Njideka Akunyili Crosby, 1983.

Until January 10, 2016.

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

About:

Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s Intimate Work Straddles Mediums And Oceans

The young Nigerian-American artist wins one of the Smithsonian’s most prestigious awards.

By Kirstin Fawcett

SMITHSONIAN.COM

DECEMBER 1, 2014

Since graduating with her master’s degree from Yale University’s School of Art in 2011, Nigerian-born artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby has swiftly gained renown in the New York art world for her large-scale yet intimate figurative portraits and still-life works. They show her American husband, her African family members and occasionally the artist herself engaging in everyday domestic moments—eating dinner, reclining in bed, or having a conversation. The works are a lively amalgam of colors, mediums and influences.

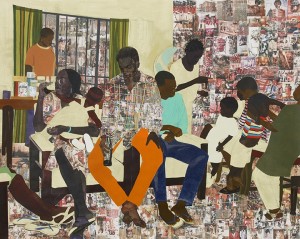

Predecessors, 2013.

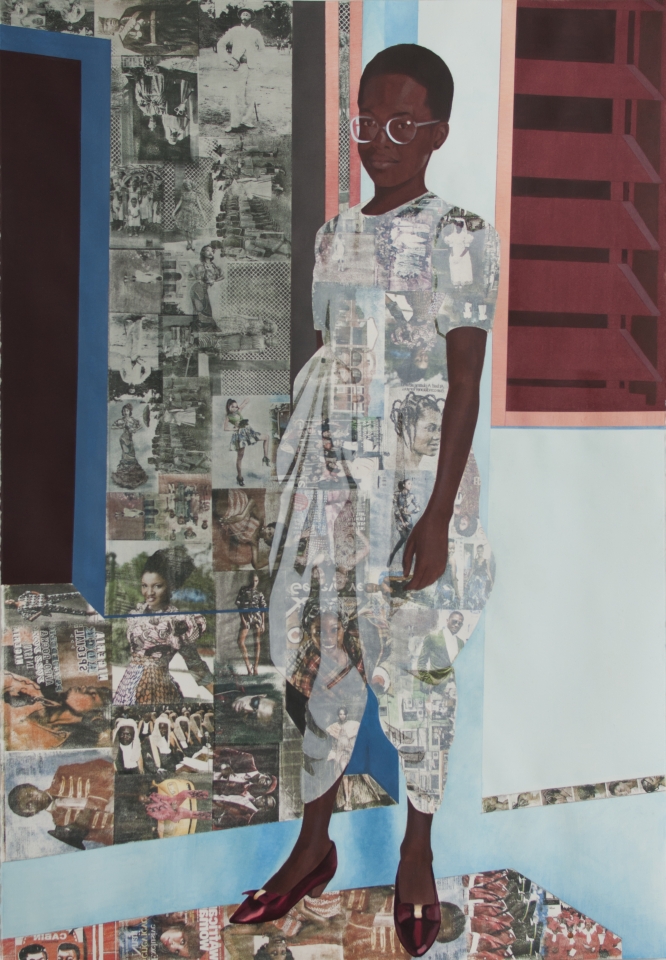

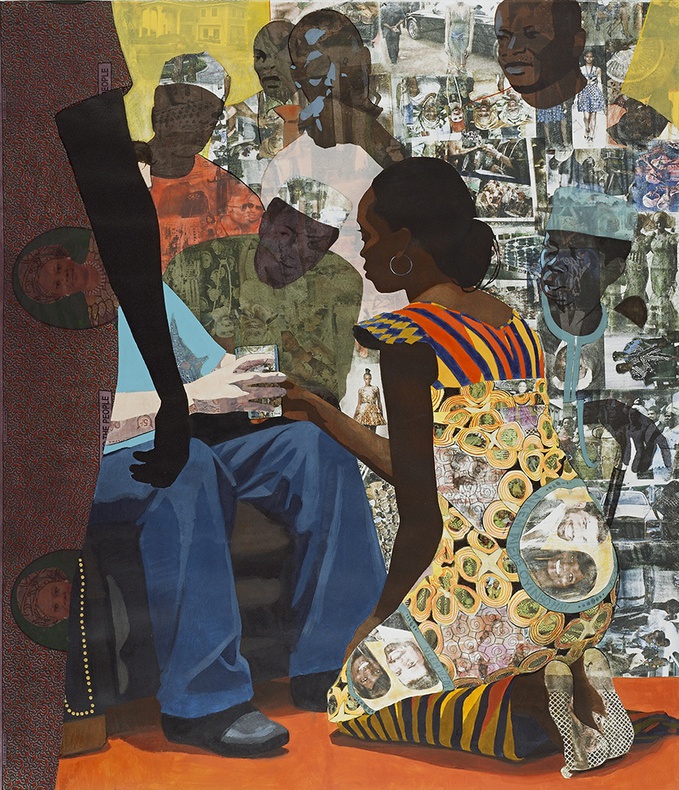

Akunyili Crosby’s personal tableaus are firmly rooted in the classical academic Western painting of her rigorous art school training. However, she puts her own innovative spin on tradition. She works on toned paper and combines charcoal, pastel and pencil drawings with acrylic paints. She then composes scenes derived from her experiences living in both Nigeria and America, incorporating photo-transfers and collages, filled with family snapshots and images taken from Nigerian lifestyle magazines and the Internet. The result? Intricate, textured works that explore a complex topic—the tug she feels between her adopted home in America and her native country.

Something Split and New, 2013.

And now, the 32-year-old artist is the recipient of the prestigious James Dicke Contemporary Artist Prize, a $25,000 award bestowed biannually by the Smithsonian American Art Museum to young artists, who “consistently demonstrate exceptional creativity.” Akunyili Crosby is the 11th to receive the honor and the first figurative painter, says the museum’s curator and Dicke prize administrator Joanna Marsh.

“We’ve had recipients of this award who work in lots of different media, but never someone who’s coming out of a more traditional Western painting legacy,” says Marsh. “I think that’s an important part of both our collection and our focus. It’s wonderful to be able to give the award this year to someone who upholds that tradition.”

Sunday Morning (Predecessors # 3), 2014.

Akunyili Crosby was selected by an independent panel of five jurors—curators, arts, journalists, professors and working artists who were each asked to nominate several artists for the prize. Thirteen other finalists include such art world heavyweights as mixed-media artist Cory Arcangel, and video and performance artist Trisha Baga.

The Beautiful Ones, 2014.

