WhatIfTheWorld Gallery Capetown, SA : Work by Lakin Ogunbanwo, till Nov 15, 2014

About:

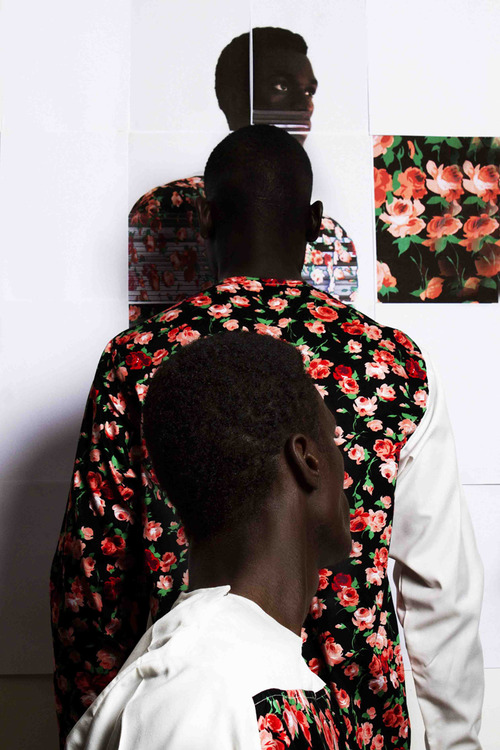

New Nigerian ¬photographer Lakin Ogunbanwo follows in the footsteps of the renowned studio photographers who captured Africa’s popular culture as the winds of independence swept across the ¬continent.

Ogunbanwo’s work comes decades after Malian youth visited Malick Sidibé’s studio, intent on being photographed by the famed portraitist. Likewise, and prior to that, Sidibe’s countryman Seydou Keïta photographed fashionable Malians as they posed before his textured backdrops.

Born in Lagos in 1987, a year after Nigeria was rocked by a military coup, one of many, Ogunbanwo’s love for photography grew as political turmoil engulfed his country. His love was unshakable, he tells me. He practised his art while studying law in Nigeria and the United Kingdom and, when the West African country’s political climate eventually stabilised and Ogunbanwo returned to Lagos, he embraced photography completely.

In his photographs, Ogunbanwo’s subjects seem to haunt the frame. Here are perfect specimens, apparently vacant enough to embody and carry Ogunbanwo’s powerful vision, similar to how expressionless models in the fashion industry are used to carry designs down a runway.

But the people in his photographs are a far cry from those in the works of his predecessors Sidibé, Keïta, Ly and Barnor. Those subjects visited photographic studios to document their existence for their families, for posterity. Their faces, postures, clothing and props expressed vivid emotion as their countries made the transition into independence.

“In my country, the portrait incarnates photographic tradition,” Sidibé told Le Monde’s Michele Guerrin in 2003. “It also documents our history and people through faces, hairstyles, clothes … Clients want their faces and possessions to be seen.”

Besides growing the tradition of African portrait photography, ¬Ogunbanwo says one of the reasons for shooting in the studio is simply the creative control it offers.

“As opposed to photojournalism, documentary or reportage photography, shooting fashion and art in studio means that you – the photographer – are in control of everything in the frame,” he asserts, adding, “I’m a bit of a control freak in that way.”

Ogunbanwo, meanwhile, says that the isolated subjects in his photographs reflect his own personality. He is “a solitary figure, so this work represents who I am. As I tell people: ‘I’m a loner, until I’m not [alone]’.”

The many lonesome figures, presented against bare backgrounds, seem like denizens of a land far away from Lagos, notorious for its overcrowding. Despite being one of Africa’s most fashion-forward cities, it’s hard to avoid reports of state corruption, ethnic tension and unemployment – something not unfamiliar to other African metropolises.

Ogunbanwo reflects on the representation of Africa in the media, and on what is expected from photographers who capture Africans in Africa: poverty, hunger and general disaster.

Copyright: Lakin Ogunbanwo

“As photographers, we all have different stories to tell, and these stories will [be] reflected in the photographs,” says Ogunbanwo, who was recently listed by CNN as one of Africa’s most exciting new photographers.

“Lagos is incredibly busy and always bustling. However, there are parts of the city that are calm and serene,” he says, adding that it is this quietness that influences his work.

(Quotes from article of stefanie jason in Mail & Guardian, November 2013)