Aryan Kaganof, an independent filmmaker, novelist and a reluctant poet, filmed a three part film, ‘Opening Stellenbosch: From Assimilation to Occupation’ to document the struggle of the students at the University. This was done while he was an artist-in-residency at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (the institute later refused for Kaganof to screen the film at the department).

Zimasa Mpemnyama reviews the latest documentary of Aryan Kaganof.

Opening Stellenbosch: From Assimilation to Occupation by Aryan Kaganof*

After Cape Town, Stellenbosch is the second oldest European settlement in the Western Cape. Much of the architecture and ethos of the Cape Dutch is still preserved in the town. It is celebrated as a wine town because of the vast wine farms and vineyards in the area, but what is less known, intentionally or otherwise, is its slave history and that it is the place where apartheid was intellectually engineered.

Colonial peace at Stellenbosch University, along with the University of Cape Town, Rhodes University, Wits University, University of Johannesburg and others, was disturbed late last year by radical protest action from black students tired of a colonized and exclusionary higher education system.

Aryan Kaganof.

Black students at Stellenbosch University collectively met under the banner of Open Stellenbosch (OS) to discuss and tackle some of the issues causing them estrangement at the institution. OS sprang to life during the time of the deliberations to remove the Cecil John Rhodes statue at the University of Cape Town. A time when discussions about historical black pain and slavery (and what the ramifications of slavery today are) were on the table, tackled by radical student movements around the country.

Opening Stellenbosch, still, 2016.

Aryan Kaganof, an independent filmmaker, novelist and a reluctant poet, filmed a three part film, ‘Opening Stellenbosch: From Assimilation to Occupation’ to document the struggle of the students at the University. This was done while he was an artist-in-residency at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (the institute later refused for Kaganof to screen the film at the department).

Part one interrogates the place and relevance (if any) of white ‘allies’ in the black struggle. Part two finds the students of OS interrogating Stellenbosch University as a space alien to them through the language policy, while part three looks into rape culture, intersectionality and the feminist movement on the campus.

Opening Stellenbosch, still, 2016.

Kaganof’s technique has been praised (and critiqued) because of its radical re-imagination of the process of filmmaking. A technique regarded as avant-garde by some. In ‘Opening Stellenbosch’ he moves between quick sequences and long individual dialogues. He uses jump cuts, multiple layering, and long silent scenes filmed camcorder style, as is the case with his previous student centered documentary ‘Decolon i sing Wits’ (a film which also caused a stir during its initial screening at Wits University where Kaganof was a visiting lecturer in 2014).

Decolon i sing Wits, still, 2014.

‘Opening Stellenbosch’ (and I argue Kaganof’s style of filmmaking) forces us to question white supremacy and capitalism and how these isms inscribe ways of thinking and doing. The film subverts mainstream ways of filmmaking. It’s not clean and crisp but scattered. Unconfined. It is purposefully not packaged for mass consumption – but for critical reflection. This is achieved by carefully choosing different camera angles, choosing the right people to interview and making sure the placement and sequences of these interviews/dialogues speak to (and of) each other. The use (or disuse) of color is also used to ascribe meaning and depth to certain images.

Opening Stellenbosch, still, 2016.

Aryan Kaganof works the camera in an almost casual fashion and is present at the most delicate moments. This creates an interactive experience, placing the viewer at the center of the action.

In the opening scenes of the first part, ‘The White Allies’, we see shadows of wooden funeral crosses shown in black and white. Each cross has a name written on white paper stuck on it. These are the names of the 34 miners whose death beds were the red dust and soil at the koppies of Marikana in 2012. The crosses and names are then superimposed with a faint video of the state police stalking and killing the miners. In these first images, the stinging memory of the shooting is reawakened.

*

Equally, part two of the documentary, ‘In Privileged Spaces’, starts in the same painful vein, with a moment where OS students disrupt a class. One black student stands up in the middle of a lecture and says, “I can’t breathe in this lecture because my education is colonized.” A few seconds after, about 25 students start chanting “I can’t breathe” repeatedly. Then, a tall, blonde, white male student gallops towards the front of the lecture – action hero style imbued with a strong sense of white masculinist arrogance. He speaks through the lecturer’s mic while showing the protesters the door, as if shooing livestock, “excuse me, we actually have a class, can you go away,” he says.

*

The film is honest. The black student movement is not entirely united. Voices are not in unison when discussing gender, sexuality, or even race. There is a constant grappling with ideas and practise. There are moderates and radicals. Those who want slight changes in current policies (just enough to make life bearable) and those who want to burn down colonial structures. This unevenness in opinion becomes glaring in part one where Kaganof cleverly critiques the role of white ‘allies’ in the black struggle. He does this by focusing on a white, female lecturer who says she was at the forefront of starting the first dialogues that gave birth to the OS movement.

In this moment, it seems Kaganof positions himself as the white ‘radical’ that problematizes the status quo and his fellow whites by questioning white culpability and supremacy. But we must all ask what differentiates the white conservative racist, white liberal and the white radical?

*

The white lecturer insists that she also feels pain at (black) injustice. A white student admits she “doesn’t understand” but she wants to fight oppression, alongside black students. As the white ‘allies’ speak I am reminded of a film about slavery in America by Danish film director and screenwriter, Lars von Trier titled ‘Manderlay’. In the film, a white woman, Grace, passes a town – Manderlay – and is appalled by the fact that, despite the abolision of slavery 70 year prior, black people still live as slaves in the town. Determined to free the blacks, she stays and works with the slaves to liberate them. Grace sees herself as a ‘liberator’ but she ends up taking up the role of the slave master, even whipping one of the black male slaves in the end.

*

In a talk about the movie titled, ‘The Lady with the Whip’, cultural theorist Frank Wilderson III says about the movie, “By removing the white male from the traditional role of protagonist and master, ‘Manderlay’ invites us to think of slavery as a relation of power between those who are ontologically dead, and those who are ontologically alive.”

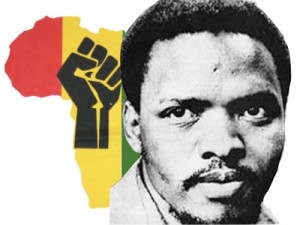

Wilderson then, along with Steve Biko’s scathing critique of white liberals (which is shown on screen as the white lecturer speaks) invites us to interrogate power dynamics within black-white spaces. They both ultimately come to the conclusion that the presence of whites and whiteness in black radical spaces sucks into invisibility any possibility of black liberation in those spaces.

Conversations around decolonization in South Africa have forced all fields (including film) to (re)think the ways in which images mean. It has also forced a conversation about the people who generate these images, for whom they generate them, for what purpose and the implications of them. Kaganof’s positionality as white male means that his images generate him a certain currency and agency in progressive spaces. Although he may or may not accumulate wealth from the images, he does accumulate social capital (and in a way lands up in almost the same position as the white liberal he critiques) by using images of black radical protesters at their most fragile moments.

*

Watching OS is painful. Not because of the unorthodox (but beautiful) way in which it is made but because one can sense the discomfort in the student’s faces. Black faces that twist and distort trying to find solutions to a problem they did not create.

The world premiere of ‘Opening Stellenbosch’ was recently in Milan during the 26th festival of African Cinema.