“Pangaea II draws on works from two vast continents tormented by their own grievances. Sculptural and two-dimensional, that when juxtaposed boil down to the visual exuberance of Latin American, that sugar-coat the causal effects of colonialism, consumerism, and political and social unrest, with unbridled adolescence. And more significantly the constellation of countries in Africa, from where art appears to function as a placebo for the chronic ills of a continent damaged by civil war, starvation, and slavery. All of which makes for a show that is as much about what is behind the curtain, as what is visually present.”

Rajesh Punj on ‘Pangaea II’ in the Saatchi Gallery in London.

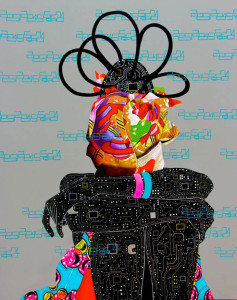

Eddy llunga Kamuanga, Elongated Head, 2014.

Pangaea II: New Art from Africa and Latin America

Unruly Beings

Back in October 2014 during the autumn fizz of Frieze Art Fair, on the other side of the city, collector Theo Danjuma politely hijacked a beautiful five storey Victorian house, and choreographed a cannon of contemporary artworks. Floor and wall pieces by artists born and based in the African continent; with those who had subsequently migrated to Norway or to the United States. And in context such an inspired accumulation of contemporary works made for an arousing chorus of art from Africa. Recalling some of those playful and political works, one enters Saatchi’s cathedral like setting and wishes for the same kind of bravado to champion over the imagination. As Africa is juxtaposed against Latin America in a Pangaean composition of continents. And as is always the way with the gallery’s uncompromising simplicity, one is gifted with works that are for the majority impressive. Pangaea II: New Art from Africa and Latin America reads like a geography lesson, that might well nourish an audience with a taste of Africa and the Americas; and in content neatly follows on from part one.

Jean-François Boclé, Everything must go, 2014.

Jean-François Boclé, Everything must go, 2014.

Highlights include Paris based, Martinique born Jean-Franҫois Boclé’s plastic bag installation Tout doit disparaître!/Everything Must Go (2014), which is testament to an incredibly beautiful aesthetic; industrial in scale. Depositing some 97,000 clinically coloured plastic bags into an elongated carpet like setting, Boclé’s work reads as much like a theatrical seascape, as it might appear as a monument to consumerism. The intense disarray of thousands of plastic bags tightly pressed one upon another proves hauntingly attractive, for the artist’s perfection for moulding this emerging submarine styled shape onto the floor of the gallery. As the intoxicating blue appears to positively draw an audience into the first gallery. Conjuring one’s perverse pleasure into wanting to physically lay down on the work, and effectively becoming entirely consumed by thousands of agents of consumerism. Such desired intervention though is a distraction from the greater politics of Boclé’s practice. As he is preoccupied with the burden of capitalism and post-colonial history. As they serve as narratives for the basis of his work. Tout doit disparaître!/Everything Must Go is a playful but incredibly poignant homage to the lives lost at sea during the transatlantic slave trade. And in magnifying a disposable plastic bag by sheer numbers, Boclé appears to want to draw attention to the complexities of modern history. As the connotations of consumption and exchange become the sub-plots from which he understands the original ills of colonialism.

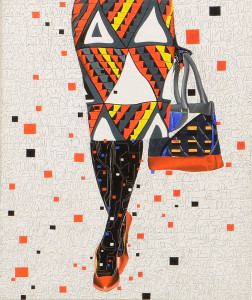

Eddy llunga Kamuanga, Untitled, 2014.

Congolian Eddy llunga Kamuanga’s canvas Sans Titre/Untitled (2014) has an advertiser’s energy about it. As he details the lower half of a woman in contemporary dress, clasping a matching handbag. For Kamuanga the pattern of the model’s skirt and accompanying handbag become the overriding template for the rest of the work. As with one eye to Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, Kamuanga lifts the coloured squares from the skirt and repositions them onto the background. And in so doing the painting becomes flat, and entirely decorative. Stilettos, tights, shirts, and a chic handbag, are the modern playthings of the middle classes. As Kamuanga appears to proposition a continent affected as much by globalisation as any country in the west. And scrutinises the desire in Africa to look more western. His inspiration for the canvas is based on the aspirations of a new generation, who want for something alien in order to appear more individual at home. Elongated Head (2014) goes even further to suggest that one’s appearance can be hijacked and not enhanced by the ideals of an alternative look. His central figure is camouflaged entirely by loosely fitting headscarf’s that cover her head, and her dark body appears to be decorated in a circuit board aesthetic. That suggests she may be programmed to want something else entirely. While her unruly hair style appears almost alien, in her desire to be individual.

