Myrlande Constant

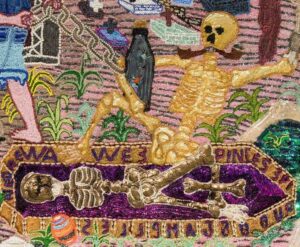

Baron La Kwa

About:

Myrlande constant works in her studio/home, which is located on top of a hill, surrounded by glass-less windows, this is, perhaps, the perfect setting for her flags, which undulate as the wind makes its way into the rooms.

Myrlande constant worked in a wedding dress factory with her mother. After her employers didn’t pay her for her labor, she opposed them and left her job, taking as a severance pay bags with beads and knowledge. She used the sewing and beading skills learned at the factory (the technique used there is called tambour and was developed in france) and started working on her flags. As a result of those situations, in the early 1990’s, myrlande constant became the first woman in haiti to apply the tambour technique in her work, which could be seen as a re-consideration of the making of traditional voudou flags. Moreover, the use of the tambour as a way of building her work, which populated her flags with what at the time were considered as feminine adornments, charged her work with gender.

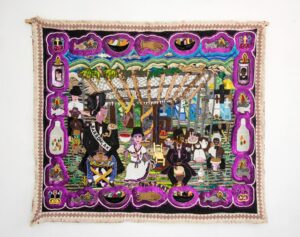

Brigitte and Baron

In her works, constant draws on the back of stretched fabric onto wood while the beading process, what would become the front of the flag, is being formed on the reversed side. Myrlande works through intuition, as she doesn’t see the finished work until the backside has been completed. An artwork that resembles a voudou flag that isn’t seen until it is completed becomes an object worked on from the threshold of the visible. This is a symbol that signifies dualities, syncretism, a belief system, a religion, and a stand-in for those notions, all of which are developed, somehow, almost blindly.

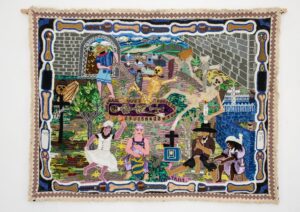

Women, columns, names, and flags

The saying ‘the potomitan[ii] is the woman, the mother, the courage of the family, that, which supports the foundations of her universe” (“le potomitan est la femme, la mère «courage» de famille qui supporte tel un pilier les fondements de son universe” ) correlates women and the omnipresent column standing in a vodou temple, considering them both as centers and connectors. In constant’s work, a type of connector, or, potomitan appears as a unifying element: her last name.

The name constant, which is usually sewn in large and contrasting letters becomes a signifier that runs through various scenes as a constant presence, intervening the narratives of the lwas[iii]. Constant includes herself in her scenes, beading a self-portrait of sorts, surrounded by her reality. This act of naming and charging her works with her last name brings into focus her viewpoint into the voudou ceremonies, offerings, narratives, and the lwas’ roles as projections that live within our realm.

Exorcism

In a work, she presents naked women on top of horses -these are the deities, riding,

mounting people- or figures wearing sun glasses drinking from bottles, next to skulls and penises, where the ceremonial overlaps with the quotidian, and time is addressed as a sum of temporalities while representations interact with each other, developing narratives where sexuality, politics and religion enter the space of naming and law.

This is a law that is crossed by the subjective and is always defying temporal vectors, as it happens in magic. Furthermore, in what we call magic –this also can be applied to the term tradition- what remains as unrealized, or unfulfilled, opens paths where one’s (constant) naming can actualize historical and personal truths, as well as non-academic but highly categorized types of knowledge, as it is the case in constant’s work.

Myrlande constant’s praxis, then, presents knowledge and representations that address the space of the invisible, expanding the repertoire of faces given to the lwas in voudou. Hector hyppolite was the first artist to give faces to the lwas, andre pierre followed up on the task, and now constant is shaping and presenting their faces and actions, from a woman’s perspective, working in port-au-prince, sewing blindly, from the reverse side of planes, extrapolating techniques to re-address institutionalized ways of approaching highly codified objects and signs.

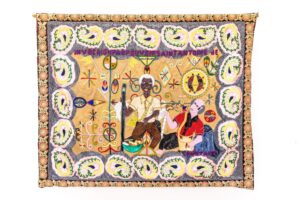

Invocation for Saint Anthony.

Color, anger, prohibition

In voudou, the rada lwas originated in africa and are considered, generally, as benevolent and associated with the color white. The petro lwa appeared in haiti, and in contrast, are aggressive and associated with the color red. The ghede lwa address death and carnality, perform dances, mimic sexual intercourse, and behave irreverently. Their color is black. The rada lwas then, associated with the white color, traditionally point towards pre-slavery before the occupation of the symbolic by imperialistic domination. After the haitian revolution those deities developed a dark side, signaling anger and oppression, or what appears as another side to their roles. Those roles break through from the religious space into the real as unified totalities. This unification also signals syncretism’s embracing of catholic saints, and the merging with their african counterparts, as well as the political dynamics present in haiti’s history. (of note, as mentioned earlier, in the work of myrlande constant, this merging, is also evident in the technical aspect of beading the french technique called tambourine, used for another type of ceremonial garment, the wedding dress, which in turn, re-defines ceremonial voudou flags.)

Color in vodou is codified and the relationships established are clear: the dark side of erzulie freda is erzulie dantor, and cannot -or should not- share the same space with the white side of that lwa. Their coexistence, although both form the same entity, could generate a type of friction in the realm of the symbolic, unleashing a clash, with repercussions, via the magical, into reality.

In voudou, chromatic relationships carry within them functions and tasks. Each lwa is invoked by a certain veve[iv], they are served certain offerings, shown specific colors, objects, food, chants and drumbeats. The veve, (a sign) used in a ceremony is dependent upon the lwa whose presence is invoked. If an artwork has a veve in it, it could posses its owner, and if certain deities interact in an artwork, their colors should be considered thoroughly by the artist. Therefore a dual training is required when addressing voudou in art: not only a formal training is needed, but also an initiation into the religion and its rules, which must be observed as they could impact reality directly, immediately.

Gede

In constant’s work, and moving beyond the traditional appearance of beaded flags and their roles, an approximation, questioning and an unleashing of traditional formats takes place. These operations make evident that a distancing from the didactic and the illustrative is emphasized, as her flags present encounters between the mythical and contemporary issues such as earthquakes, women’s role, social upheaval, sexuality, etc.- we should also note that materially, due to the tambour technique, constant’s work is too stiff to be consider a flag, further separating them from traditional ceremonial flags.

If we consider self-portraiture, blindness, flags, syncretism, sex, religion, names, etc.- we see them all, captured in myrlande constant flags, shining and moving in her studio. Hers is a praxis open to the outside, released through the feminine gaze from the male-dominated institutions that have instrumentalized naming, religion, art, labor, traditions and roles, constantly, until now.

Diego Singh, haiti, 2015—miami, 2018

Copyright Myrlande Constant 2019