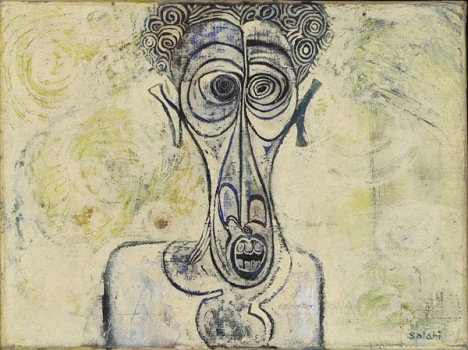

This work of Ibrahim El-Salahi is part of the Tate Modern Collection

Reborn Sounds of Childhood 1, 1961-1965.

About:

Born to an Islamic teacher in Sudan’s second city, Omdurman, his first foray into art was decorating the writing slates at his father’s Qur’anic school. After failing to get the grades to pursue medicine, he began art studies at Khartoum’s Gordon Memorial College (named, ironically, after a British colonial hero killed by the Sudanese), and by the time he won a scholarship to London’s Slade art school in 1954, he was well-versed in figure-drawing, perspective and the western view of art history. Salahi had little concept of himself as an African artist, though. Many African artists and writers of the period – such as the poets Aimé Césaire andLéopold Senghor, founders of the Négritude movement – discovered their identities during studies in the west, faced with hostility and cold weather.

Selfportrait of Suffering, 1961

But he thoroughly enjoyed London. “I found it fascinating. I discovered Cézanne, Giotto and other European artists. There were only a couple of instances of racism. There was one student, a boy from New Zealand, who got very angry when I danced at Slade parties. He had two left feet, and he’d say, ‘You bloody nigger’. But I didn’t pay attention. If you’re not looking for these things, they don’t bother you.”

His moment of self-realisation came when he returned to Sudan in 1957. “I organised an exhibition in Khartoum of still-lifes, portraits and nudes. People came to the opening just for the soft drinks. After that, no one came.” Sudan had never seen a event like it, and it was, he says, “as though it hadn’t happened”. Following a couple more similarly unpopular exhibitions, he was “completely stuck for two years. I kept asking myself why people couldn’t accept and enjoy what I had done.”

Vision of the Tomb, 1965.

He began looking for what was missing – what would allow his paintings to resonate with the people around him. What caught his eye were Islamic calligraphy and decorative patterns. They were everywhere: in houses, offices and shops. “I started to write small Arabic inscriptions in the corners of my paintings, almost like postage stamps,” he recalls, “and people started to come towards me. I spread the words over the canvas, and they came a bit closer. Then I began to break down the letters to find what gave them meaning, and a Pandora’s box opened. Animal forms, human forms and plant forms began to emerge from these once-abstract symbols. That was when I really started working. Images just came, as though I was doing it with a spirit I didn’t know I had.”

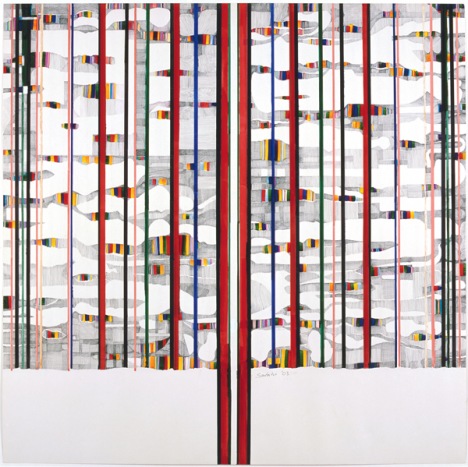

The Tree, 2003.

In 1961, he visited Nigeria, met the writers Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, and became aware of a renaissance under way across the continent, with writers and artists in far-flung areas from all over taking from traditional art to create new forms for a new era: Senegal’s Ecole de Dakar painters, Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko and many others in Nigeria, Mozambique’s Valente Malangatana. It was Africa’s great modernist moment, and Salahi’s work fitted the bill.

“It was exciting, but also frustrating, because there was little response from the rest of the world or even Africa itself. There was a big exhibition at the Camden Arts Centre [in London] in 1969, with artists from all over Africa. But after that, everything went quiet.”

The next big moment, he believes, came 26 years later, at the Africa 95 Festival in London, from which he dates a growing global interest in modern African art. The intervening years weren’t entirely without incident, certainly not for Salahi himself. He participated in the Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar and the Pan-African Festival in Algiers – events that have become legendary milestones in African culture. He undertook residencies in New York and Brasilia, and served as undersecretary for culture in Sudan from 1972 to 1977, under the Nimeiri regime. It was in that time he was imprisoned. “My cousin had been implicated in an attempted coup, but I was never charged with anything,” he says.

His release was as sudden and unexplained as his detention – and he emerged to find his governmental salary had been paid throughout. “I started to feel I was losing touch with reality,” he says. While he wanted to see the downfall of the system that imprisoned him, he accepted an offer in 1977 to leave Sudan and set up a culture ministry in Qatar. For his whole 21 years there, he didn’t tell a soul he was an artist.

They Always Appear, 1966-68.

In 1998, he moved to Oxford with his second wife, Katherine, a British anthropologist. To this day, he will only measure his success in the west by the amount of movement it sparks in Africa. “I’ll give you an example,” he says with a sigh. “In 2011, I went to Algiers for the opening of a new modern art gallery. We waited and waited. Finally we were told the event was cancelled because the culture ministers of the African countries didn’t want to come. This is what we’ve put up with. But we’ve kept on working. And now, at last, it feels like a door is opening.” (From The Guardian, July 2013)