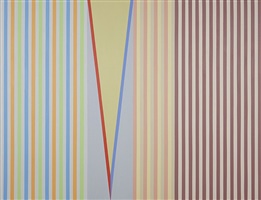

Juju Boogie Woogie, 2013.

I believe that in order for abstract painting to thrive in today’s culture, it has to be re-examined, be repositioned and acknowledged in a new structure that is not predicated on or defined by trends or styles, but rather by a continuum and the inherent human desire for creation and invention, passion and feeling, deconstruction and renewal. It can no longer thrive on theory alone, for even theory risks becoming pedantic over time. Therefore, my aim as a painter is to address those desires and help return abstract painting to its rightful prominence at the forefront of contemporary American art.

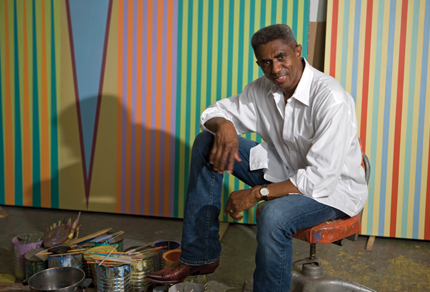

James Little.

Little’s work is equally challenging and satisfying. From his 2003 show at the now defunct L.I.C.K. Gallery in Queens through his more recent exhibitions at G.R. N’Nambi and the Studio Museum in Harlem, Little has been perfecting his variations on a theme, improvising with the diagonal. They cut every which way in his paintings, incising along taped lines with brushwork emphasizing their trajectory. Little works his paint to a satisfyingly gooey consistency, adding wax and paint chips as necessary to more fully body forth color, the true subject of his work. While the architecture of his paintings varies little, the color varies constantly to ever more vibrant effect. Each time you think he can’t make a color hum with greater strength, he does just that, as exemplified by his most recent painting at Sideshow, “Quid-Pro-Quo.” Stunning in its color transitions, Little zips you along from the Naples yellow through cobalt blue and emerald green passages to a rare vertical of cadmium orange that pushes forward so hard that the cadmium red next door recedes.

Little’s work is equally challenging and satisfying. From his 2003 show at the now defunct L.I.C.K. Gallery in Queens through his more recent exhibitions at G.R. N’Nambi and the Studio Museum in Harlem, Little has been perfecting his variations on a theme, improvising with the diagonal. They cut every which way in his paintings, incising along taped lines with brushwork emphasizing their trajectory. Little works his paint to a satisfyingly gooey consistency, adding wax and paint chips as necessary to more fully body forth color, the true subject of his work. While the architecture of his paintings varies little, the color varies constantly to ever more vibrant effect. Each time you think he can’t make a color hum with greater strength, he does just that, as exemplified by his most recent painting at Sideshow, “Quid-Pro-Quo.” Stunning in its color transitions, Little zips you along from the Naples yellow through cobalt blue and emerald green passages to a rare vertical of cadmium orange that pushes forward so hard that the cadmium red next door recedes.

Little’s color revitalizes a vital tradition in painting—that of Barnett Newman, Kenneth Noland, and Ellsworth Kelly. Newman was perhaps the first painter to draw full attention to the properties of isolated color in works such as “Vir Heroicus Sublimis” and “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue I.” At close range, as Newman meant them to be seen, these paintings force one into an optical experience of a singular color that subsumes the field of vision. Little works on a smaller scale, but his paintings are just large enough to encourage this effect. That, coupled with the heavy body of his paint, far more substantial than Newman’s rolled-on surfaces, produces James Little’s unique optics. Little’s painting is celebratory at a time when there’s every reason not to be. In showing Little’s and Willis’s work side by side, gallerist Richard Timperio humbly gives the art world not a sideshow but a main attraction.

Ben La Rocco in The Brooklyn Rail.

Courtesy: June Kelly Gallery New York.