‘Going to the Church’ (1941) is in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington.

Art and Life of William H. Johnson

(text Smithsonian American Art Museum)

American painter William Henry Johnson led an extraordinary, art-filled life. Born into humble circumstances in Florence, South Carolina, Johnson recognized early that his aspirations of becoming an artist were unattainable in the segregated South. In 1918, he migrated to New York City where he was soon admitted to the prestigious art school, the National Academy of Design. There he excelled in painting, studying with noted artist Charles Webster Hawthorne. In spite of his achievements and awards at the academy, both teacher and pupil realized that Johnson would face many obstacles as a black artist in America. In 1926 upon graduation, with private funds raised by Hawthorne, Johnson departed for France for further study.

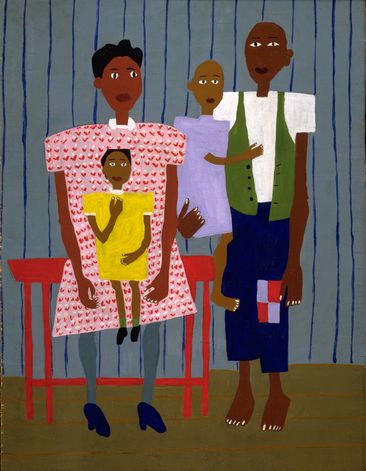

Folk Family, 1944.

Paris in the 1920s was a vibrant place. It was home to expatriate writers and artists such as Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, and Josephine Baker. Johnson quickly fell under its charismatic spell. He settled in the former studio of James McNeill Whistler, located at 86 rue Nôtre-Dame-des-Champs, and soon adopted the multifaceted manner of painting that was then popular in France.

From 1926 until 1929, he lived, worked, and exhibited in Paris and on the French Riviera. From the south of France, in Cagnes-sur-Mer, he wrote to his teacher and mentor Charles Hawthorne, “I have a big space to select from that gives me all the freedom that I need. Here the sun is everything.” He further explained, “I am not afraid to exaggerate a contour, a form, or anything that gives more character and movement to the canvas.” Johnson’s paintings are evidence that this was an inspiring time for him.

Among the many artists Johnson encountered in Cagnes-sur-Mer during 1928 and 1929 were the German expressionist sculptor and printmaker Christoph Voll, his Danish wife, and her unmarried sister, textile artist Holcha Krake. They invited Johnson to join them in their holiday jaunt across Europe. The foursome visited art museums and cultural institutions in France, Germany, Luxembourg, and Belgium.

In 1930, Johnson returned to New York and set up a studio in Harlem. His French-inspired European landscapes and portraits attracted the attention of the New York art world. With his receipt of a Harmon Foundation gold medal, his fame soon spread. News of his award appeared in newspapers in Boston, Nashville, San Diego, Denver, Houston, Kansas City, and even his hometown of Florence. Although he briefly visited his family in South Carolina in 1930, he soon left for Denmark to marry Holcha Krake. From their home in Kerteminde, a small fishing community, the couple exhibited jointly and traveled throughout Scandinavia, Europe, and North Africa. In November 1938, on the eve of World War II, Johnson and his wife sailed for New York.

Street Musicians, 1939-1940.

Street Musicians, 1939-1940.

Johnson joined the WPA Federal Art Project six months later. He was assigned to a teaching post at the Harlem Community Art Center. There he met Gwendolyn Knight, Selma Burke, Norman Lewis, Jacob Lawrence, and other members of the Harlem Artists’ Guild. This was an exciting time for black artists and intellectuals. Perhaps even more than the Harlem Renaissance period of the 1920s, the 1940s was a decade when artists and intellectuals achieved wider recognition and greater profits for their accomplishments, while still maintaining ties to African American social, cultural, and political realities.

Johnson’s search for home and heritage was grounded in his southern roots. Although he had not been home since his visit in 1930, the South was the source of Johnson’s deep-seated memories of endless fields of cotton and tobacco, one-room wooden shacks, rickety wagons pulled by powerful mules and oxen, and stoic, denim-clad black farm workers. In his paintings, Johnson conceptually repositioned the standard folk narratives about rural people and the South along an incredibly modern idiom by using simplified, colorful forms.

Sowing, 1940.

Sowing, 1940.

Johnson’s first major solo exhibition in New York, the first time most of his African American, folk-inspired paintings were shown, opened in May 1941 at the Alma Reed Galleries on Fifty-seventh Street, the heart of the New York art world. The exhibition was reviewed by the two major art journals, Art News and Art Digest, as well as by all the large daily newspapers in New York. It was an auspicious beginning for his second American career.

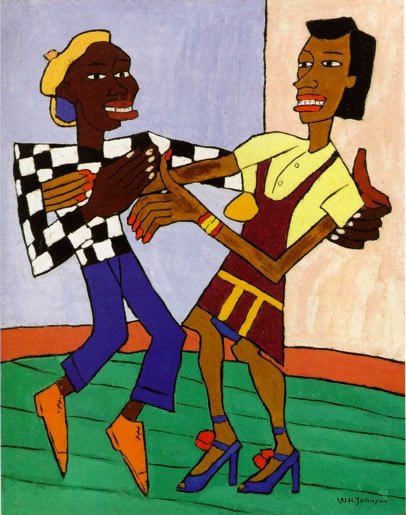

In Harlem, Johnson also scrutinized the assortment of sights, sounds, and people who populated Harlem’s African American community. Mesmerized by the stimulating life around him, he captured the gyrations of the contemporary dance craze, the jitterbug, and documented the hallmarks of urban fashion—broad-shouldered zoot suits, stylishly cocked women’s hats, platform shoes, and vibrantly colored gloves. He also observed the inventive games played by inner-city children. Balancing these light-hearted depictions are darker views of racial violence in this city-within-a-city and families surrounded by poverty.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and America went to war, Johnson produced numerous paintings that explored the contributions of African Americans to the war effort. Johnson’s paintings—images of black soldiers engaged in infantry training, ammunition drills, actual battle, and war-related support services—were not simply visual propaganda. They addressed the heroism and humor, as well as the segregation, of the armed services.

