Retrospective Lorna Simpson in Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover.

Till January 4.

Easy to remember, 2001 (videowork).

Lorna Simpson’s photography: gold afros, chess players and 50s glamour

(article in The Guardian, March 25, 2014, written by Sean O’Hagen)

When she was 12, Lorna Simpson took part in a dance peformance at the Lincoln Centre in New York, dressed in a gold body suit and matching shoes. It was, she has recalled, “like performing from a black hole – I knew immediately it was not for me.”

What perturbed Simpson as she danced was the feeling that she would much rather be in the audience watching the spectacle. When her parents showed her some indistinct snapshots of her performance, that feeling was only heightened. “I don’t know if that was the moment I felt a need to recapture ‘the moment’,” she later said, linking her disappointment to a “curiousity aboutphotography”. But that was the last time she danced.

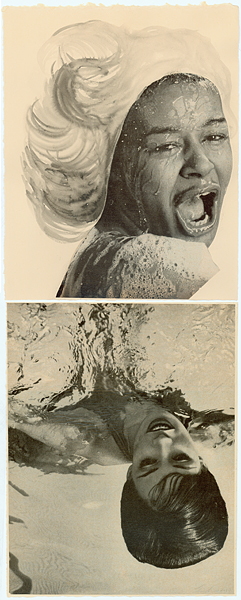

Ebony, 2010.

Ebony, 2010.

The conceptual thrust to Simpson’s photographic art is perhaps best described by the title of her first exhibition in 1985: Gestures/Reenactments. An intriguing new show at the Baltic in Gateshead – Simpson’s first and long overdue European retrospective – shows how the Brooklyn-based artist asks us to doubt and question everything we see.

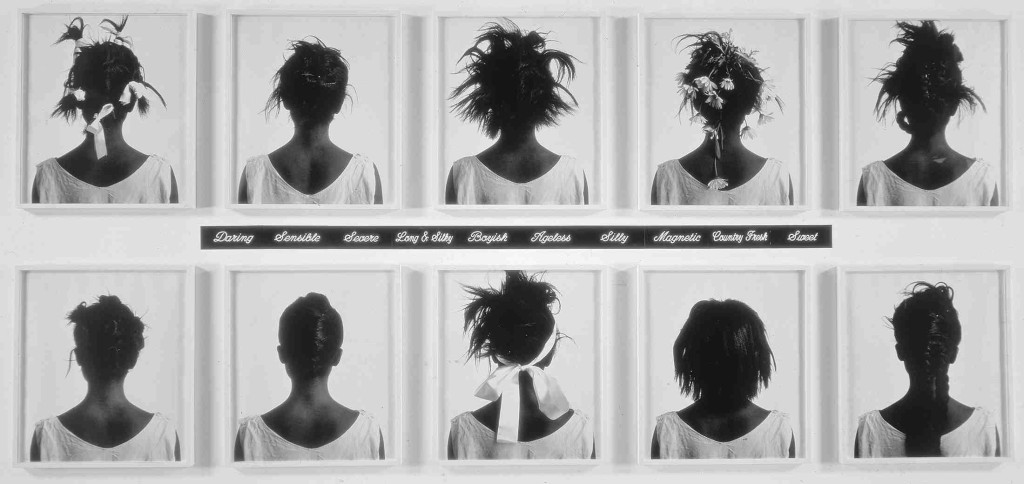

Simpson, who has also been nominated for this year’s Deutsche Börse photography prize, uses still images often accompanied by texts, film and drawing. It’s up to the viewer to make connections in her open-ended narratives. Those connections often have to do with race, identity and memory – but nothing is overloaded. Instead, the works often have a pared-down quality and odd blankness – where a single object, a hairstyle or a wig, can come to represent a whole index of possible meanings or readings.

Stereostyles, 1988.

Stereostyles, 1988.

That blankness is resonant in an early work called Waterbearer, in which a black woman in a white shift dress pours water from two receptacles, one metallic and the other plastic. It echoes a gesture familiar from classical art, except that the woman’s back is turned so we do not see her face. She is, as the critic Hilton Als noted in the Village Voice in 1990, not an icon, but a presence – “the negro presence in the history of art, rarely acknowledged, rarely felt”.

Five Day Forecast, 1991.

Beneath the photograph a text reads: “She saw him disappear by the river. They asked her to tell what happened, only to discount her memory.” These are the words of Phillis Wheatley – a slave who became a poet, and the first black women to publish a book in America – conjuring up a memory of her birthplace in Senegambia. In this context, the words become loaded, suggesting an entire oral history in which memory is all and yet, against the weight of written history, nothing.

The centrepiece of this show, which occupies two floors of the Baltic but only skims the breadth and depth of Simpson’s 30-odd years of work, is a vast two-screen film piece entitled Momentum (2010). Here, the memory of that dance performance from her childhood is transformed into something more playful and questioning. Almost seven minutes long, the performance is mirrored on the screens and begins before the actual dancing, with the dancers standing still. Everyone has gold skin and hair as well as a gold costume, so the film seems both mundane – the dancers wait, pirouette, stand still, look bored – and yet imbued with a Hollywood musical unrealness. Again, there is an odd flatness to proceedings, as if the memory of her initial disappointment is the key emotional determinant here.

