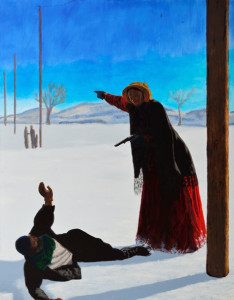

Harriet Tubman en route to Canada, 2012.

KIMATHI DONKOR at JOBURG ART FAIR

Presented by MOMO Gallery Johannesburg in collaboration with Ed Cross Fine Art.

Kimathi Donkor’s dramatic large-scale paintings express pathos, wrath, devotion and irony.

His work is constructed through extensive research both into history and the ideologically loaded genres of Western oil painting. The artist explores portraiture, narrative and art historical themes in his paintings, creating a body of work often conceived in dialogue with other artists from David and Velazquez, to Sargent and Bowling.

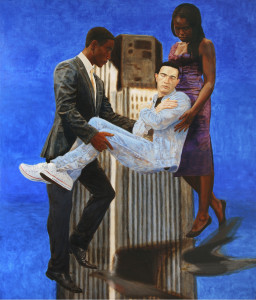

Jonny was born aloft by Joy and Stephen, 2013.

Jonny was born aloft by Joy and Stephen, 2013.

Fragments out of an interview of Yvette Grislé with Donker in October 2013 in FAD.

(Yvette is a freelance writer, also for Africanah.org)

YG: You appear to have a particular interest in colour.

KD: Yes, as a painter that’s your first interest even before drawing, in a sense. With drawing you have line but with paint you have colour. So for many years I’ve been working on ways to integrate really intense and very striking areas of colour. But in a way that presents an abstract element or feel to the work while at the same time conveying a sense of naturalism. I work in a way that is very reminiscent of Renaissance Italian or Dutch painting which works with illusionism, single-point perspective and very well delineated figures. It’s a way of painting that draws you into an illusion. One of the ways I use colour is perhaps as a barrier to that, it stops and reminds you that this is a painting. It’s been constructed and it’s an artificial thing. It’s perhaps a way of allowing a person to appreciate the beauty of the painting.

YG: You also seem to work with symbolism a great deal. The figure of Oshun holds a bell, and the ‘Nanny of the maroon’s’, holds a horn.

KD: Some of the Leaders of Tomorrow have Nigerian heritage. This actually came out on the night of the dinner with Harold Offeh at Tate Modern. We were asked to participate in an improvised calling response, by Offeh, and one of the Nigerian teens used a Yoruba greeting. I thought about Oshun as a figure and the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove in Nigeria where her main shrine is. There is a yearly festival and as part of the ceremonies people ring little brass bells, and click their fingers over their heads to ward off evil spirits and bring good luck. The Orisha religion in Yorubaland is still strong and spread through colonialism and slavery. It’s now present across the Americas (Brazil, Haiti, Cuba) – these regions owe their ideas about spirituality to this Yoruba tradition. This is what I’ve tried to embody here.

Jesus of Lubeck, 2008.

Jesus of Lubeck, 2008.

YG: You’ve paid close attention in these works to the human figure, gestures, facial expressions and so on.

KD: Figurative painters are incredibly sensitive to all the minutiae of the human body – down to the tiniest detail to do with gesture, posture and facial expression. How does the direction of a figure’s gaze draw your eye to a particular section of the composition? All of this is important to the painting’s composition. In this sense, perhaps I am thinking about my own relationship to art and creativity. What are the things that draw my attention, as a figurative painter?

