inspires me, but the line from it to my work isn’t direct. It’s rare that I read something for a piece. The question of inspiration is a very complex one for me. I recently made a short video entitled 28 Seconds (2012), which shows an African man looking at a photo of a Puerto Rican woman by Diane Arbus. A very simple movement of the camera stages a confrontation of the two gazes. The work shows the influence of everything I’ve read over the years about orientalism, about how the West sees the East. But I was only able to make a work on the question the moment I hit upon the idea for this configuration and camera movement, and that’s more technical than theoretical.

Untitled, 2013.

Untitled, 2013.

Let´s talk about (…) Nature Morte (Still Life, 2013), which is a tribute to the Italian painter Giorgio Morandi. As often in your work, you confront two very different storylines. In this case, images of Morandi’s still lifes contrast with those of the social upheavals of his time. Where did the idea to devote a film to Morandi come from?

What I wanted was to explore the relationship an artist entertains with the social and political events of his era. Over the past few years, with the political situation in the Arab world being what it is, a number of artists there have reacted, swiftly and directly, to the events around them by making very political work. As for me, in this urgent moment, I wanted to make a film about Morandi, to show how the example of an artist who lived through one of the most frightening moments of 20th Century history and was able to continue painting his small still lifes!

I have the sense that you see it as a film about the general question of art’s “usefulness” and timelessness. Where do you see yourself and your own work in relation to Morandi?

I don’t think Morandi wasn’t affected by the events of his time. But his role was to do what he had to do as an artist, and what painting can (still) continue to do, whatever the situation. The question that worries me is: how to produce an artistic work that is artistically convincing, before being politically engaged? Or to paraphrase Walter Benjamin: The political tendency of a work can be politically correct only if is artistically correct. Perhaps what attracts me to Morandi is his distillation of painting to its essence.

Where as you are interested in the distillation of cinema to it´s essence?

Yes. I try to distil cinema to its most basic, elementary means: a cinema that registers and transforms the real.

Modele, 2014 (video-installation).

Modele, 2014 (video-installation).

Do you mean Morandi was political because he stepped back and did what he had to do?

I don’t define Morandi as a political artist! In the film, I try to show images of his still lifes and images of the political events of his time. And then observe what that produces in the audience. For me, the simple fact of continuing to paint rows of boxes and bottles in the middle of the 20th Century is a political position. Mahmoud Darwich called upon Palestinian poets to “clean Palestinian poetry of stones.” He asked them to write about subjects other than politics, otherwise, he said, “Israel will not only occupy our land, but also our poetry.” That runs counter to Adorno’s claim that it is “barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz.” I think the opposite: to write poetry in times of crisis is the strongest, most political act there is. That means that poetry can live, whatever the circumstances!

The films are quite low-tech. The quality of the recorded image doesn’t seem to be your priority. Can you explain your general approach when working on a film? Do you do the camera work and the editing yourself, or do you work with a team?

I don’t film much. Before I pick up the camera, I need to assume a position. It’s only when I have an idea that I start filming. Sometimes I film the same thing several times over many years. But the quality of the recorded image is important to me, though I guess we need to see what we mean by “quality.” I feel very close to filmmakers from the early days of cinema. You can feel how fascinated they were by the simple images of the real they captured. There are also contemporary examples of this, like Warhol and Kiarostami. Who cares whether the image was shot using a sophisticated or an everyday camera?! So: no editing, no team, no sophisticated material – it’s just not professional! It’s not even amateur! Since, nowadays, even amateurs invest a lot on the films they upload on YouTube. They’re an important clientele for the film equipment industry. Warhol says in an interview: “Anybody can make a good movie, but if you consciously try to do a bad movie, that’s like making a good bad movie.”

There is very little editing in your films, which gives them their very own, special atmosphere of quietness and real time.

Many of my films are long takes, with no editing. And even when there is editing, it’s very basic. I’ve tried to distil and distil, until the essential is all that’s left.