John Outterbridge (1933) in:

Nova SouthEastern University Museum of Art

When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South

Till October 12, 2014

When The Stars Begin to Fall, 1974-1976.

About John Outterbridge:

(from Art in America April 2013)

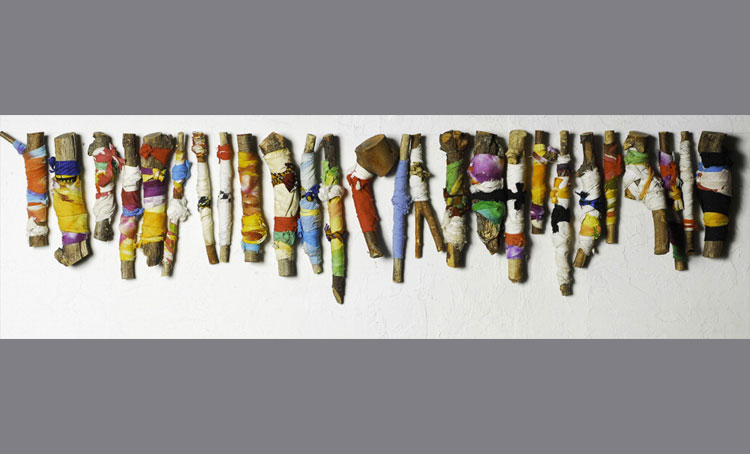

Ragged Bar Code, 2008.

Ragged Bar Code, 2008.

Born in Greenville, N.C., in 1933, Outterbridge moved to Chicago as a young man, where he met his wife and attended the American Academy of Art. In 1963 they moved to L.A., where he largely abandoned his prior pursuits in painting in favor of found-object assemblage. He went on to play a seminal part in the American assemblage movement, particularly as it was adopted among his African-American contemporaries—artists like David Hammons, John Riddle and Noah Purifoy—in the years following the 1965 Watts riots in L.A. Some of his earliest and best known sculptures were cobbled together using detritus from the Watts uprising. From 1975 to 1992, he served as director of the Watts Towers Arts Center in L.A., and has been the subject of group shows and solo exhibitions, notably “The Rag Factory,” at LAXART in 2011-12, his first solo exhibition in Los Angeles since 1996.

Earlier this month, he came by A.i.A.’s offices in New York to talk about, among other things, assemblage as a natural evolution from the folk esthetics he grew up with in the American South.

Let us tie down loose ends, 1968.

Let us tie down loose ends, 1968.

AUSTIN CONSIDINE You were born in the Depression-era, Jim Crow South. Where did you get the kind of exposure to art that inspired you to later make art yourself?

JOHN OUTTERBRIDGE Well, I never called it art until much later in my life. Once a year, there used to be a negro county fair. And this environment was one where everything was visualized. Picket fences were decorated with egg shells and, as a kid, you didn’t know why. It was some kind of ritual. For the culturally rich community that I grew up in, this was like language. There were things like bottle trees all around you because this was the way that people felt and thought about life, and life was predictable and unpredictable at the same time.

What we call folk art was on my street. Buckets were made, pitchers were made, shoes were made. Art and the creative process always belonged to humanity at large. No matter what their complexion, no matter what their posture, people always expressed themselves in some way. That expression, to me, has always been about some form of art. So I grew up not knowing I was doing anything but participating in life. I didn’t see art as a separate thing.

CONSIDINE After finishing art school in Chicago and leaving for Los Angeles, you were mostly a painter. What drew you to sculpture and to assemblage?

OUTTERBRIDGE It was coming to Los Angeles, I think, where I met people like Noah Purifoy and David Mann. I also worked at the Pasadena Art Museum-what you now call the Norton Simon Museum-where I met Robert Rauschenberg and Richard Serra. Mark di Suvero used to leave his tools with me when he was traveling all over the place.

I taught a class for children and adults at the museum, and it had to do with assemblage, painting or anything that the mind could carry. Children came in with those heads wide open. They’d do anything. To me, art has a great deal to do with anything becoming expressive, creative, necessary for human growth and development. And I think art, as we call it, has the audacity to be anything that it chooses to be at a given time. It’s not any one particular thing. It’s many things.

OutCast II, 2009.

OutCast II, 2009.

CONSIDINE And you had that same kind of creative framework already inside of you since childhood, right?

