After the 1958 race riots, there was an effort to heal the rift between the black and white communities. From that intention, those immigrants from Trinidad, St Lucia, Jamaica and other countries established the Carnival, bringing through the influences and flair from back home. The first Carnival was held on 30th January 1959 in St Pancras Town Hall under the organisation of political activist Claudia Jones. Jones founded The West Indian Gazette, the UK’s first black newspaper, and the carnival was televised by the BBC in an aid to build bridges in Britain.

Christabel Johanson: How Notting Hill Carnival was meant to heal the rift between the black and white communities

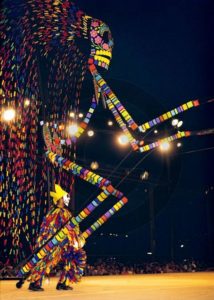

Carnival costume designed by Peter Minshall

The Notting Hill Carnival

Past and Present

The Notting Hill Carnival has been a highlight of London’s summer calendar for as long as many people recall and this year will be no exception. As the city heats up, August marks the celebration of diversity and West Indian culture once more. The flamboyant parade engulfs Notting Hill, Westbourne Park and nearby neighbourhoods. Ironically these areas in London are nowadays rather affluent. However behind the glitz and glamour we know of today, there is a very important history behind the “how” and “why” the carnival began, a far world away from contemporary gentrified Notting Hill. However the motives that established the carnival are still as relevant today as they were decades ago.

Notting Hill Carnaval

To talk about the carnival we must first go further back in time to 1948 when 500 or so Caribbean people sailed on the Empire Windrush to begin regenerating a war-torn Britain. Their story of struggle and success is one that is intrinsically linked to the Carnival. Those immigrants believed they were equal members of the British Empire, coming to the UK from the colonies to bring new life into the country they loved. Back in the Caribbean the Queen’s picture was on classroom walls, people sang our national anthem, literacy levels were high and as far as families were concerned they were on equal status with white British citizens. England was their spiritual homeland and they were loyal to the Empire.

However when they arrived, the harsh reality was anything but a dream. West Indian migrants were met with racism, disdain and hatred. This rude awakening was made even worse by the fact that those black families had been well-educated and knew so much about Britain, compared to the ignorance of the white Britons who had little concept of Jamaica and other islands, believing they were living in trees and were a lower caste than them. The reality was simple: to be British you had to be white.

*

Tensions continued to mount for years with more black immigrants settling in areas like Brixton and Notting Hill. At the time working-class white people felt the brunt of this settlement even harder, believing that the competition for jobs and housing was due to the influx of these immigrants. Colonies in the Caribbean and Africa at this time were also pushing for independence which increased racial tension. White gangs and nationalist groups were exacerbating problems on the ground and although black communities were warning the authorities that trouble was brewing, no action was taken. Then after a week of skirmishes and smaller vandalism, on 30th August 1958 a group of 400 white youth began attacking black populations in Notting Hill. Petrol bombs, milk bottles and weapons were used against the community, who retaliated in self-defence. The riots went on for a week and resulted in 140 arrests, mainly of white men.

Malcolm X with the West Indian Gazette. Claudio Jones on the front page. Copyright/Photo courtesy londonsocialisthistorians.blogspot.com

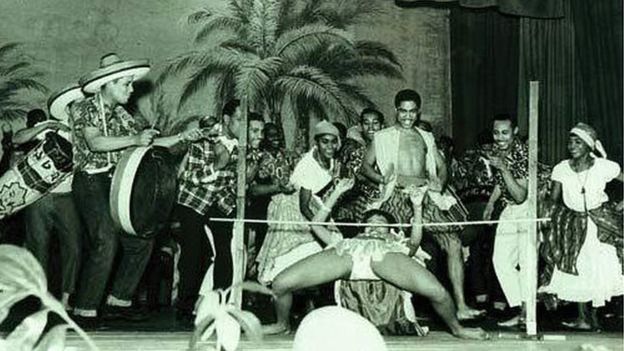

After the 1958 race riots, there was an effort to heal the rift between the black and white communities. From that intention, those immigrants from Trinidad, St Lucia, Jamaica and other countries established the Carnival, bringing through the influences and flair from back home. The first Carnival was held on 30th January 1959 in St Pancras Town Hall under the organisation of political activist Claudia Jones. Jones founded The West Indian Gazette, the UK’s first black newspaper, and the carnival was televised by the BBC in an aid to build bridges in Britain. Pearl and Edric Connor are also credited with organising and booking many of the artists and events in the early days.

St Pancras Town Hall

The event became a regular on the annual calendar, and then eventually in 1964 Rhaune Leslett led the way for the celebrations to go outdoors. As part of the promotion, musicians such as saxophonists played in the streets of Portobello Road to garner interest from the locals. This built anticipation within the community. This community was not only the black population anymore, but extended to other demographics that shared the tough conditions of the time. These were the Irish, the working-class, the Africans, Indians, Cypriots, and the poorer families that were all struggling in congested areas where tensions could and had previously rose to fever-pitch.