For much of his painting career, Johnson sought to transcend the technical aspects of art in order to capture the soul of his subjects. Summing up his own personal philosophy, Johnson said:

My aim is to express in a natural way what I feel, what is in me, both rhythmically and spiritually, all that which in time has been saved up in my family of primitiveness and tradition, and which is now concentrated in me.

Jitterbugs, 1940-1941.

Jitterbugs, 1940-1941.

Primitivism in this context did not mean a romantic notion about African art or the art of peoples of color. Johnson addressed his own sense of racial and cultural belonging to the “folk,” and how this kinship with people who are bound to nature can result in an art that expresses a traditional, spiritual essence.

After the death of his wife in 1944, Johnson increasingly turned to religious imagery as a means of visualizing his “family of primitiveness and tradition.” This investigation not only provided Johnson with new subject matter, it also allowed him to explore a new design system—one that with its flat applications of paint, simplified renderings of human figures, and colorful rhythms has a direct, impassioned quality.

At this time, Johnson returned to his hometown of Florence, South Carolina, after almost fifteen years. In Florence, he continued to work in a bold and colorful manner, producing a series of portraits of family members and friends. Unfortunately, Johnson’s own world was gradually falling apart. Growing moody and irritable, he was showing signs of mental illness. Back in New York, he began a series of paintings that focused exclusively on historical subjects—famous figures in American history, such as George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, as well as other selected personalities who played important roles in the lives of African Americans. These paintings, which he called his “Fighters for Freedom” series, also included world leaders of the day.

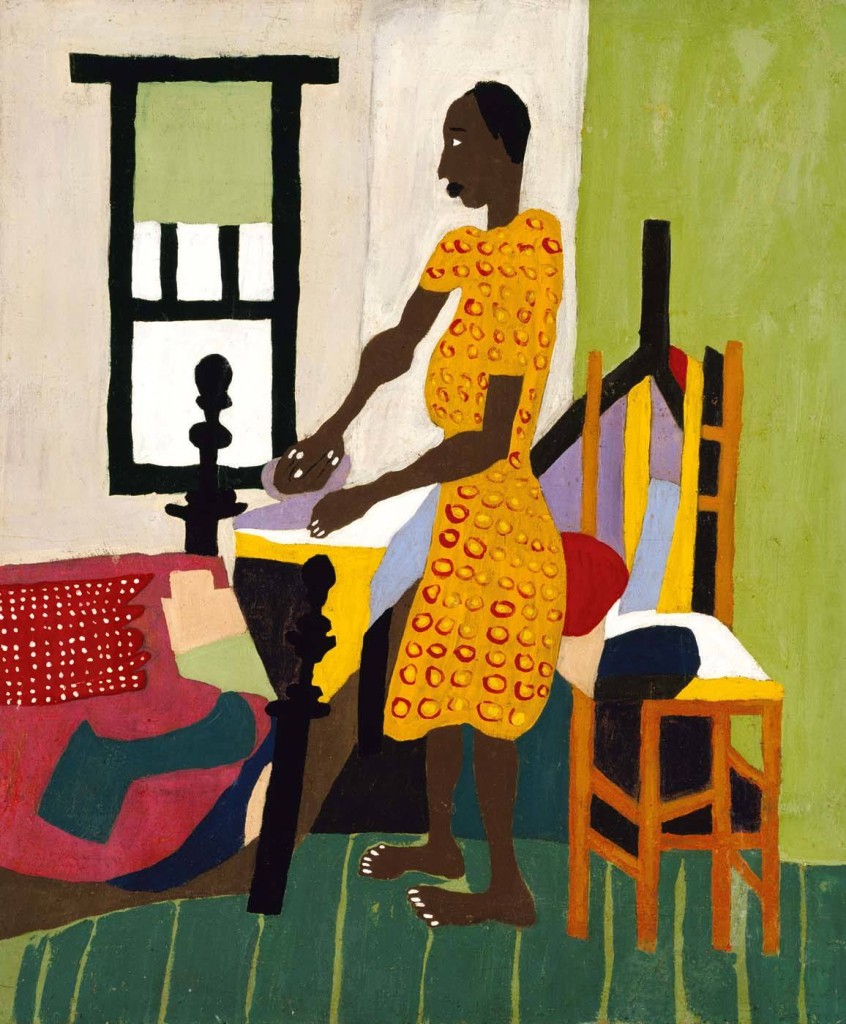

Woman Ironing, 1940.

Woman Ironing, 1940.

In 1946, Johnson returned to Denmark hoping to relive happier times. He was soon, however, diagnosed as suffering from a debilitating mental illness caused by syphilis. Johnson was hospitalized in 1947 in Norway and was later transferred to Long Island’s Central Islip State Hospital, New York State’s largest mental health facility. He spent twenty-three years there, dying in obscurity in 1970. Fortunately, his life’s work—over one thousand paintings, drawings, and prints—miraculously survived those bleak years to bear witness to one of America’s most important, though often neglected, painters.