James Barnor’s work is remarkable but not just for the lifespan of years recording culture around the world. In Barnor’s work you can feel the richness of life behind the portraits.

Christabel Johanson on British-Ghanaian photographer James Barnor

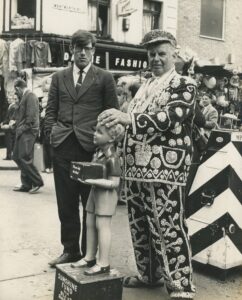

Pearly King Petticoat Lane Market, London 1960s, Courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

First published: October 6, 2021

James Barnor: Accra/London

A Retrospective

The Serpentine presents a major retrospective of British-Ghanaian photographer James Barnor’s work. Barnor’s career spans six decades, two continents and numerous photographic genres through his work with studio portraiture, photojournalism, editorial commissions and wider social commentary.

In Accra/London – A Retrospective Barnor marks the social and political changes of life in London and Accra. Uniquely placed in history Barnor moved between the two cities during the 1950s-80s. The footage his created and archived is where the exhibit draws its first-hand source material.

Born in 1929 in Ghana, James Barnor established the Ever Young studio in Accra in the early 1950s. During this time the city was on the edge of independence and music, conversation and energy buzzed through the nation. In 1959 he arrived in London, furthering his studies and continued working for Drum an influential South African magazine. His assignments captured the zeitgeist of London, especially through the perspective of the African diaspora coming into the city. Barnor returned to Ghana in the early 1970s to establish the country’s first colour processing lab. During this time he continued working as portrait photographer and connecting with the music scene. He later returned to London in 1994.

“I came across a magazine with an inscription that said: ‘A civilisation flourishes when men plant trees under which they themselves will never sit.’ But to me it’s not only plants – putting something in somebody’s life, a young person’s life, is the same as planting a tree that you will not cut and sell during your lifetime. That has helped me a lot in my work. Sometimes the more you give, the more you get.”

Part of the gift of Barnor’s work is derived through the intimate shots he achieves with his subjects. In fact he explicitly sees this as a collaborative process. In his body of work you will find family portraits, commissions, documentary photographs and otherwise. However Barnor’s approach is always collaborative. Before shooting he sits and talks with the subject and together they work together to get the right shot, capture the perfect moment or express the feelings needed.

Barnor’s level of intimacy is a reflection of his passion not just to document but also educate. Recently his 32,000 pictures have been digitised allowing the photographer to easily revisit and review his work, spread the stories and importantly the soul of the photographs to younger generations. This way of reviewing is an important tool in exhuming the lives and faces lost in time and all too often lost in the political and social biases of the world.

For example, life in Accra in the 1950s was buzzing with energy and Barnor remarks on the contrast between the structured studio format and the more candid fieldwork he embarked on. “For me it was like living in two worlds: there was the careful handling of a sitter in my ‘studio’ with a big camera on a heavy tripod, and then running around town chasing news and sports! If I needed a picture, or a new story, I would rush to the Makola market, where people behave most like themselves. I enjoyed this more than studio photography. I would use a small camera. It was good for finding stories.”

Evelyn Abbew, Ever Young Studio, Accra 1954 © James Barnor/Autograph ABP, London

The idea of finding people who would behave more naturally captures the spirit of movements like cinéma vérité; the unveiling of truth hidden between the façade of reality. This spirit lives on in Barnor’s photography. Then in 1957 Ghana gained independence from Britain. Barnor was there to capture the rise of Dr Kwame Nkrumah to Prime Minister and the social revolution about to cascade through the country.

Eventually one of his photos were published in British newspaper The Telegraph. This lead to his work getting much attention from both African and British outlets. He was commissioned by Drum and Black Star Picture Agency to cover Ghana’s transformation and this became Barnor’s break onto the global stage. “I was the first newspaper photographer in Ghana, and I’m proud of that. Newspaper photography changed people’s lives and it changed journalism in Ghana. I was part of this moment.”

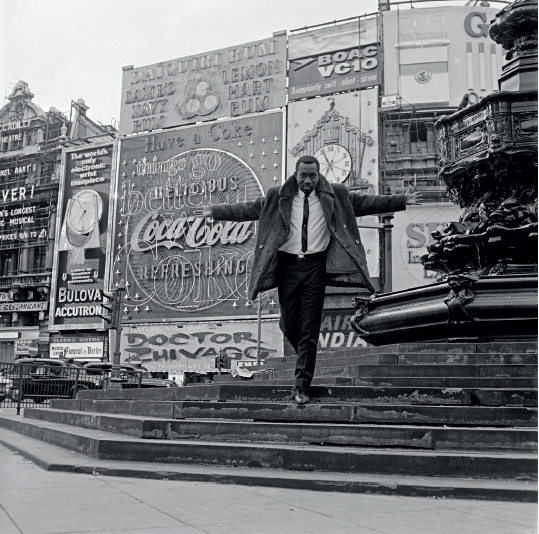

Mike Eghan at Piccadilly Circus, London, 1967 © James Barnor/Autograph ABP, London

Two years later Barnor came to London. There he met lecturer Dennis Kemp and together the duo went around England visiting schools and lecturing using the visual aids they had accrued together. The two men received a grant from the Ghana Cocoa Marketing Board to train and they hosted coffee evenings to discuss photography, African culture and philosophy. Barnor continued working for Drum whilst in the UK and focused on getting models of African descent onto the cover. This is how models Erlin Ibreck or Marie Hallowi got attention and combined with Barnor’s urban backdrops Drum’s covers captured the Swinging Sixties through the eyes of Black diaspora.

Drum cover girl Erlin Ibreck, Kilburn, London 1966 © James Barnor/Autograph ABP, London

During the Sixties Barnor continued honing his craft by learning more about color photography and enrolling at Medway College of Art in Rochester, Kent. Excited to share what he learnt in the UK, he returned to Ghana in 1970 and helped establish the first color-processing lab in the country. Three years later he set up his own studio.

Due to Barnor’s influence in setting up colour labs, the country was empowered to do their own photo processing without outsourcing abroad. People were granted more access to and demanded more color photography. The vibrancy of everyday life in Ghana was able to be captured and nurtured under Barnor’s vision. For instance Kente cloth, a colorful pattern worn in Ghana, was widely worn by people and often their Sunday bests were photographed after attending church. This was the sort of perfect situation to not only promote Ghanaian culture but utilise modern technology in an exciting way.

Salah Day, Kokomlemle, Accra 1973 © James Barnor/Autograph ABP, London

Barnor kept one foot in the music industry and became friends with many musicians whom he photographed on tour. “I was close to the music fraternity too. I knew E.T. Mensah, who played the trumpet and the sax and spearheaded high-life music before all the others. I knew all the musicians. I was taking their pictures.” He was particularly close to a band called Fee Hi and accompanied them to Italy in 1983 as part of an anti-apartheid campaign. Unfortunately though global recession hit and slowed down tours. Barnor returned to the UK and enrolled in a Business Management course. However he retained his passion for music culture and has fond memories of his previous adventures.

James Barnor’s work is remarkable but not just for the lifespan of years recording culture around the world. In Barnor’s work you can feel the richness of life behind the portraits

In October where the world celebrates Black History Month, James Barnor’s archives are a genuine slice of Black history. From grassroots life in Ghana to the burgeoning diaspora scene in London, he provides a candid intimacy of everyday people. Ordinary people during often extraordinary times, without the contrive of a studio or mainstream influence is both a refreshing and educational retrospective.