On July 9, editor Rob Perrée and I decided to take a trip together, separately. Rob was home in Amsterdam; I was in Paris. It occurred to us that we might not be in the same city during the summer, so we decided to rectify that by buying train tickets to meet in Brussels — a city geographically in the middle, and one rich in things to see for those of us interested in African art. Moving between cities and countries in pursuit of cultural knowledge, Rob and I chose to participate in the “Afropolitan Age”, a concept central to the two major exhibitions on view in Belgium that inspired us to go on the road in the first place.

Shelley Rice on the exhibitions incarNations: African Art as Philosophy and Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age

On the Road: Africa in Brussels (with Rob and Shelley)

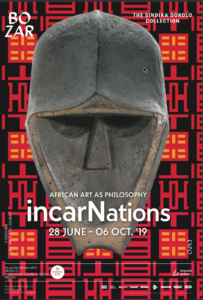

Rather than a review, this essay is a series of ruminations about what I learned from seeing the work of young artists, collectors and curators committed to reassessing and understanding the cultural productions of Africa and Africans. The splendid exhibition at Bozar – a collaboration between collector Sindika Dokol and artist Kendell Geers – has as its title incarNations: African Art as Philosophy; and the entire display is dedicated, not only to showing masterworks from Africa and its Diaspora, old and new, but also to using the exhibition format as a mode of interpretation and communication. As a viewer, I felt that the experiences of both the Bozar show and Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, curated by Sandrine Colard and shown at WIELS, were exploratory, as if the curators saw the exhibitions as an opportunity to make statements that were inclusive, global and revisionist rather than simply aesthetic. Attempts to visualize the unique trajectory and expressive culture of a continent, these shows made proposals far beyond formalism – and geographical borders.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Landlord, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Harry G. David Filothei, Tiwani Gallery, London

I’ll start with Multiple Transmissions, which (in the curator’s words) highlights former artists-in residence at WIELS whose practices “weave tangible and imaginary geographies.” The eight contemporary African artists involved – Georges Senga, Simnikiwe Buhlungu, Sinzo AAnza, Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Jean Katambayi, Nelson Makengo, Pélagie Gbaguidi and Emeka Ogboh – partake of the transnational cultures of the 21st century; mobile and urbane, they are rooted in African but have “become successive locals of multiple places and cities,” and their works flourish in cosmopolitan soil. The curator sees these “multiple transmissions” of artistic traditions as an important evolution in contemporary African expression. The new “itinerances,” according to Colard, have shaped individual artists whose expanded mental geographies transcend borders and media. Sweeping aside ossified notions of authenticity, tradition and identity, “Afropolitanism” inevitably gives rise to “transversal artistic legacies and global resonances,” incarnations of Okwui Enwezor’s “post-colonial constellation.”

The works on view were a mixed bag, and were extremely diverse in country of origin, media and themes. A number of them, however, focused on the life and energy, the sounds and images, of major cities. Certain themes recur: mobility, electricity, technology and noise especially. Nelson Makengo’s experience of night time in Paris and Kinshasa – and his understanding of the social and political ramifications of electricity or the lack thereof – gave rise to films and multi-media installations paying homage to the citizens whose self-illuminations reflect the “precariousness and social chaos” of Kinshasa. Inspired by both Russian and African artists as well as his European sejours, Makengo uses his international references and experiences to shape a complex and nuanced vision of his home town. Jean Katambayi’s Afrolampes also focus on the light (or lack thereof) in the Congo; drawings of phantasmagorical light bulbs visualize the “black light” transmitted by electrical infrastructures neglected and dismantled. Katambayi’s Voyant, an oversized, comic transformer-like figure, was inspired by the robots regulating traffic in Congolese cities.

Emeka Ogboh, Spirit and Matter, 2017-2018. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Imane Farès, Paris.

Emekah Ogboh focuses on the noise of Lagos, on the loud and emphatic announcements of bus drivers, and on the bus station as a point of convergence and passage (both physical and spiritual) in city life; Georges Senga’s photographs visualize the “traffic” and the international communication networks of cinema – posters, theaters, DVDs – as they have evolved in his hometown of Lubumbashi. Simnikiwe Buhlungu’s videos are about “stereomodernism,” the echo of sounds, words and ideas that move between Africa and its diasporas in cultural exchanges across the Black Atlantic; while Sinzo Aanza’s photographs, installation and film theatrically mock political power and its violence, and examine how capitalism has robbed the Congo’s people of their resources, forcing them into exile and destroying notions of citizenship, the nation-state and sovereignty. Moving away from African cities and focusing instead on the connections between European art and the African experience, both Pélagie Gbaguidi and Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum appropriate and problematize the icons of the Western imaginary. Gbaguidi created beautiful textiles in Italy radically questioning and reconfiguring the archetype of the Christian Madonna; and Sunstrum’s painted portraits, with faceless models in fantastical environments freely mixing historical and contemporary African and European iconographies, landscapes, furnishings and fashions, embody both the paradoxes and the pleasures of the “multiple transmissions” the curator of the exhibition intended to describe.

