Her endeavor at writing with light or rather writing herself into being, being black, blacks out in the face of her existential predicament. Instead of offering a critical reflection on negrophobia, Muholi’s game of parody gets entangled in negrophilia. This isn’t to disavow the potentiality of subversion, but to note the risky slippage of it subsidizing the already existing white jouissance. From this point of view, activism meets stasis.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja on the new photoworks of Zanele Muholi.

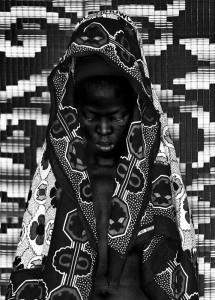

Somnyama Ngonyama 2, Oslo, 2015

Zanele Muholi

Somnyama Ngonyama.

Zanele Muholi’s show Somnyama Ngonyama (hail, the dark lioness) at Stevenson Gallery, Johannesburg invites an interesting debate on race politics. Along the show, Muholi also offers a series of images titled Brave Beauties. Mostly known for her ‘visual activism’ centered around lives of the lgbti black community in South Africa, Muhuli’s work is geared towards an ‘interaction of pixels and actions to make change’ as recently noted by Nicholas Mirzoeff. But if there is something new in this show it is definitely not her activism which I suspect we have become rather too familiar with, but that she has turned the camera more to herself this time.

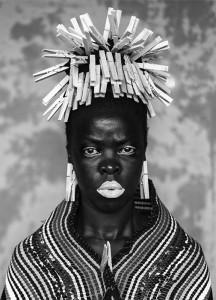

Bester 4, Mayotte, 2015

Muholi turns the camera back to herself, at a very crucial moment, both locally and globally, in which the visual space is fixated with a circulation of crude images of black people. I mean the entire edifice of representational displays, whose appetite for shock and shame has become not just spectacle but also pastime. Thus the appearance of the black in public as an oddity and subsequently, the paradoxical quasi-sympathetic criticism towards that view, has also evolved into a self-pleasuring industry of its own. That is rituals of mindless frays and banter between racists and so-called anti-racists!

The recent controversial utterance by a South Africa white woman, Penny Sparrow calling black people monkeys speaks to the show’s provocations on the race question. We can assume, by turning the camera to herself, Muholi personalizes the discourse and situates her own body in its violence. Here the issue no longer becomes an abstraction felt at a safe distance of the onlooker through the lens; now it directly implicates her, at a corporeal and experiential level. The artists who spends time looking and shooting others with her camera, now indexes her own availability to the violence of the gaze. However at the vanishing end of that gaze, her body, like all black bodies, dissolves into a nocturnal creature of deserved degradation and terror.

MaiD, Brooklyn, 2015.

This new body of work of black and white self-portraits, taken while traveling between Europe, the U.S. and South Africa, is said to be spoofing historical and ongoing rituals of racist caricaturing in the form of blackface. This habitual form of white amusement, is the predecessor of lynching in the U.S., and it has withstood the test of time. While its contemporary outbursts have been linked to right wing outrage, much of it is resonant with the aesthetic accompaniments of much of the well-sequestered racism of white liberal bourgeois circles. If lynching was the inviolable ritual that stabilized rich and poor white communities into solidarity underneath the castrated and smoking carcass of a captured nigger body, blackface wasn’t anything less unifying. In fact, it makes sense that lynching has been pressured out of public life, and blackface has endured and adapted into the common iconography and iconophilia. Trimmed off its familiar and ragged tropes, it has been integrated into the lexicon of contemporary space, and is pervasively enjoyed in our visual culture. This peculiar fondness for blacks, the eccentricity of its ancient violence, has come to subtend much of contemporary visual culture.

Somnyama Ngonyama shows the artists in various poses and acts, innuendos on the globalized terror against the black body. Speaking to a crowd of elated journalists and arts writers at her walkabout, Muholi takes us through the journey of making the work. At the entrance of her gallery, a larger than life size portrait titled Somnyama Ngonyama, consumes almost half the wall. We are all gathered around the photographer, attentively listening. She introduces her collective, Inkanyiso and begins:

‘My name is Zanele Muholi and I take photographs for a living. I take photographs to heal. And I treat photographs as my therapy.’ The word “treat” bears an interesting paradox here. Muholi continues: ‘So Somnyama Ngonyama…it’s a way I responded to a number of …on going racism that our people have faced. And I am using art to articulate that…I wanted to use my body in a nice subtle way. And use the material, you know… I use like simple – I don’t want to say props because I am not performing. Also I don’t want to say performance coz when you try to dissect gender politics, there is that whole thing of gender performativity…I work.’

In these simple but serious words, the artist escorts us into the construction of Somnyama Ngonyama. ‘So this is me! I shoot me!’ She lets us in eloquently, moving from preparation to execution. The big photograph, like the rest of the pictures in Somnyama Ngonyama, have an exaggerated dark complexion, almost reminiscent of the exceptional blackness of the figures in works of Kerry James Marshall. In the description of the work, we find out that Muholi actually uses props despite her earlier abjuration. In the picture, woolen like tresses curls around her face as if she were maned lioness. The work supposedly comments on history and politics of black hair. However what is interesting, she says, commenting on the exceptional darkness of her figures is that: ‘there are no preservatives. I don’t paint my face black because I am black anyway. The least I could do is…put zumbuck.’

Bester 1, Mayotte, 2015.

MaiD 1, Syracuse, 2015

By ‘preservatives’ she’s referring to props like black paint used in the blackface caricatures. Muholi achieves her exaggerated complexion by digitally heightening the contrast of her images. This is how she claims she differs from standard blackface representations. But she might have as well used the ‘preservatives’ because the effect is precisely the same. It is this effect, more so in images like Bester 1, Mayotte and diptych Maid 1, Syracuse, were obvious blackface aesthetic is more congealed. How does this become a way of speaking back? The idea of rummaging the racist archives and its signifiers as a means of “reclaiming my blackness” is an erroneous exercise, especially in this case. It misses the point that on the one side, in an anti-black world, as one Lewis Gordon would have it, ‘there is something wrong with being black beyond the willingness to ‘be’ black.’ It blunders in its assumption that reproducing the stereotype, somewhat diminishes its proclivity to degradation. Thus it’s curious why Muholi masochistically avails her black body in this unreflective way by pandering to the sensibility of the insatiable white gaze. And it isn’t farfetched to assume that Muholi knows too well that a stylised duplication of such tropes goes a long way in the global art market, already predisposed to a violent relation to black bodies. It doesn’t subvert but submit.

Somnyama 1, Paris, 2014.

So out of a desire to speak back to this casually circulated and enjoyed panoply of images, Muholi’s imaginary riposte stumbles into coercion. Her attempt at appropriating power dries up. Power re-appropriates her instead. Her endeavor at writing with light or rather writing herself into being, being black, blacks out in the face of her existential predicament. Instead of offering a critical reflection on negrophobia, Muholi’s game of parody gets entangled in negrophilia. This isn’t to disavow the potentiality of subversion, but to note the risky slippage of it subsidizing the already existing white jouissance. From this point of view, activism meets stasis. Like a minstrel character on a stage whose articulation is scripted and coerced, Muholi’s performs a non-performative resistance. Somnyama Ngonyama might be a series of beautifully taken images, but it is far from reclaiming blackness.