Africanah.org at 5: We celebrate the 5th anniversary of this magazine with the re-publication of a number of remarkable essays. This one is on Kerry James Marshall. In 2013 he said in an interview with Rob Perrée: “We could not refer to our role in art history, because we did not play a role in that history.” (https://africanah.org/kerry-james-marshall-i-call-attention-absence-black-presence/). Now you can say that Marshall has a place in the Western canon of art. The exhibition ‘Mastry’ made that very clear. Julia Geerlings wrote this article on that show. In December 2016.

MASTRY: KERRY JAMES MARSHALL

It has been one month after Trump won the presidential elections in the United States. I was here in New York City in the middle of the turmoil. Like so many other people I naively thought Trump will never win the election. But we were proven wrong. After Trump’s victory I participated in demonstrations around the Trump Tower and followed the public debates closely. The election of Trump feels like going back to square one after having an African American for president and a woman as a presidential candidate in the US. It’s a nasty feeling I’m still not able to shake off. In this dark month I found solace in a visit to Kerry James Marshall’s massive retrospective at the Met Breuer. The Guardian even spoke of the exhibition as a ‘Godsend’ against the current backdrop of ‘racist demagoguery and national disbelief’.

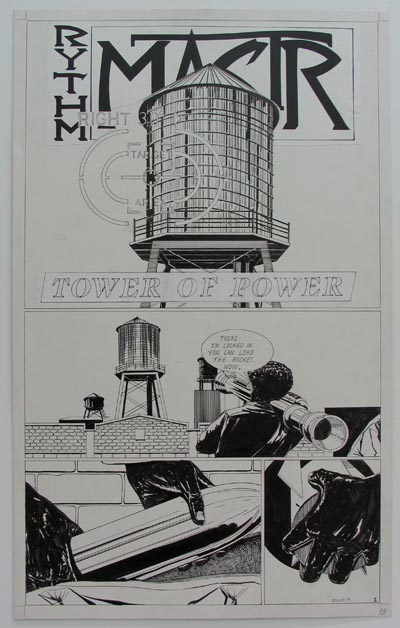

Page Layout for ‘Rythm Mastr’, 1-4, 2004.

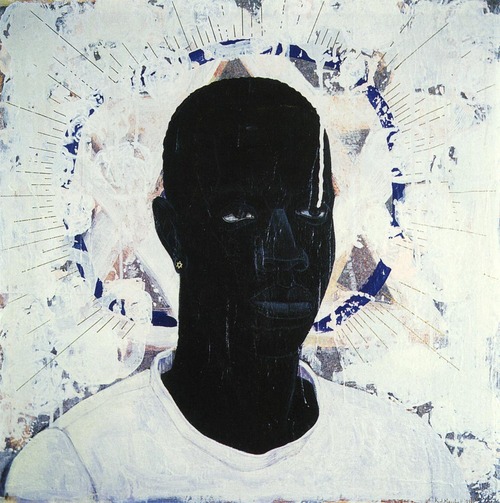

The major monographic exhibition Mastry by Kerry James Marshall (Born 1955 in Birmingham, Alabama) opened in April at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and is currently on view at the Met Breuer (former Whitney museum) in New York City. Marshall is seen as one of the most important artists of the United States and especially in Chicago the city where he lives and works since the eighties. He grew up in Watts, Los Angeles, where the rise of Black Power and Civil Rights movements had a huge impact on his work to come. Marshall is mostly known for his large-scale paintings depicting African-American life and history and using solely extremely dark, black figures to counter stereotypical representations of black people in society and reassert the place of the black figure within the canon of Western painting. The exhibition includes nearly 80 works and spans Marshall’s 35-year career. The misspelling of the exhibition’s title Mastry comes from Marshall’s comic series of a black superhero: ‘Rythm Mastr’. But the title refers also to the American history of slaves and masters as well as the Old Master painters in art history.

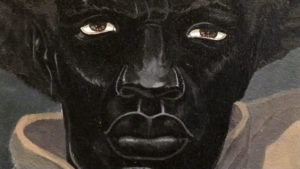

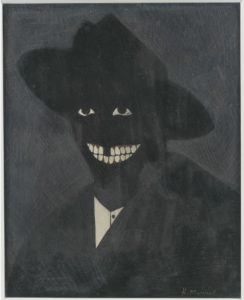

Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, 1980..(coll: Steven and Deborah Lebowitz)

The exhibition starts with Marshall’s earliest works, made right after graduation at Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles in 1978. A quote on the wall reads “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me” from Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man (1952). The novel tells the story of an African American man who recognizes that he is invisible in a racist society. The reading of Ellison’s novel inspired Marshall to produce a series of black-on-black portraits. The most famous is his breakthrough painting ‘A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self’ from 1980. The work is painted with egg tempera (a method of painting used before the invention of oil painting) outlining a man in black wearing a hat that can barely be distinguished from the black background. The exaggerated blackness is in sharp contrast with the whites of the eyes, the white shirt and especially the disturbing cartoonish, toothy grin. The tension is within the ambiguity of on the one hand a racist caricature or blackface and on the other hand a beautifully painted stylized human figure (in the likes of Paul Gauguin and Henri Rousseau). From this moment on Marshall would exclusively paint black people in his work. Not an imitation of African American brown skin tones, but literally ‘black’ paint is used. Different pure black pigments like coal black and mars black are layered on top of each other bringing out blue or golden undertones. No single white pigment is used in the process.

