Basquiat was educated by New York which quite literally became his canvas and eventually also his coffin.(….) Basquiat’s life, work and death mirrored New York’s own cycle of growth, destruction and rebirth and is so linked to it that his reputation is almost as notorious as the city itself.

Two quotes from this essay of Christabel Johanson on Jean-Michel Basquiat’s exhibition in The Barbican Centre in London

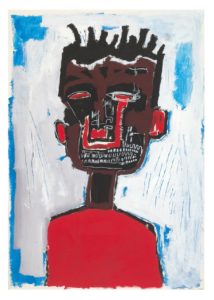

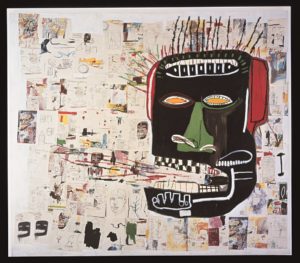

Self Portrait, 1984 (Private collection)

Basquiat Boom for Real

The Barbican Centre in London is currently holding the Basquiat Boom for Real exhibit until 28th January 2018. It presents the main components of his work such as his collaboration with Andy Warhol, the milestone exhibits which featured him and his life in the city. Life in 1980s New York was a different affair to the prolific sprawl of today’s gentrified neighbourhoods. The Manhattan of Basquiat’s heyday was a boiling pot of noise, poverty and creativity and this was the backdrop that not only featured but inspired his art work.

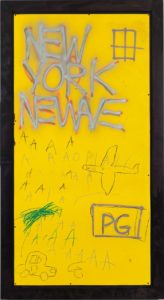

Untitled, 1980 (Whitney Museum of American Art/ARS New York/ADAGP, Paris)

Growing up in the post-Punk scene of lower Manhattan, Basquiat’s first onslaught on the city came when he invented the character of SAMO©. Cooked up for a short story whilst attending the City-As-School academic alternative, SAMO© was a character “shopping for a religion” in a satirical piece for the school’s newspaper. Outside of the school, New York was already brimming with graffiti but when Basquiat spray painted the character’s tag his poetic street art became an instant success. SAMO© (short for Same Old Shit) was born from a time when poverty, crime and unrest was at an all-time high. He and Al Diaz had collaborated together and spray-painted SAMO© phrases all over the city. Then in 1978 The Village Voice magazine identified Basquiat and Diaz, prompting Basquiat to write his final piece SAMO© IS DEAD.

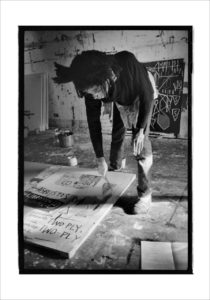

Basquiat painting, 1983 (Photo copyright Roland Hagenberg)

However this was not the last time we would hear or see the character again. In fact in 1979 British artist Stan Peskett invited graffiti artists to feature in his loft Canal Zone loft space. It was here that Basquiat, without Al Diaz, spray-painted a live SAMO© tag. It was during this night that he met Jessica Stein with whom he would later collaborate on with a series of colored Xerox postcards. Once again inspired by his surroundings Basquiat often took motifs such as advertisements, recognisable items (such as the PEZ dispenser logo) and re-worked them by drawing over or rearranging to create an uncanny reinterpretation. These postcards were also away of funding himself as they would be sold outside The Museum of Modern Art before being chased away by the security guards.

King Zulu, 1986 (©The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/Licensed by Artestar New Yok/ Photo Gasull Fotografia)

In 1981 the New York/New Wave exhibit at P.S.1 displayed the counterculture forces around at the time and reflected the energy and often anger of New York’s residents. This was an important milestone for Basquiat’s career as his pieces depicting Manhattan life; the tall skyscrapers, aeroplanes and traffic gained attention from viewers, critics and art dealers. The exhibit launched his career as not only a critically-acclaimed artist but one that synthesised the stimulus of the city to create his own interpretations of the world around him.

*

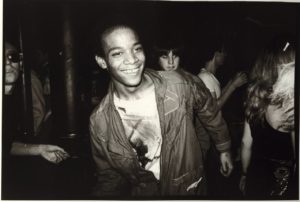

By this time Basquiat had already built a reputation around him as one of the city’s hottest artists. As his reputation grew, so did his fame. At a time when art and other industries rubbed shoulders together The Mudd Club became a beacon of underground notoriety. Film screenings, fashion shows, live music were common place and Basquiat would be found with other notable people such as Madonna, Studio 54 favourite Grace Jones, Sade and Debbie Harry. In a short space of time he had risen astronomically to become the radiant child he was nicknamed.

