From the Margins: Lee Krasner and Norman Lewis, 1945-1952.

Jewish Museum New York, till February 1, 2015

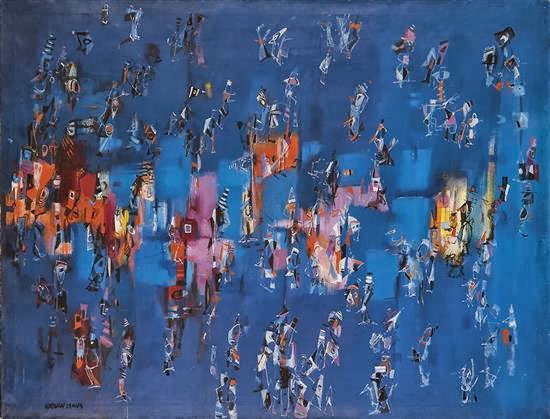

City Night, 1949.

(review in the New York Times)

A Conversation Spoken in Paint

Lee Krasner and Norman Lewis at the Jewish Museum

By KAREN ROSENBERG

SEPT. 11, 2014

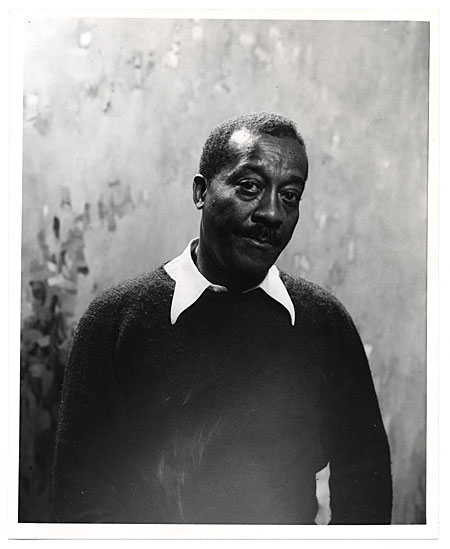

Critics think they have the last word, but sometimes art keeps talking. In 2008, while organizing the Jewish Museum’s boisterous survey of Abstract Expressionism, “Action/Abstraction: Pollock, de Kooning and American Art, 1940-1976,” the curator, Norman L. Kleeblatt, noticed that two paintings — Lee Krasner’s “Untitled” (1948) and Norman Lewis’s “Twilight Sounds” (1947) — seemed to be speaking to each other. He had the good sense to listen and, later, to orchestrate a deeper conversation. The result is “From the Margins: Lee Krasner and Norman Lewis, 1945-1952” a nuanced, sensitive and profound exhibition.

Untitled, 1949.

Untitled, 1949.

The show isn’t really a dialogue, in the conventional sense. But it bravely elides differences of gender, race and religion, finding that Krasner and Lewis — a Jewish woman and an African-American man — shared a visual language that was a subtler, more intimate dialect of Abstract Expressionism. And it does so while recognizing the cultural accents in both artists’ works, the influence of Hebrew writing on Krasner’s grids of glyphs and the connections to jazz in Lewis’s meandering lines.

Probably the most refreshing aspect of the show is the chance to see Krasner matched up with a man who is not her husband, Jackson Pollock. And Lewis, whom curators have too often shown as either a lone visionary or as part of a well-defined circle of black artists, also benefits from the pairing.

Congregration, 1950.

Congregration, 1950.

Building on a section of the 2008 show called “Blind Spots,” “From the Margins” also suggests that Krasner and Lewis were hidden in plain sight: Krasner as the spouse of an art celebrity, Lewis as a black artist whose paintings were more formal than political. (“I’m sure if I do succeed in painting the black experience, I won’t recognize it myself,” he said in a 1968 interview.)

Both Krasner (1908-1984) and Lewis (1909-1979) embraced abstraction in the 1940s, after early flirtations with Social Realism: They both had been involved in the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (and may even have met through that organization), and Lewis had been a member of the Harlem artists’ group 306 (which included the socially minded artists Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence.)

Harlem Turns White, 1955.

Harlem Turns White, 1955.

Some other formative influences are apparent in the show’s first room of paintings: for Krasner, it was the abstract painter and pedagogue Hans Hofmann; for Lewis, the Harlem art school director Augusta Savage. For both, Picasso and Mondrian. Krasner comes across as the more restless of the two painters, moving from the flat, interlocked shapes of “Lavender” (1942) to the dense, peaked brushwork of “Noon” (1947); Lewis seems to hit on his mature scuffed-and-scumbled style without much deliberation.

Even here, though, you can see what Mr. Kleeblatt has called a “magical synergy,” especially in two canvases that feature floating rectangular grids in a palette of reds and mauves.

Twilight Sounds, 1947.

Twilight Sounds, 1947.

More of these moments occur in the second room, the heart of the show, which brings together Krasner’s “Little Image” paintings and the “Little Figure” paintings of Lewis. It suggests not only an obvious common interest in diminutive imagery, but also an obsession with painting-as-writing (or, as the Abstract Expressionist progenitor John Graham called it, “écriture.”)

Untitled, 1957.

Untitled, 1957.

With their neat rows of pictographs, the “Little Image” paintings relate clearly to Krasner’s religious education as a child of Jewish immigrants from Russia. She painted them from right to left, as Hebrew is written. But her glyphs can be read in a broader context, as evidence of a general interest in codes and ancient scripts. (A fascinating catalog essay, by Lisa Saltzman, mentions World War II cryptography and the effort to decipher clay tablets at Knossos as possible influences.)

Lewis’s “Little Figure” paintings can appear similarly impenetrable, with their bluesy palettes and jazzy noodlings. (Some, like “Magenta Haze,” make explicit reference to music.) Like Krasner’s “Little Image” paintings, they eschew the big, swashbuckling gestures of textbook Abstract Expressionism in favor of a wiry sgraffito (or occasionally, in Krasner’s case, a thin and tightly controlled drip).

Scale matters, too: These are intimate paintings, made in small, domestic spaces. (Krasner worked in the upstairs bedroom of the house she shared with Pollock in Springs, a bucolic East Hampton community; Lewis in his apartment on 125th Street.) And they come in very un-Abstract-Expressionist shapes and proportions: long, vertical canvases that resemble Asian scrolls, and even a tondo.

The homeyness of their work is reinforced by the installation, with such midcentury touches as mint green walls and Eames chairs in the museum’s wood-paneled second-floor galleries. (“Action/Abstraction,” by contrast, informed by the pronouncements of Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, was shown in the museum’s white-box ground-floor space.)

In the final gallery, which goes beyond the dates in the show’s title to accommodate a couple of works made in the 1960s, both artists do experiment with bigger canvases and brighter palettes. Krasner’s “Kufic” (1965) unleashes sweeping golden brush strokes, reminiscent of Arabic script, on a straw-hued ground. And Lewis’s “Alabama II” (1969) deploys a small, barely visible line of marching stick figures on a searing expanse of sunset pink, hinting at the struggle for civil rights while still insisting on being read as an abstract painting.

The show’s organizers (Mr. Kleeblatt, the museum’s chief curator, with an assistant curator, Stephen Brown) finish with a short audio program, which weaves together snippets of interviews with Krasner and Lewis. It’s an appropriate way to end “From the Margins,” an exemplary show that says to curators everywhere, keep listening.