One of Julien’s aims in his work is to break down the barriers between different art forms like dance, film, poetry and so forth. So far this has been achieved and in doing so, Julien’s viewers are shown how to break down the perceived barriers of sexuality, class, culture and race.

Christabel Johanson on Looking for Langston of Isaac Julien

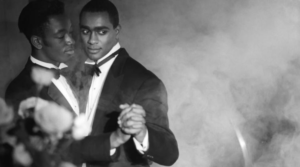

Looking for Langston, 1989, Courtecy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice. Copyright the artist

First published: February 5,2022. Because of the Harlem Renaissance exhibition in The Met in New York, we publish the essay again.

Isaac Julien

“I am interested in poetry”

London-born Isaac Julien is a filmmaker and installation artist. His photography and film work has been celebrated over the years. Looking for Langston garnered Julien a cult following while his 1991 debut feature Young Soul Rebels won the Semaine de la Critique prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

Photos from Looking for Langston have since been lovingly restored; Julien has even exhibited these images across America and Europe including in the Ron Mandos Gallery in Amsterdam.

Isaac Julien, installation view, Looking for Langston – I, Too, Sing America, Galerie Ron Mandos, 2016-2017, © Isaac Julien. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Ron Mandos, Amsterdam, Photo Credit Jack Hems

When previously asked what drew him to art, Julien’s reply of “Punk” may not be a surprise to hear. Much like this subculture the artist himself has pushed the boundaries in his own unique style. After all it was Punk that showed Julien the connection between Art and Politics.

After attending St Martin’s College in London, Julien went on to found the Sankofa Film and Video Collective alongside Martina Attille, Nadine Marsh-Edwards, Robert Crusz and Maureen Blackwood. The Collective was “dedicated to developing an independent black film culture in the areas of production, exhibition and audience”. It introduced audiences to new Film and TV with the aim of diversity particularly from British Black and Asian culture. It was funded by the Greater London Council and Channel 4 which was the new broadcaster of the time. Their productions included several of Julien’s shorts including Who Killed Colin Roach? (1983), Territories (1984) and of course Looking for Langston (1989).

When drawing artistic inspiration Julien has cited an interest in contemporary events, for example Ten Thousand Waves was drawn from the tragic deaths of Chinese cockle pickers in Britain. This may better inform our understanding of Looking for Langston released in the late 1980s amidst the backdrop of the AIDs/HIV epidemic. Although the film harks back 60 years further in time, its parallels to Thatcherite Britain are felt.

Looking for Langston is shot in black and white, mixing real news footage of 1920s Harlem with scripted scenes. The titular name is an homage to Langston Hughes, an American poet whose work was vital during the Harlem Renaissance. The film looks at black gay identity during this period of time through Julien’s lens of non-linear fiction mingled with fact. So it is more of a fantasy imagining of Hughes’ private life during this exciting period of time than a biopic.

“I’m interested in poetry. And in my work it’s very much a sort of poetic quest for a language to express experiences which are part of the everyday experience of people like myself”, remarked Julien in a conversation with the Tate. Indeed the narrative is more like a visual conversation that centres thematically on sexuality, desire, oppression.

The interplay between first-hand footage and staged scenes encourage the viewer to understand a deconstructive language. By playing between fact and fiction we are invited to reclaim a new understanding of contemporary life in Hughes’ time and by extrapolation, the experience of a black (gay) man.

In an interview with the Evening Standard Julien commented that the “innovation in the moving image is taking place in the museums and galleries, not really the cinema. The cinema has a certain classicism if you like: I’m not against it as a form, and I rather like it when artists make films that venture into a more mainstream space, though I’m not sure they can bring all their aesthetics there. I like the idea of transversing different platforms and spaces.” Perhaps this transversing is made explicit within the non-linear narrative of Looking for Langston and certainly the nods to other artistic forms within the film celebrate the innovation found in more traditionally arty spaces.

Hughes’ own sexuality was in question at the time and was never confirmed, although he has been widely presumed gay. Not only was this of note but Hughes was an important contemporary figure being one of the first black men to make a living as a writer. Not only was he a poet but he was also a playwright, novelist and journalist to list his accolades.

Isaac Julien, Pas de Deux No. 2 (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016, Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London. © Isaac Julien.

Whilst Looking for Langston is not a biopic, it does begin with Hughes’ funeral scene in 1967. This scripted scene is an interpretation of that moment. The film peppers real historical footage against Hughes’ poetry and poetry from other writers, juxtaposed alongside images of black men which were principally shot by Robert Mapplethorpe. Mapplethorpe’s usual portfolio included the BDSM and homoerotic subculture of New York’s underground scene. So it is clear that there is an edginess to the film taken from its many sources.

Looking for Langston is told from the perspective of the black gay male vis-à-vis oppression and the social-cultural norms of masculinity in Western society. This is further specified within the African American community. Hughes’ presence in the film is said to be a metaphor for this overall experience and iconic for the time (1989).

Isaac Julien, Stars (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2017, Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

The dreamy sequences of men being sensual with each other are sumptuous and tender, adding both a touch of eroticism and luxury to the narrative. The prohibition era of the period adds a further layer of illicitness, secrecy and mythos that is all too delicious and swoon worthy.

In fact much of the cinematography is closer to photographer than filmmaking (in part thanks to Mapplethorpe’s influence, as well as James Van Der Zee and George Platt Lynes). Julien himself has said “film combines so many of the arts – music, theatre, opera, dance – that they become part of the vocabulary.” This is felt deeply in Looking for Langston’s mise-en-scene, poeticism and artistic fluidity. In fact Julien drew heavily from Van Der Zee’s Harlem Book of the Dead, which focused on Pan-African funerary traditions and their link to African-American culture. This was Van Der Zee’s photobook which has been his most seminal work.

Isaac Julien, After Georges Platt Lynes (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016, Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Looking for Langston was also released at a time when AIDs and the “threat” of being a gay man was heightened. This adds yet another layer to the Van Der Zee allusion; the interconnectedness between life, sex and death has been reverberating throughout time for eons. Here the fear-mongering, social stigma and prejudice faced by the queer community is paralleled between the 1920s and 1980s.

Upon its release in the United States the film unsurprisingly faced censorship. However this was based on copyright issues around Hughes’ poetry. Nevertheless it went on to garner a cult following and won the Best Short Film prize in the 1989 Berlin International Film Festival as well as gaining huge popularity amongst its fan base. Today it is archived in the British Film Institute’s Black Cinema records and is considered a Queer Cinema classic. Julien himself has gone on to gain a CBE for Services to the Arts in 2017.

One of Julien’s aims in his work is to break down the barriers between different art forms like dance, film, poetry and so forth. So far this has been achieved and in doing so, Julien’s viewers are shown how to break down the perceived barriers of sexuality, class, culture and race.