De Style, 1993 (coll: LACMA)

Lost Boys, 1993.

The next room I enter is dominated by two large paintings ‘De Style’ and ‘The Lost Boys’ (both made in 1993). The paintings can be seen as decisive works in Marshall’s oeuvre in terms of achieving the large scale, composition and theme he later would became famous of. In ‘De Style’ Marshall monumentalized the daily life in a barbershop by gracefully portraying five stylish men with lavish hairdos like they were noble men in an old masters painting. The title hints to the name of the barbershop Percy’s House of Style and to the Dutch art movement De Stijl; the use of primary colors can be recognized in the interior of the barbershop. ‘The Lost Boys’ is more outspoken political and an homage to the violent deaths of black children. The two boys are labeled with the dates of their deaths and a tree of life with bullets on the right and a small votive statue at the bottom commemorates these losses. The paintings are both painted in the grand tradition reminiscent of traditional history painting. Marshall stated in the catalogue ‘Artworks you encounter in museums by black people are often modest in scale. They don’t immediately call attention to themselves. I started out using history painting as a model because I wanted to claim the right to operate at that level.’

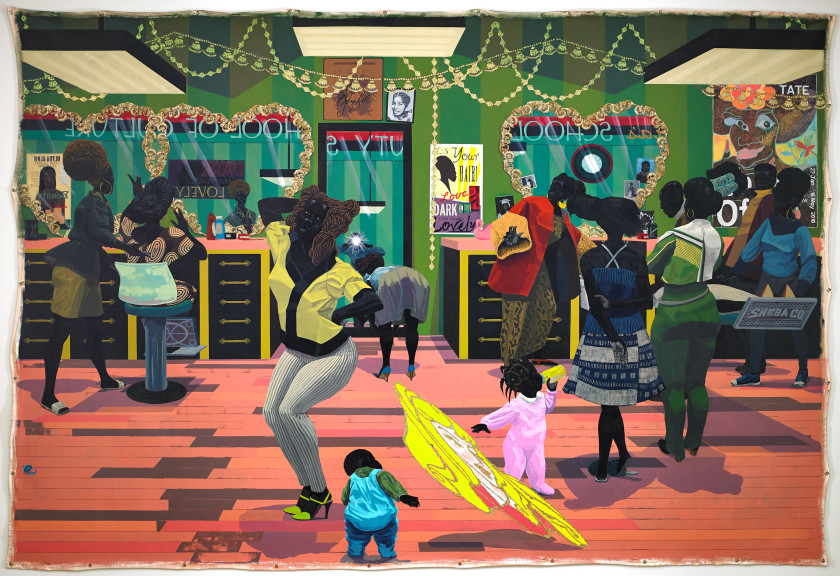

School of Beauty, School of Culture, 2012 (coll: Birmingham Museum of Art)

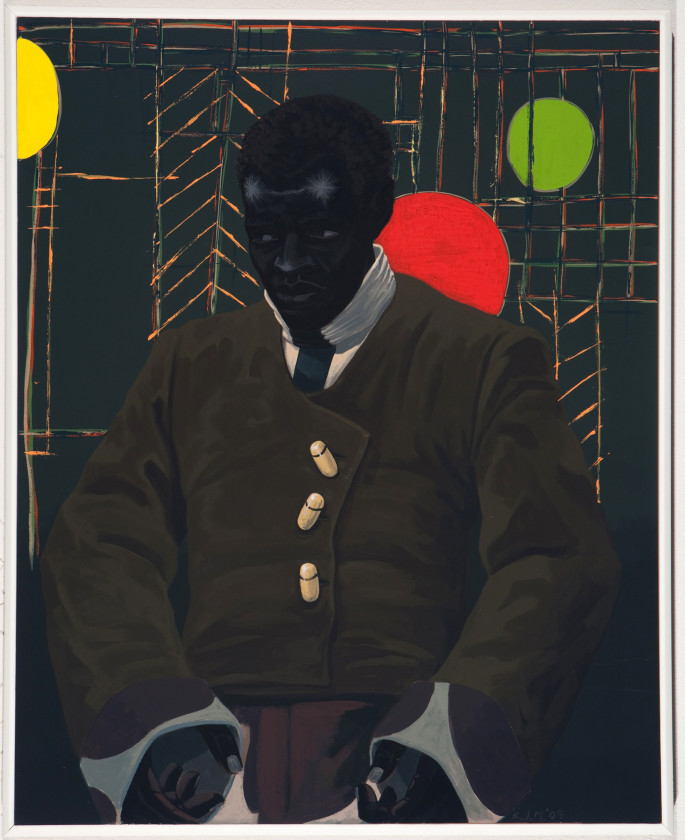

The Actor Hezekiah Washington as Julian Carlton Taliesen Murderer of Frank Lloyd Wright Family,2009. (coll: Hudgins Family)

