M. Tony Peralta: Growing up in a home dominated by Dominican culture, Mr. Peralta began to absorb American art and influences. His obsession with art expanded to include Andy Warhol, Frida Kahlo, Salvador Dalí and hip-hop.

The New York Times on Peralta:

Heritage in All Its Rich Hues

M. Tony Peralta Explores His Dominican Roots

By SANDRA E. GARCIAJAN. 2, 2014

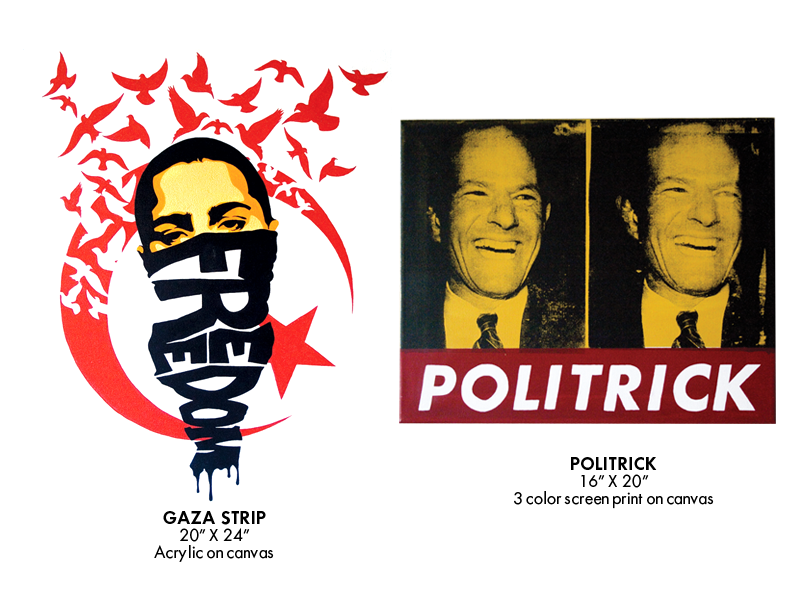

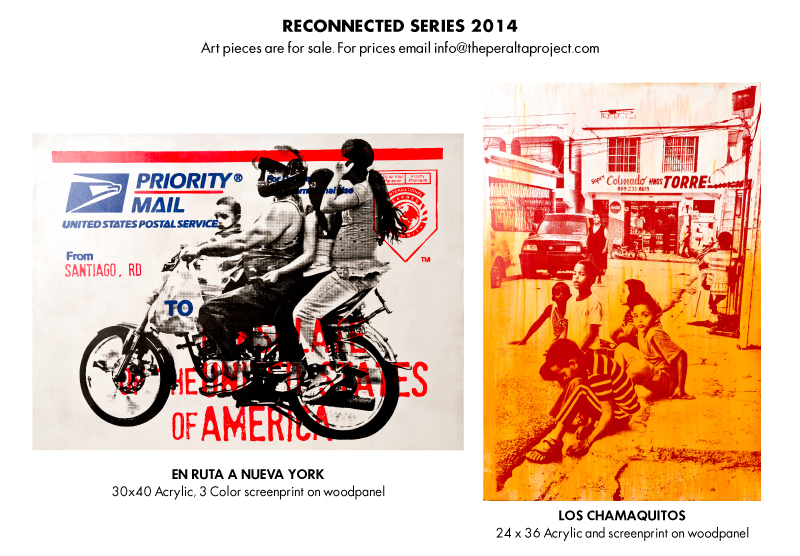

BRIGHT colors pop against the white walls at Renaissance Fine Art, a gallery in Harlem. M. Tony Peralta’s “Reconnected” exhibition is on display, and the Caribbean seems to wash through the space.

The bright hues come from photos screen-printed onto wood panels and canvases. Mr. Peralta took them during a visit to the Dominican Republic in 2011 in an effort to connect to his roots. Until his last trip, Mr. Peralta, 38, who was born in Washington Heights, was better known for art that observed — sometimes caustically — life in New York for a Dominican-American with immigrant parents. This show is about accepting the good and the bad of the Dominican Republic, but still loving it.