OUTTERBRIDGE My father was a man who found esthetics in his backyard. My mother played piano and clarinet, and read a lot and clipped and saved a lot. I think that was a beginning for assemblage for me, though it was not called assemblage. I think that’s when I started to realize that a torn shade-I could tear that away and that was my canvas. Many of the esthetics existed all around me, done by people who didn’t find it important to put a signature on anything. They just made it. And that’s what I had in my system.

CONSIDINE It sounds a lot like the Watts Towers, where you were director for a time. In their way, having been made by a self-taught artist with found objects, they came to symbolize this nexus of new African-American art at the time, right?

OUTTERBRIDGE Well, it symbolized what was being done in art. You’re looking at assemblage, period. Guys like Rauschenberg, Kienholz and others always respected what Simon Rodia did. Grandma Prisbrey did Bottle Village [in Simi Valley, Calif.] at that time. There were so many folk arrangements all over the world. But we never looked at that beyond thinking that it was vernacular.

The Watts Towers have always been associated with the black community. The community watched the towers grow up. And Rodia was very critical of the times. He felt that ours was a very wasteful society because we throw away so many things. And this is what the towers are made out of-thrown-away crockery and cups and all variety of things that he found that were very attractive.

The Missing Mule, 1993.

The Missing Mule, 1993.

CONSIDINE Still, it sounds like a metaphor about the African-American community at the time-about this notion that out of what the dominant society rejects, one can create something that rises above its surroundings.

OUTTERBRIDGE It related very much to a cast-off, diverse culture. By law it was cast off.

CONSIDINE Is that part of why you think assemblage, in particular, was embraced by this group of black artists?

OUTTERBRIDGE Well, I think that assemblage, like any art form, is that and more. Any art form, to me, has a great deal to do with the fact that anything becomes art that we say is art. You can do anything that you choose to do as an artist.

CONSIDINE What you say makes me think of the New York Timescritic Ken Johnson, who was criticized, among other things, for treating the assemblage-type work of European artists like Picasso and the Dadaists as effectively apolitical while treating the work of you and your cohorts as almost entirely political. It seems to me he was making a mistake in circumscribing them both. Politics was part of your art, but you were also just communicating in a way that felt natural and organic given your experience and upbringing.

OUTTERBRIDGE You’re right. I think also that all things are political. Mr. Johnson made a lot of mistakes when he did not consider as many aspects as possible in making a statement of that sort to such an extensive audience, no matter what its complexion, what its texture.

CONSIDINE No art is either strictly esthetic or strictly political.

OUTTERBRIDGE It’s always going to be both. And no matter what the practice or the people, to me, whether they’re white, whether they dance, whether they’re visual, they will always be looking for a kind of truth. They’ll always be asking, “If this is left, what about right, and all the things that take place between those two extremes?” There’s no difference in the left and the right. But there is quite a difference that is to be discerned and respected in what exists between those two extremes.

Sometimes you ask yourself, “What is art? And what do I care what it is called and what it becomes?” The only thing I know about it is that sometimes it has a tendency to shake me up and to shake what is around me up.

Portrait of Willie.

Portrait of Willie.

About the exhibition:

When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South considers the category of “outsider” art in relation to contemporary art and black life. Situating itself within current art historical and political debates, the exhibition features work by self-taught, spiritually inspired and incarcerated artists, alongside other projects based in performance and social-engagement, as well as painting, drawing, sculpture and assemblage, that make insistent reference to place. With the majority of work created between 1964 and 2014, the exhibition brings together a group of thirty-five intergenerational American artists who share an interest in the American South as a location both real and imagined. Moving between a graphic sensibility, an interest in creation myths and the use of found materials and detritus, the artists reference various classical tropes of blackness as sites of origin—fantastical and performed, important yet perhaps illusory.

Artists in the exhibition include: Benny Andrews, Kevin Beasley, McArthur Binion, Beverly Buchanan, Henry Ray Clark, Courtesy the Artists, Thornton Dial, Minnie Evans, Theaster Gates, Deborah Grant, Trenton Doyle Hancock, Bessie Harvey, David Hammons, Lonnie Holley, Frank Albert Jones, Lauren Kelley, Ralph Lemon, Kerry James Marshall, Rodney McMillian, Joe Minter, J.B. Murray, John Outterbridge, Noah Purifoy, Marie “Big Mama” Roseman, Jacolby Satterwhite, Patricia Satterwhite, Rudy Shepherd, Xaviera Simmons, Georgia Speller, Henry Speller, James “Son” Thomas, Stacy Lynn Waddell, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems and Geo Wyeth.

When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South is organized by The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. The exhibition is curated by Thomas J. Lax.