Notting Hill Carnival

As the carnival continued, the pageantry of West Indian carnivals (such as Trinidad’s) inspired the look of the event. Peter Minshall created a lot of the costumes that have now become one of the iconic features of the event. But it was Leslett’s vision of a celebration bringing all races and backgrounds together that became the enduring motive of the carnival. Steel pan musician Russell Henderson was invited to perform, and the familiar sounds of the Caribbean wafted through the streets of Notting Hill attracting revellers and became the first Notting Hill parade. Word spread across England about the parade, drawing more participants every year.

*

As the carnival evolved, sound systems became static with stages, performers and DJs eventually manning more than the 38 sound stages which now exist. Some mainstays include DJ Norman Jay’s Good Times stage. The music and the spirit of counterculture has attracted other sub-cultures such as punks in the 1980s, or international acts such as musician Wyclef Jean or mainstream radio DJs like Annie Mac.

Notting Hill Carnival Soundsystem, 1981

On 22nd June 2018 the UK celebrated the 70th anniversary of Windrush Day and undoubtedly this will be a milestone year for the carnival in light of these celebrations. As the biggest street festival in Europe the carnival has been a platform to celebrate but also discuss important narratives in Britain. For example the carnival has always had a political awareness of racism and other cultural issues. This year undoubtedly the collective consciousness will be thinking of the Grenfell disaster.

In recent years the carnival has been attached to violence and knife crime. However it is important to remember the true essence of the carnival away from the propaganda. To this end, carnival pioneer Carl Gabriel sheds light on his involvement and experience of the carnival.

Tell us more about yourself.

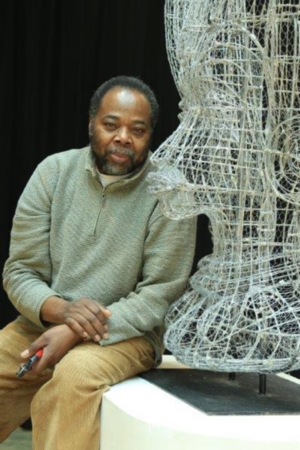

My name is Carl Gabriel and I work with my wife Lynette as 3D traditional Carnival Artist. We started contributing artwork to Notting Hill Carnival in 1994 and continue to do so. We got into the Carnival Arts side by starting a carnival mas band by the name of “Misty”, with the main aim of promoting traditional carnival skills, and to pass on those skills to the youths.

Carl Gabriel

Who has influenced your work?

As the lead artist for Misty carnival band, my aim was to produce unique works and not to be influenced by anyone, having said that a designer/band leader called George Bailey comes to mind as someone who’s inspired me. We have never met but the stories we are told makes us feel a connection.

How important is the carnival for representing black identity?

The carnival is important in representing black identity in Britain, but we must maintain the traditional elements in carnival. Our artwork connects to black identity by drawing from a mixture of today’s lifestyle and traditional ways, and inspiration is drawn from ancient African cultures.

What are some of the highlights of your career?

Some of the highlights of my carnival career were when my band was commissioned to curate the carnival exhibition and parade in the Victoria & Albert Museum and to exhibit and run family workshops in the Science Museum around the same time.

Why is the Notting Hill Carnival so important?

It is important that carnival is promoted as a cultural event rather than a massive street party. In my opinion Britain has not embraced carnival as part of its tradition because of the negative and not enough positive press in the past.

What advice would you give to Britain’s next artists?

My advice to the next generation of artist is to be original and be true to your work. My next project is will be one of my most ambitious so far it will consist of seven heads depicting ancestor and will stand 3.5 metres when completed.

*

For nearly 60 years the Notting Hill Carnival has come out year and year again; rain or shine to wow crowds. The carnival queens and kings never fail to disappoint tourists and locals alike and it is a brilliant platform to showcase traditional Caribbean influences like Soca music, steel pans, custom-made floats and entertaining sound systems littered across the site. West Indian street food like jerk chicken, rice & peas and drinks are just one way in which everyone can enjoy a bite of West Indian culture. In fact 15,000 fried plantains, 1 tonne of rice and peas, and 10,000 litres of Jamaican stout are consumed every year.

*

Despite the headlines in recent years, as Carl points out, the media are still in part responsible for focusing on the negatives rather than the successes of the parade and the spirit of unity that the carnival was borne from. More importantly, it is easy to fool ourselves into thinking we are living in a post-racist world. However the tragedy of Grenfell or the Windrush scandal proves that there are inequalities in society that are still being played out; whether spurred on by race or class, the tensions that Claudia Jones and other pioneers were motivated to fight still exist in 2018. Let’s remember this as we step onto the streets of Notting Hill to celebrate this year. Carnival is not just a street party, it is a cultural event and a movement in unity.