In the capital, Santo Domingo, as well as in areas of rural poverty, he captured the image for his work “El Pollero,” which shows a preteenage butcher chopping up chickens while wearing a navy blue cap with a dollar sign on it. Visiting his uncle Marcelo, Mr. Peralta snapped the photos in “Los Chamaquitos,” featuring a band of noisy neighborhood kids, like those in the film “The Goonies,” who hang out on the curb in front of the colmado, a grocery that sells everything from batteries and beers to beans by the peso.

Mr. Peralta, who studied media arts at Long Island University in Brooklyn, described himself as “a graphic designer first.” He recalls that when he was growing up, his half-brother, Robert Ramirez, went to Keith Haring’s Pop Shop in SoHo and bought an inflatable “radiant baby.”

“We used to call it the house baby, because we didn’t know what it was,” Mr. Peralta said in a recent interview.

Growing up in a home dominated by Dominican culture, Mr. Peralta began to absorb American art and influences. His obsession with art expanded to include Andy Warhol, Frida Kahlo, Salvador Dalí and hip-hop. Mr. Peralta says he aspires to be respectful and proud of his culture, as Kahlo’s work is, and as futuristic as Dalí, as commercial as Warhol and as “honest” as the hip-hop trio De La Soul.

At the age of 10, he made his first trip to his parents’ homeland, which was filled with firsts.

“I remember meeting my cousins and realizing they all had my old clothes on,” Mr. Peralta said. “It was the first time I slept in a bed with four other kids. It was the first time that I had to go to the bathroom in an outhouse.”

His visits to the Dominican Republic when he was an adult weren’t as enchanting. During his trip in 2000, he remembers a conversation with a young woman about race.

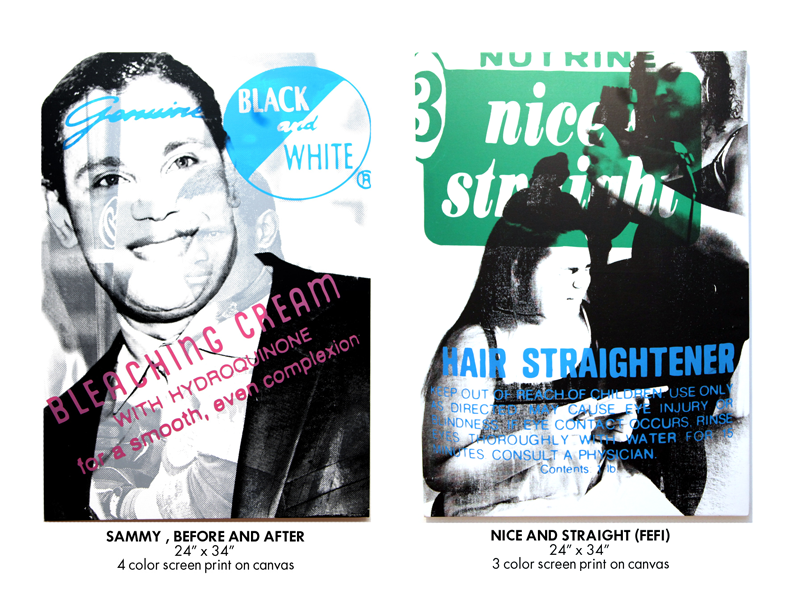

“This girl asked me who do I rather see working as a bank teller, a black Dominican or a white Dominican,” said Mr. Peralta, who is dark-skinned. “ ‘I don’t care, I just want the right amount of money,’ “ he said he told her, but he added that he felt that even the question “represented the backwards mentality in regards to race” in the Dominican Republic. “It was self-hate,” he said, “it was a history of inequality.”

“Even in a country that’s progressed so much, there’s still so much ignorance, and it made me very uncomfortable visiting.”