Eduardo Berliner, Woman with Dog, 2009.

Eduardo Berliner, Woman with Dog, 2009.

Brazilian Eduardo Berliner’s lighter canvases read like anecdotes to perverse middle class practices. Heightened moments when reality is subverted by absurd scenarios that might otherwise have gone ignored, or been correctionally bypassed; are for Berliner the focal point. Whereby the routine of a more settled reality appears less interesting, and entirely unengaging. Woman with Dog (2009) is an oil on canvas that has something of the candour of any fool-hearted ‘selfie’. And beneath what is a well-executed work, lies an almost explosive humour that rises to the surface in a deafening volume of heightened jubilation; when animal and owner wrestle for one another’s affection. And for Berliner it is in this uncanny moment when normality is replaced by the imposition of chance; (when the sitter holds her dog aloft and her skirt becomes entirely unsettled; replacing her face with that of her dog), that there is something more rewarding to be had. Handsaw (2009) is another work that holds reality to ransom, in an attempt to examine the folly of letting one’s imagination run riot. Berliner’s lead protagonist in this work appears to calmly stand over a giant tortoise in order to cut it in two. Resembling the mechanics of a magic trick, with the audience congregated on this side of the canvas; the female character appears entirely convinced by her actions. As Berliner appears to profit from his own inventive imagination.

Hamid El Kanbouhi, Dans, 2012.

Hamid El Kanbouhi, Dans, 2012.

Moroccan born, Amsterdam based Hamid El Kanbouhi single canvas, Dans (2012) appears as a crude investigation of international politics. As the two central protagonists appear to wrestle for overall control of the machinery that binds them together. As a figure in a western styled hat stands with his/her hands aloft, opposite an African/Middle Eastern styled man, who also has his arms outstretched. In an action resembling two puppets pulling at one another. In order to maintain the precarious equilibrium between those giving and receiving. And for all its imperfections Kanbouhi appears to have created a visually arresting scene of two figures vying for temporary control.

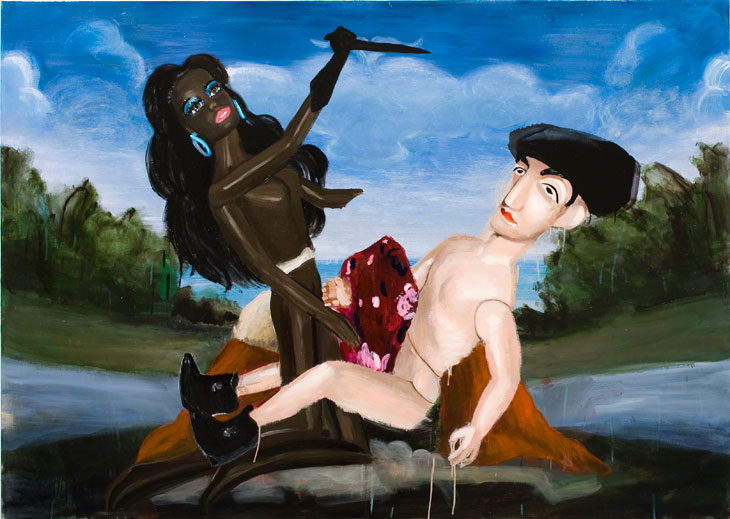

Alida Cervantes, Matadora, 2011.

Alida Cervantes, Matadora, 2011.

Alida Cervantes’ canvases similarly appear absorbed by an inebriating absurdity, as they have a narrative entirely of their own. Likened in part to Italian Giorgio de Chirico’s dreamscapes, Cervantes’ canvases are rooted in the idea that her visual renditions are entirely plausible. Matadora (2011) is an almost comical take on two cavorting dolls, (at the centre of the canvas); that appear to have been captured in a moment of unruly violence. As the black female protagonist clenches a knife in one hand of two arms sprouting from her right shoulder. That appears destined for the action man styled chest of the white male. And just as Jean-Franҫois Boclé uses plastic bags to address grander notions of creed and colour, so Cervantes creates crude renditions of fanciful figures, to proposition where power lies. For those submitting to it, to those wheeling supremacy like a knife. Obviously in Matadora Cervantes subverts any preconceived idea of who has control over whom. And for all its childlike charm, Cervantes’ work appears to challenge the existing metanarrative, as history has had it perceived for generations.