Installation views incarNations, 2019

Some of these works were better than others, but as Colard stated all of them had a common thread: every one of the artists shown had the goal of placing Africa, Africans and African life within the broader context of modernity, mobility and urbanity. Every one of the artists rejects the stereotypic image of African art as traditional, primitive and timeless, preferring instead to emphasize the complex nature of life on the continent in the 21st century, when styles, customs and identities are constantly disrupted by new and evolving global circumstances. Though very different in its aims and presentation, incarNations: African Art as Philosophy shares the same ambitious goal as Multiple Transmission. It too seeks to question, understand and redefine the nature of a continent’s expression, as it moves through time, space and the Black Atlantic.

There are a few things to mention first and foremost. incarNations was designed to visualize Senghor’s idea that the art of Africa is the philosophic statement of a continent and a people, and not simply a decorative proposition. For Dokol and Geers, the meaning of the works on view, many of them famous, goes way beyond the aesthetic – and had little to do with the judgments and market of the Western art world. It was born of history, of philosophy, of religion, emotion and experience, and the rhythms of its forms – whether traditional or avant-garde – are the expressions of a people, whether they live in the past or present, in Africa or its diaspora. In order to make this point, the curators have mixed and mingled objects from diverse times and places in an unconventional installation: organized in discrete sections, distinguished by wall patterns and mirrors that embed art works in an immersive environment and frame viewers’ experience of the show.

Installation views, incarNations, 2019

The curators describe this experience as “Afrocentric,” grounded in every room by classic African sculptures – or, using Congo terminology, “force objects” embodying powerful spirits. “We do not stare at the sculptures as Western ethnologists,” they write in the Visitor Guide, “but place African masks onto our faces in order to physically experience the spiritual trip.” Seeing the mirrors on the walls as central to the meaning of the exhibition, they claim that it “reminds us that looking at art is not a passive deed, but an active participation in the artist’s imagination – and that behind each mask, painting or sculpture, was a person who transformed (his/her) spirit into matter for the visitor to behold. Look past the mirror reflecting your image and imagine seeing the world from the other side of the mask.”

This message — that artistic displays can be a form of experiential knowledge, linking people to each other – gained power from both the installation and the incredible strength of Dokolo’s collection. Beginning with traditional African art, he branched out and started a new collection of contemporary work. Soon after, he realized that, as he said in an interview published in the (excellent) catalog, “I have only one collection and only one way of approaching art…It’s an African perspective on art, rather than a way of looking at African art.” Thus was born the “philosophy” of African art so beautifully embodied in the exhibition, that there is a continuum – emotional, spiritual, formal – between all works created by Africans, no matter where, no matter when. In this context, minkisi (Congolese force objects) with mirrors on their stomach or in their eyes are placed in dialogue with self-portrait works by Adrian Piper and Santu Mofokeng. There are rooms privileging African masks (paired with photos by Phyllis Galembo and Andres Serrano), masquerades or tricksters (Hank Willis Thomas). Works by Sue Williamson and Otobong Nkanga communicate across the centuries with traditional figures of maternity and female power. Combs and crucifixes, primordial couples and political power, relics and magic are visualized, then and now; even cultural appropriation is raised as an issue, in the last room where a recent bronze Ife Head (Male) by Damien Hirst (part of Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable) is placed in the middle of a powerful arrangement of traditional sculptures from different regions on the African continent. As meanings and correspondences ricochet across the rooms, contemporary ideas are echoed in history – and the viewer’s image, always central, is reflected in mirrors that telescope both time and space.

Installation view incarNations, 2019

It is perhaps not surprising that the curators of incarNations: African Art as Philosophy wrote in the Visitor Guide that “the energy in the exhibition is that of an African metropolis.” Like Sandrine Colard, Sindika Dokolo and Kendell Geers clearly see the African city as a crossroad — a passage between continents and centuries, cultures and races, histories and religions. And in their telling of the story, as in hers, the continent’s art – made at home or in diaspora — is the expression of that complexity, translating into form the rhythms, diversity and contradictions of life on earth. For these three curators, the philosophy of African art (whether traditional or avant-garde) transcends discrete time periods, cultural customs, politics and geographical borders. Vehicles of spirit and repositories of profound emotions, these objects embody a world view whose aim is to shatter boundaries and synthesize “multiple transmissions.”