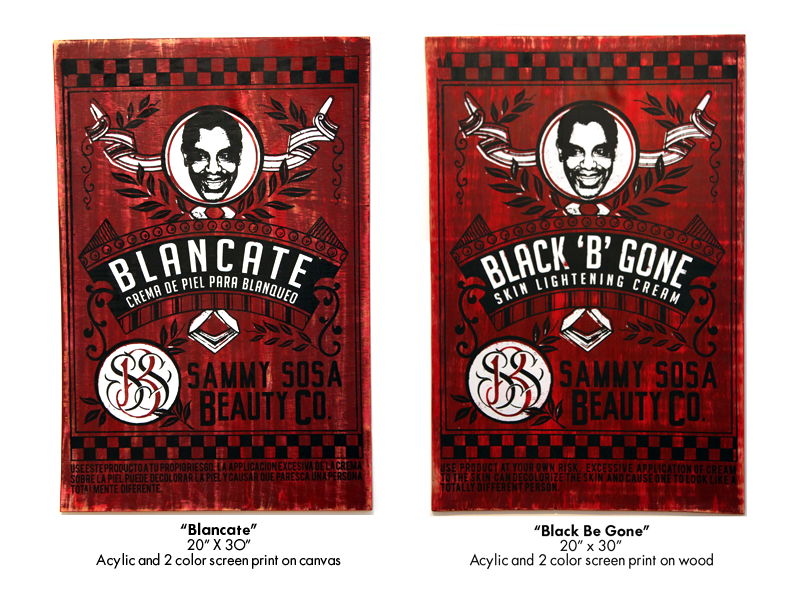

Drawing influences from graffiti and fashion, he satirizes Dominican-American culture in his work. A previous solo exhibition included fictional packaging for skin-lightening cream by the “Sammy Sosa Beauty Company,” and an image of a hair pick with the caption “Bad Hair.”

Drawing influences from graffiti and fashion, he satirizes Dominican-American culture in his work. A previous solo exhibition included fictional packaging for skin-lightening cream by the “Sammy Sosa Beauty Company,” and an image of a hair pick with the caption “Bad Hair.”

Then, in 2011, he went back to the island for the first time in five years. “I had a goal to reconnect with the country,” he said. “I hated going — and I wanted to change that.”

This time, he found something that was “bright and beautiful,” he said. “I wanted my work to give the same warm feeling.”

In “Tia Seferina,” Mr. Peralta’s aunt stares out from the canvas. Her eyes exude affection in a way that seems to say, “I know what you’re up to.”

“She grows her own coffee beans, so when I visit her, I get the freshest cup of coffee,” Mr. Peralta said.

Of his photo of a 90-year-old man, barefoot and riding a donkey in the city of Puerto Plata, he recalled: “He was so happy, and he probably lives the simplest life. Those are the kind of amazing things you see in the Dominican Republic.”

For Audrey Aybar, a Dominican-American administrator at a hair salon chain, the images in “Reconnected” are glimpses of a country she rarely sees. When she visits the Dominican Republic, “I stay in resorts,” said Ms. Aybar, who was born in New York. “When I go back in 2014, I am going to look at the more rural areas and appreciate that.”

She went to see Mr. Peralta’s exhibition on opening night in December. “It brought tears to my eyes, because I feel he’s a voice that speaks to so many of us,” she said.

Abigail Garcia, a Latino studies student at New York University, has never visited the Dominican Republic, her parents’ homeland. “This exhibit is a really great way to keep our generation in touch with our Dominican heritage,” she said, after touring the show.

But Cynthia Cobbs, a communications specialist who visited the gallery and who isn’t Dominican, said that she felt that Mr. Peralta’s message was universal.

“The quest for life is the same, whether it’s the Dominican Republic or uptown or Jamaica,” Ms. Cobbs said. “It’s a reflection of ourselves.”

Copyright: the artist/designer