Oupa Sibeko and Nicola Pilkington: The Rebirth of IQHAWE

About the artist:

1. Oupa Sibeko is an interdisciplinary performance artist, scholar and educator whose work deals with matter and politics of the body as a site of contested knowledge. Last year, Sibeko was named as one of the Mail & Guardian’s Top 200 Young South Africans; recipient of the David Koloane award and Hendrik Grohs top 20 artists of the year. And he has been touring Europe with the experimental opera ‘Pygmalion/ L’Amour et Psyché’, choreographed by the incomparable Robyn Orlin.Sibeko has closely collaborated with the likes of Albert Ibokwe Khoza, Fana Tshabalala and Benjamin Skinner, exhibiting his around South Africa at the RMB Turbine Art Fair, Spier Light Art, The State Theatre, The National Art Gallery of Namibia, Infecting the City, The Cape Town Holocaust & Genocide Centre, The Freezer in Iceland and more. Sibeko’s most recent interrogations explore the ocean as a site of trauma, longing and resistance in ‘The Inland Sea’ and ‘Black is Blue’. Both performances are meditations on play, using improvisation and make-believe as modes of survival and ways in which people have historically recreated cultures through embodied, reflexive, and collaborative ways.

About the project:

2.

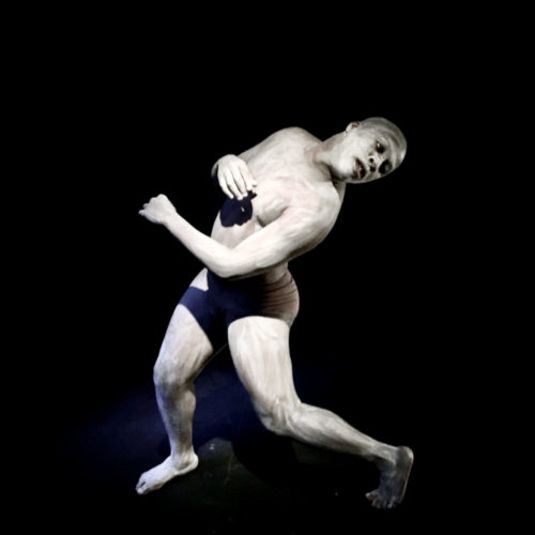

The Rebirth of Iqhawe is a short experimental dance film, exploring the potential to hybridise Sibeko’s Butoh-inspired performance practice into the film form: fragmenting, collaging and refiguring the body in time and space as a means to capture the corporeal expression of the movement. While by the modern Japanese movement practice of Butoh explores the connection of the body to mind and soul; the film attempts to channel the kinaesthetic energy of the body through the lens, the cut and the screen’s ability to bend time and space. The film is a direct response to Reeds of Iqhawe, Sibeko’s performance art and photographic series, exploring the body and its capacity for the sacred and the socio-political. By drawing on his seSotho ancestry and the Butoh movement practice, Iqhawe investigates the possibility of ceremonial and aesthetic fusion. Rebirth of Iqhawe premiered as part of an installation at the Wits Art Museum in 2017 and has been screened at film festivals around the globe, including the International Video Art House Festival in Madrid; Instants Vidéo Numériques et poétiques in Marseille; and the 6th International Meeting on Videodance and Videoperformance.

About the project:

2.

The sacred act of creation is repeated through a person’s lifetime. We are born. And, this act becomes a preoccupation of our rites and myths. Jesus, Buddha, uNomkhumbulwane, Modimo le Badimo sit or stand as figures that remind us of the cycles of creation. Creation itself becomes our biggest spiritual lesson. We learn that the capacity to create and recreate is sacred, as we mark different points of our lives. This we do whether we ascribe to any religion, spiritual belief, or not. Rebirthing ourselves is what we do when we learn and grow.

Oupa Sibeko shape-shifts in slow time, through the short meditation of The Rebirth of Iqhawe. A hero, reborn. The work asks us to sit with the thought of recreation and the work of becoming a hero; not as a simple act of birth into knowing, but as a constant repetition of the process of self-creation. It is a meditation on man. The Butoh aesthetic of the clay-painted body, resonates strongly with the South African image of male initiation rituals. Painted in full body colours of white or red, male initiation rituals rebirth the body of a child into man. But, of course here, it is the rebirth of a hero that we ruminate on.

Without the burdened social notions of a hero, we zoom into the close-up image of a body. A belly button, some hair, ankle, fingers, chin, a scar, a pimple covered in a thin layer of paint. These mere body parts have a sense of fragility in the extreme close-up. Just parts that come together to create a body. Just a body reformulating itself as though at birth. An allowance of the death of an egg to recreate a new egg. A new entity becomes possible altogether. In the blue waters of the film’s grading and the deep-sea dive of swimming in the music of the mechanical sound of wading, is an opening to a different space of thinking. A portal is created and recreated with the repetitions of watching a hand crush an egg and reversing the action to wholeness again. The triad of images create tableaus, of meditative possibility.

Before you stack meaning onto the work, there is an invitation to breathe and be in a process unfolding. Sibeko, folds his full body in different postures. Opening and closing. Like a nestling discovering its own creation, he contorts in Butoh-inspired poses. Looking up and out, looking in, reaching and closing, he reshapes and reforms himself as though testing the possibilities of his body’s existence. He spreads his arms like wide-open wings, not for the active impulse of flight but to test their full length. He stands on one shaky leg and repositions himself with one leg bent and the other straightened. He puts his hands on his head like antenna or horns, as though uncertain of his nature. The potential for any posture to be assumed is then contrasted with the final upright image, which is so final in its simplicity that it attests to the ways in which our upright evolutionary stance takes for granted that we could play ourselves out in so many ways, other than just this one. We need only sit to meditate on our beings, see ourselves so closely that we let go of all the noise of how we should be. We see our potential to be different. Perhaps this is how we can rebirth ourselves as heroes again and again. Recreating the notion of a hero itself, The Rebirth of Iqhawe meditates on the awakening of a new man.