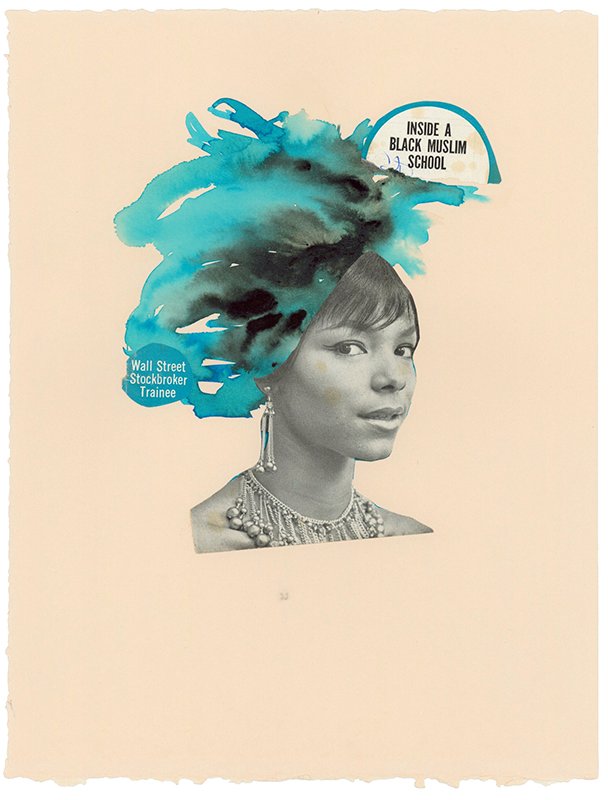

Aspen, 2013.

Aspen, 2013.

I found myself studying faces and gestures – that word again – as I waited for a moment of revelation that never quite materialised. Instead, the dancers twirl and stop, twirl and stop, some more graceful than others, some utterly absorbed, some less so. What you are seeing is the mechanics of performance: the waiting, the doing, the redoing, all made new by an artist’s – rather than an artistic director’s – wilfully undramatic choreography.

Corridor, 2003 (filmstill)

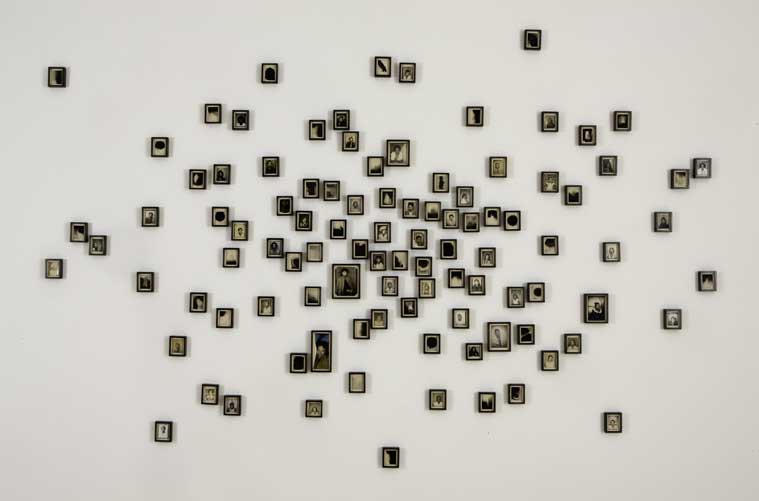

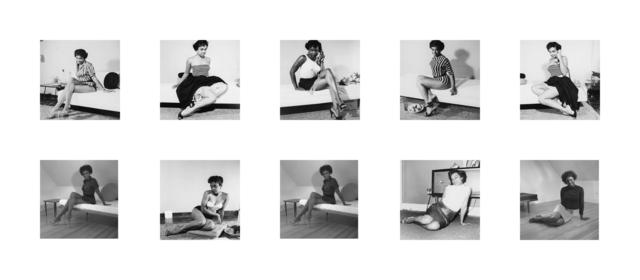

The show’s curator insists this is a retrospective based on “turning points” in Simpson’s oeuvre, so it is interesting to see what she does with found photography, currently one of the key (and near-exhausted) tropes of art photography. In her wall piece, 1957-2009, she uses a cache of black-and-white images acquired on eBay of a young woman – and occasionally a man – posing as if for a 1950s magazine shoot.

Installation view, Brooklyn Museum, 2011.

Installation view, Brooklyn Museum, 2011.

Placing herself in the images, dressed and posing like the woman and sometimes the man, she is again drawing attention to uses of gesture. If the couple are attuned to the gestures required of the glamour magazines of their time, she in turn is attuned to the even more self-concious gestures of conceptual art, which often mimic these original poses. In the process, what once seemed gauche, even innocent, becomes highly stylised and knowing.

Momentum, 2010 (filmstill).

Momentum, 2010 (filmstill).

A more recent video work called Chess (2013), which unfolds in a dark room, leads on directly from 1957-2009. On two adjacent projections, Simpson plays the male and female characters in a game of chess, each character refracted in a five-way mirror. On the opposite screen, the musician Jason Moran plays himself playing the piece he composed for the installation – one screen shows his right hand playing, the other his left.

Installation view, Brooklyn Museum, 2011.

Installation view, Brooklyn Museum, 2011.

The room really does become a hall of mirrors; nothing is what it seems. First up, the male and female characters play not against each other but against themselves. As you watch, they age before your eyes. Here, performance and narrative are fractured and endlessly repeated in a way that is almost overwhelming to the viewer. As with all of her work, you are placed in a position of constantly questioning what you are witnessing, both as a sensory experience and as a piece of art loaded with meanings.

Speaking of her work in 2009, and in particular of Waterbearer, Simpson said: “I didn’t want anyone to have a chance to look at anything in those images except maybe their own convictions.” Her art, then, is a mirror that casts an often oblique reflection and, as such, works much like memory itself.

Courtesy: Salon 94, New York.