Njideka Akunyili (1983, Nigeria) is one of the artists in the group show ‘Kings County’ , Stevenson Gallery Cape Town. October 9 till November 22, 2014

“The work deals with various themes but the overarching thread is that I’m availing myself of Western painting to seek out a new visual language. In my work disparate elements clash together to give rise to a distinctive yet cohesive whole. The sentence you mentioned refers to an interstitial space of negotiation that I work towards. This in-between/liminal space is referenced a lot in post-colonial discourse – Mary Louise Pratt calls it the ‘contact zone’ and Homi Bhabha calls it the ‘third space’. This transcultural space of constant engagement and appropriation is what I was talking about.”

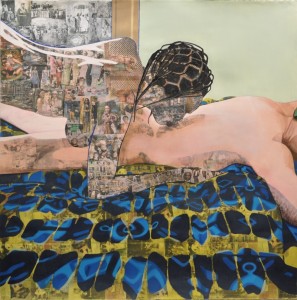

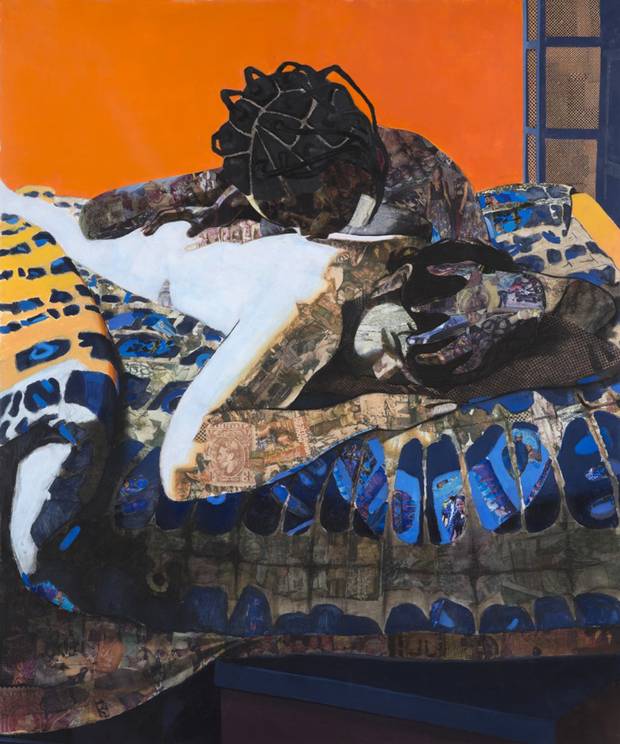

I always face you, 2014.

I always face you, 2014.

“I look at a lot of painters’ painters like Piero, Titian, Velasquez, Manet, Degas and Balthus, also obscure artists like Hammershøi. For drawing inspiration I admire Holbein and more recently the Italian painter Bronzino because I like the sensuality he achieves with his surface using layers of glaze. I also love Kerry James Marshall, Wangechi Mutu, Malick Sidibé, Nontsikelelo Veleko and Yinka Shonibare. I feel a slight content overlap with the last four artists. Literature coming out of Nigeria and the African diaspora also played a part in the development of my work.”

(Quotes from interview in Arise Magazine)

About:

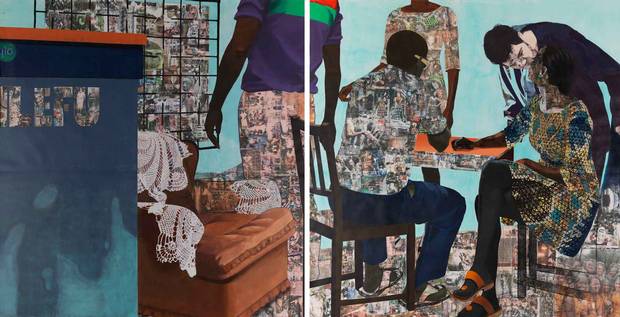

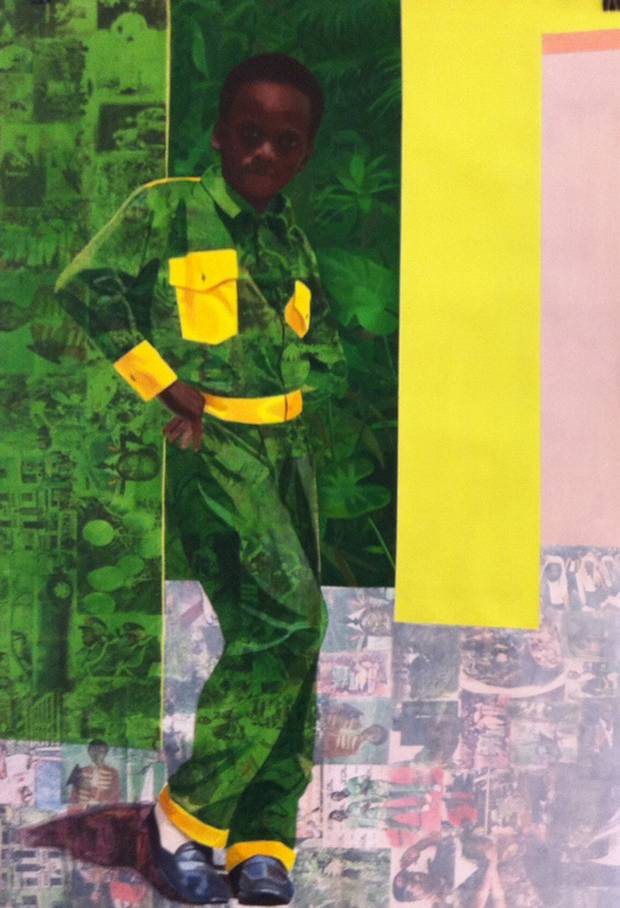

Her paintings, up to 10 feet tall and more than 7 feet wide, are visually engrossing scenes that often include the artist’s family or friends — dancing in a club, talking or embracing on a bed, hanging out with the kids. Ornamental grilles screen some of the figures, preserving privacy and a sense of mystery. The grilles and other visual devices — crisp edges, blocks and wedges of color, shadowed faces — introduce graphic punch and an appealing, posterish verve that is eloquently indebted to the work of the great African-American painter Romare Bearden.