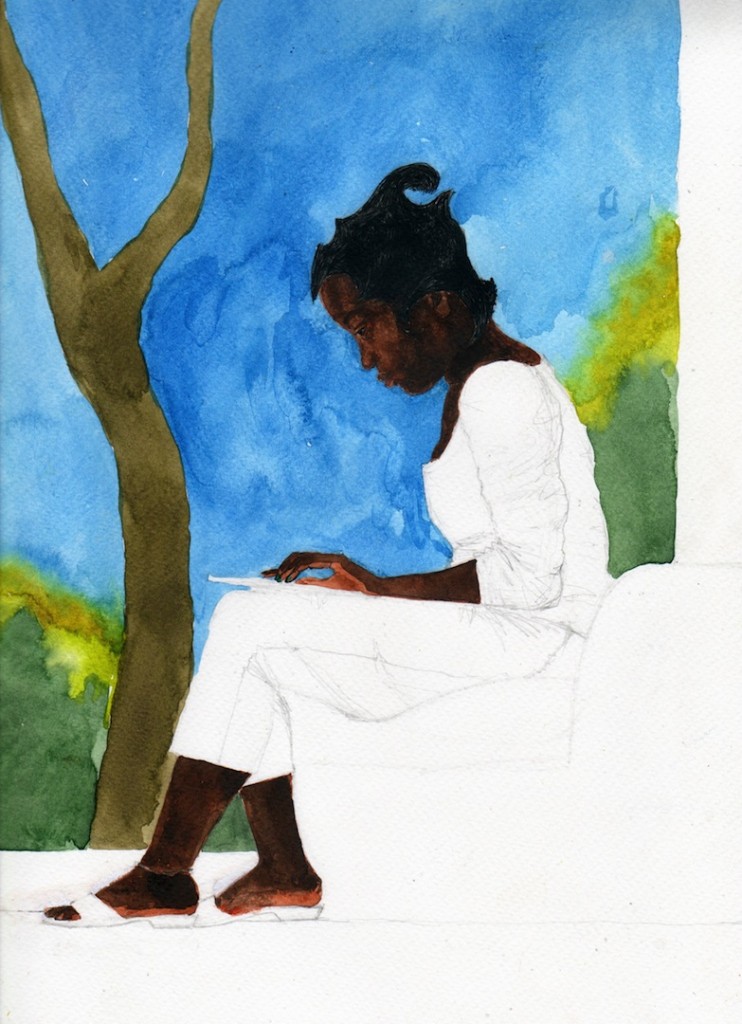

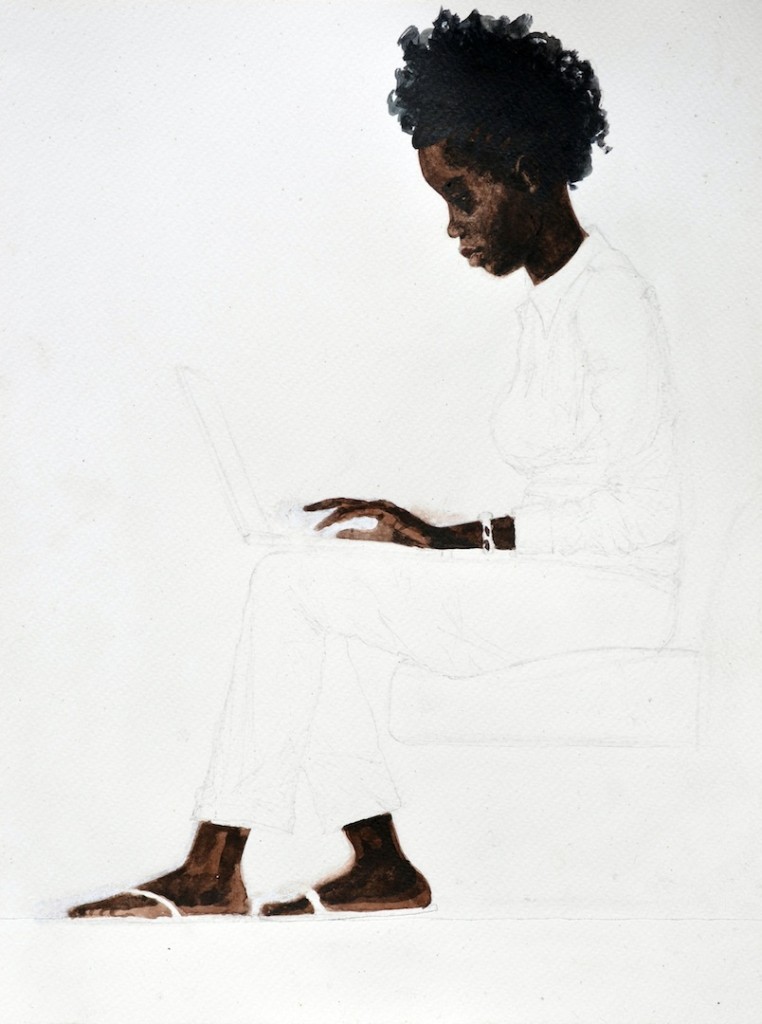

YG: Do you always begin with watercolour and pencil when you’re thinking about new paintings?

KD: I’m interested in how some parts are left empty, while others are coloured in with the watercolour.

I do tend to do quite a lot of drawing. That’s how I begin thinking about my composition. In the first watercolour sketch I coloured in the whole of the surface. I really like a lot of Japanese and Chinese painting. One of the things in Ancient Japanese and Chinese painting is how so much of the composition is left unpainted. The focus is on certain elements and details – quite a contrast to European Renaissance painting, where my main focus has been and where you cover the entire surface and everything is colour.

YG: What interests you so much about the figure of the girl on the laptop, which is repeated in the watercolour sketches, part of the preparatory work for ‘London visitation from Nanny of the Maroons’.

Tablet, 2013.

Tablet, 2013.

KD: From talking to these teens and getting a sense of their interests and their attitude to life I got this very strong sense of studiousness and the desire to succeed. I’ve spent a lot of my life sitting around people who are studious, with their heads in a laptop. This figure could be interpreted in any way because you could be doing anything on a laptop. It is a machine which grabs our attention and we can pour out our interest and creativity in it. The watercolours were part of the process of thinking about iconographic elements, and gradually working them into the composition. I also feel that we are living in an age of increased female empowerment.

YG: Your work as a whole seems to figure many strong female figures.

KD: Absolutely. I’ve been working for many years on a series called ‘Queens of the Undead’, shown at Iniva in 2012. I refer to four ‘Queens of the Undead’: the 17th century Queen Nzinga of Angola; Nanny of the Maroons (born in Ghana she was a Jamaican slave who led a series of rebellions against slavery); Harriet Tubman (born into slavery, in America, she freed herself, and became a leading abolitionist) and Yaa Asantewaa (who led the Ashanti rebellion against British colonialism in Ghana in 1900). What unites these women is their African heritage and their military roles: they all broke the boundaries of female historical characters. They are similar to figures such as Joan of Arc or Boadicea. Many nations have these heroic female figures.

Notebook, 2013.

Notebook, 2013.