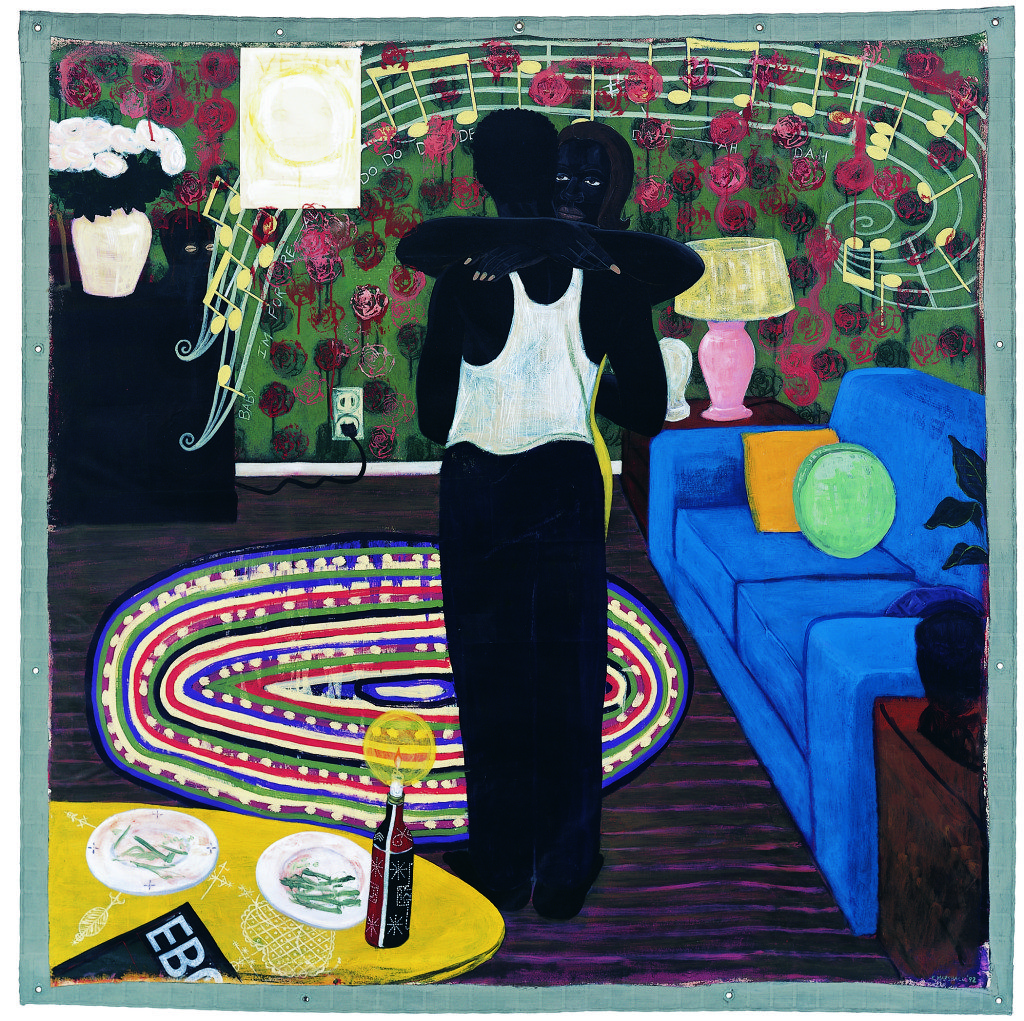

And that he did! I encounter one after the other large heroic painting with monumental black figures involved with everyday African American life; BBQ, boy scouts, living rooms and beauty shops. Some paintings resemble ‘The Lost Boys’, and feel more politically outspoken and others like the beautiful panoramic suburban landscape paintings in the biggest room of the exhibition carry hidden messages. Marshall is correcting the Western canon of art from within and notably by mastering historical exquisite painting techniques sometimes mixed with delightful kitschy glitter and text. In one of the exhibition galleries Marshall curated a group show with works from The Met’s collection; ranging from a painting by Hans Holbein, by Georges Seurat and a sacred object made by the Bamana of West Africa. The extra curated exhibition was not really necessary since it felt like a justification of his work in art history. One other small criticism is the photography installation which is less strong next to the powerful paintings. But overall it’s impressive how he has been able to continue to make mind blowing works for over 35 years without losing much of its impact. Since the two months I’ve been here it’s the best exhibition I’ve seen so far.

Slow Dance, 1992-1993. (coll: David and Alfred Smart Museum ofArt)

The election of Trump is not an isolated event in these times when rightwing movements are gaining ground everywhere. In my own home country The Netherlands the politician Geert Wilders (with equal strange hair) gets more followers for his far right ideas and undiscriminating remarks against minorities. And especially poignant are the violent means of how the Zwarte Piet (Black Pete) discussion is being held and how Dutch celebrities of color are being trolled on social media. Can Marshall’s exhibition after it closes at the Met travel to the Netherlands please?! Perhaps it brings solace there like it brought me here.