The beautiful ones 2, 2013.

The beautiful ones 2, 2013.

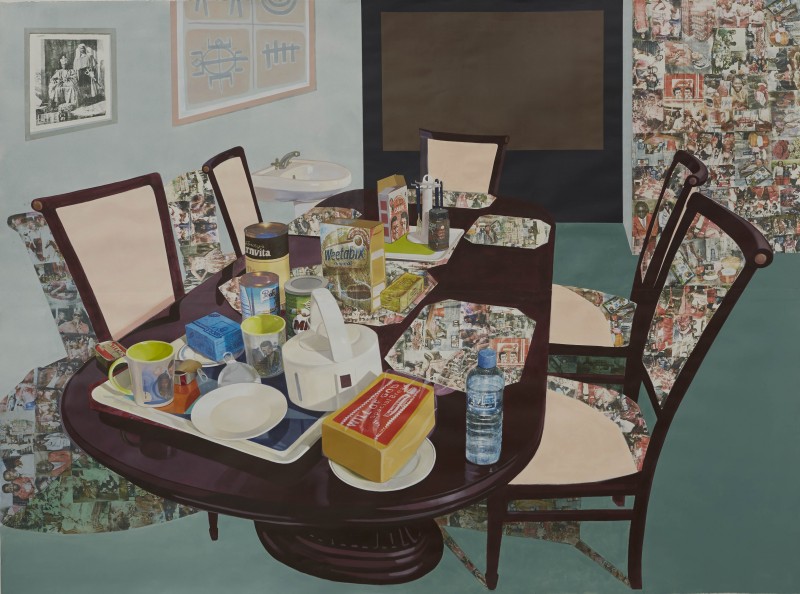

And Akunyili’s Nigerian past? That appears as a rose-tinted collage of colonial-era stamps (Queen Victoria, King George V) and newspaper imagery of Nigerian leaders, pop culture stars, fashionistas and headlines (“Enough Is Enough, Let the Suffering Stop”). The collage spills across a wall, covers the floor and imprints a man’s shirt in her most obviously autobiographical piece, “5 Umbezi Street, New Haven, Enugu,” whose title alludes to Akunyili’s birth in Enugu, Nigeria, and education in New Haven, Conn. Elsewhere it links an interracial couple, tattoos an arm, covers a bed.

While avoiding confessional intimacies, Akunyili manages simultaneously to tell her story and to sketch a larger picture of emigration, dislocation and what she has called the “contradictory loyalties” in her love for Nigeria and her appreciation of Western culture.

We begin to let go, 2013.

We begin to let go, 2013.

About the exhibition:

STEVENSON is pleased to present Kings County, a group exhibition featuring Njideka Akunyili, Meleko Mokgosi, Wangechi Mutu and Paul Mpagi Sepuya.

Today Brooklyn, as Kings County is more commonly known, counts 2.5 million inhabitants, measures 474 square kilometres, and by itself would be the fourth largest city in the United States if it were not part of New York. It traces its roots back to Breuckelen, a 17th century settlement established by the Dutch West India Company, named after a city in the Netherlands. In 1664 the English gained control of the territory, and in 1684 they combined Breuckelen with five other former Dutch towns into Kings County, establishing a political entity which survives to this day.

You lost me, 2013.

You lost me, 2013.

Brooklyn is a place of immigrants, its demographics ever shifting. Complex layers of class are superimposed on both historical and newly established ethnic enclaves. Because everybody who lives there is, in some way, from somewhere else, it has been a theatre of imagination and invention, and Brooklyn as an idea, or a metaphor, has been as important in this process as its physical characteristics. Perhaps as a result, it has attracted an urban creative community of a nature and scale not seen elsewhere in New York – a community that, in turn, has affected the idea of Brooklyn in real and imaginary ways. Brooklyn is often associated with gang violence and artisanal food, but its lived experience is infinitely more complex, and resists such narratives as much as it invites them.

Teatime in New Heaven, 2013.

The term Kings County is unfamiliar to many outside New York, and its archaic, colonial associations suggest an imaginary place. The artists in this exhibition are all, in different ways, invested in this imaginary place, and use the idea of Brooklyn as a backdrop to the making of their art. Nigerian writer Teju Cole, who contributes an essay to the exhibition catalogue, describes Brooklyn, specifically its Fort Greene section, as the only place on the planet where he does not stand out. Moreover, he says that the friendships he has forged in the borough have allowed him to imagine an Africa unburdened by the artificial borders imposed by the Berlin Conference.

Rebranding my love, 2013.

Rebranding my love, 2013.

For Wangechi Mutu Brooklyn was a place to live while getting an education in Manhattan, and now it has become her second home. Meleko Mokgosi was specifically drawn to Sunset Park and its history of manufacturing, as well as its large South American population. Curiously, the other two artists have left the neighbourhood since the exhibition was conceived, or are in the process of leaving. Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Njideka Akunyili are both moving to Los Angeles this year, but often reflect the timbre of Brooklyn social life in their work.

On one level, Kings County is about four immigrants (from Botswana, Kenya, Nigeria and California) in a place of many immigrants. More fundamentally, however, Kings County is about the symbolic potential of geographic locations – about how imaginary places can affect the real world, and vice versa.

Courtesy: Tiwani Contemporary, London.