Dancing at the Mudd Club with painted t-shirt, 1979 (Courtesy Nicholas Taylor)

It was at the Mudd Club that Basquiat met Glenn O’Brien who had written a script for Downtown 81. Basquiat was cast as the lead. The film portrayed the art world of New York in the rough and ready cinema verity style that captured not only the run down city that Basquiat inhabited but the vibrant culture which sprang from it. The film also featured music from the city’s up and coming bands and a cameo from scene-queen Debbie Harry.

Hollywood Africans, 1983 (Whitney Museum of American Art/ARS New York/ADAGP Paris)

However embraced by society as he was, there was still an amount of racism and prejudice that was operating at the time. The 1980s saw the emergence of Hip-Hop as a form of protest and a mouthpiece for black issues and culture, especially from New York. In 1982 Basquiat, artist/musician Rammellzee and graffiti artist Toxic called themselves the Hollywood Africans on a trip to California. Highlighting the importance of representing racial identity the name suggests the stream of African-American actors who starred in films of the 1940s. There was still a huge amount of racial and social angst Basquiat had and these moments show just how much of a political artist he actually was.

*

A year later he and Rammellzee produced Beat Bop. Sounding like a combination of beat box and bebop, two styles that Basquiat was interested in, the track was a construction of typical rap records. It contained common hook and chorus phrases found in many tracks of the time and with the anatomical drawings on the album sleeve, this would suggest an almost conscious forensic deconstruction of the musical form.

Untitled, 1982 (Museum Boijmans-Van Beuningen/Studio Tromp, Rotterdam)

Bebop music and Jazz were two influences that surrounded him always. The artists he admired most, such as Charlie Parker, has all suffered from racial prejudice and of course Jazz itself is an expression of deep emotion. Therefore Basquiat’s artwork was informed in some way with the expression of being a black person. Some pieces conform to this idea in obvious ways such as his Beat Bop track. However Basquiat weaves this through other subtleties. One piece of an American football helmet has afro hair glued to its surface. An icon for many as a quintessential white American sport, the hair engenders the helmet as black. This complements other pieces of work such as his poetry, more specifically one which simply writes FAMOUS NEGRO ATHELETES.

*

This interest in the construction of stereotyping was most apparent in his self-portraits. As a young black artist, he was a figure of intrigue and celebrity and in an interview with Becky Johnston and Tamra Davis, he remarked that often people want to hear more about his life than his artwork. In some of his portraits he is nothing but a black figurehead, silhouetted with just the outline of his hair and eyes made distinctive. By reducing himself to just his color perhaps Basquiat wanted us to explore where the man and the race overlap.

*

What is standout from the exhibit is Basquiat’s love for interlinking source material, academic, cultural, highbrow and lowbrow. As a self-taught artist his source material was vital in fuelling his work. He had an eclectic mix of historic references. He was a huge fan of Leonardo de Vinci as well as African art and philosophy. Therefore perhaps his biggest skill was the synthesis and production of his life’s resources.

Would Basquiat have been the same artist had he not only lived but worked in New York? His pieces are so intrinsically grounded in the city’s character yet bring the world to it. Encompassing different strands of history, culture, symbolism and pop culture, Basquiat’s New York canvas would have been the only backdrop at the time dynamic and frenetic enough to contain and complement his own kinetic style that fused so many strands together.

Glenn, 1984 (Courtesy Private Collection)

For someone as conscious of symbolism as he was of his own selfhood it is easy to see Basquiat fitting into his contemporary settings like a hand into a glove. Andy Warhol and the movement which he catalysed allowed a new form of celebrity; a chance for the weird and wacky counter-culturalists to rise to fame with their own platform and soon to be the status quo. He was the right person at the right time. Nevertheless his legacy lives on with influences on many contemporary artists, especially black artists.

Yet when he was found dead at 27 from a heroin overdose Basquiat became the stereotypical self-destructive artist. However he was far from the arrogant stuck up primadonna you might imagine. From the few formal interviews he conducted, Basquiat appeared to be a gentle, vulnerable figure. New York at the time was bedlam but it was also the breeding ground for revolution. The explosion of art, celebrity and coolness was as dangerous as it was exciting. The dominant culture had no rules, it was hedonistic and the structure which cultivated Basquiat’s work also led to his demise. Being a powerhouse of art, music, poetry, acting whether or not he was considered a Jack-of-all-trades or a Master-of-none is almost secondary to the fascinating backdrop which led to these opportunities.

*

Quoted as saying that he did not attend art school and that life was his art school, Basquiat was educated by New York which quite literally became his canvas and eventually also his coffin. If Basquiat was a master of synthesis then his later erratic drug-fuelled behaviour, mood swings and untimely death was surely also a synthesis of something bigger around him. The city’s boom & bust and its own pulse would have inevitably affected someone so receptive to their surroundings. Therefore one could read a deeper philosophy from the exhibition. Basquiat’s life, work and death mirrored New York’s own cycle of growth, destruction and rebirth and is so linked to it that his reputation is almost as notorious as the city itself.