Says juror Harry Philbrick, director of the Museum at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts: “I think it was [Akunyili Crosby’s] internationalism that really jumped out at us and the fact that she produces very sophisticated and beautiful work that is technically accomplished. She’s dealing with issues that are very relevant to us today—tensions between different cultures and different nations.”

Akunyili Crosby first received her post-baccalaureate certificate in painting from the Museum at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts before earning her master’s degree at Yale. Philbrick says he first met Akunyili Crosby in person when he came to view her art at New York City’s Studio Harlem in 2011. Philbrick recalls, he became “impressed with the intelligence and perspective she brings to her work.”

Akunyili Crosby was raised in Lagos, Nigeria, and left Africa at the age of 16 to pursue an education in the United States. The daughter of a surgeon and a pharmacist, she majored in biology at Swarthmore College and intended to eventually become a doctor.

“I grew up in a climate where the options just seemed to be very limited—medicine, engineering, law,” she recalls. Being an artist was not an option. But when she discovered formal art classes, Akunyili Crosby felt “an urgency,” to break away from the preconceived boundaries of what she should do with her life. After a brief sojourn to her native country, where she served in the National Youth Service Corps for a year, she returned to the U.S. to pursue her goal.

Wedding Portrait, 2012.

America would quickly become her second home, especially after a college classmate become her spouse. “I still felt connected to Nigeria, but the longer I stayed in America, the longer I felt connected to it,” she says. “When I started dating my husband, I got to a point where I really began to have a dual allegiance between the countries.”

Meanwhile, Akunyili Crosby’s work was slowly evolving. The disparate mediums, she says, helped her create her own artistic narrative of sorts—one that allows her to fit tiny details, like photo collages from Nigeria, into otherwise conventional household interiors. Combined, the elements use Western portraiture and still life scenes to tell a decidedly non-Western story. The relationships, challenges and new beginnings that underlie intermingling national identities, old worlds and new homes. She also frequently features her husband as a subject, as their marriage is the most prominent symbol she can think of when it comes to the merging of cultures.

“Your eyes are traversing multiple universes,” reflects Akunyili Crosby about her art. “You’re jumping through all these languages of making art, but then you’re also making jumps in continents. It’s this constant shifting and movement across places and time.” (text site Smithsonian)