Horizonte En Cáma (2011) is another canvas by Mexican Alida Cervantes, in which the imagery is symbolic of greater cultural catastrophes. Portrayed as an agent of slaughter, Cervantes’ lead character’s doll like demeanour overshadows her calculated act of revenge. In a purposeful attempt at rebalancing history she appears to have attacked a male. Standing beside an instructive symbol ‘E’ that is struck out, and contextualised by a stage like setting, in which a seascape is crudely attached to a hut, which rests against a tapered background of trees. Cervantes’ scene is puzzling picturesque, but for her punctuated symbolism and menacing smile. Rendering a black dog in the left of the painting, a bloodied knife in the protagonist’s hand, and most troubling of all, a penis that appears to have been hacked off of a male in an act of vengeance. The troubling undercurrent to Cervantes’ work conveys that where there is tranquillity lies trauma, as Cervantes wrestles with the social, economic and political ills endemic in her country.

Federico Herrero, Barco, 2008.

Federico Herrero, Barco, 2008.

Costa Rican Federico Herrero’s coloured canvases read like child’s play. In which his loosely biomorphic colours sit, stand, and turn over one another in a busy exchange of shapes and tones of varying sizes. In a canvas littered with as many colours and painterly techniques as you might find in a nursery’s play area, Herrero’s palette appears positively glowing; as the canvas appears entirely busy in its own universe. Which is as amusing as it might appear confusing. Barco (2008) is a work in the manner of Brazilian Beatriz Milhazes, but without the geometry of her overlapping shapes. As his ice cream coloured canvas appears to proposition a world in which colour is at the centre of everything imaginable. Untitled (2008) is another colour field canvas that blinds ones senses with an unreality that is as deliciously attractive to the eye, as it might turn traumatic. Ominously in Herrero’s works there appear to be no exit signs; no plausible way out of this technicoloured dream. As visually the variations of green routed around the honeycomb yellow and flatter greys; create a landscape that is as flat as it is claustrophobic. Yet for all that, it is the intensity and metropolis styled activity of the canvas that makes for an attractive body of works; enough to want to lick them even.

Mikhael Subotzky, Pasvang, Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison, 2004.

Mikhael Subotzky, Pasvang, Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison, 2004.

South African Mikhael Subotzky’s documentary styled photographs are as arresting as they prove incredibly uncomfortable. The composition of Pasvang, Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison (2004) recalls something of the labour of Gustav Caillebotte’s The Floor Planers 1875 As these five imprisoned individuals appear to clean the corridor in unison. To a regulated rhythm that is likely to be endemic of their elemental lives in prison. Cell 33, E2 Section, Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison (2004), a work from the same series, depicting multiple male figures all outstretched, in differing states of undress in an open cell. Where they are as likely to be sleeping side by side on the floor, as they are to be sharing a bunk bed. And Shackles, Pollsmoor, Maximum Security Prison (2004) is a more spontaneous photograph of the jewellery of prison life. As a duty guard appears to have collected together a handful of the shackles that keep these men together. Which in context are not too dissimilar to the fetters that held slaves against their will centuries previously. And possibly more troublesome of all, is Subotzky’s image ‘Fuck Me’, Toekomsrus, Beaufort West (2007) of a small girl with the words ‘Fuck Me’ graffitied onto her forehead. As she presses her arms together behind her back, and looks up into the light; it is as if her fate rests in the hands of a more troublesome future.

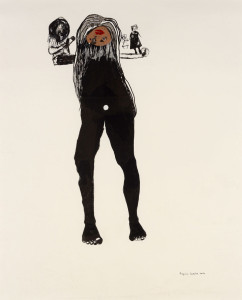

Virginia Chihota, Raising On Your Own (Kurera Wako), 2014.

Virginia Chihota, Raising On Your Own (Kurera Wako), 2014.

Finally Zimbabwean born Tripoli based artist Virginia Chihota’s drawings are testament to a woman who has gone from one totalitarian dictatorship into the hands of another. Succumbing to revolution and civil war, Tripoli is less stable now than when the artist arrived in 2012. Against such upheaval, Raising On Your Own (Kurera Wako) (2014) appears to concentrate on her being entirely alone; and of her having to raise her children on her own. Chihota’s entirely black body is perfectly rendered to the upper torso; where upon it disappears into this macabre and disturbing anti-figure that she scribbles in. With an upturned face, where her head and shoulders should be; and outstretched stubs as arms; Chihota’s figure appears entirely burdened by the responsibility of children. Against a landscape totally tormented by the ravages of war.

Pangaea II draws on works from two vast continents tormented by their own grievances. Sculptural and two-dimensional, that when juxtaposed boil down to the visual exuberance of Latin American, that sugar-coat the causal effects of colonialism, consumerism, and political and social unrest, with unbridled adolescence. And more significantly the constellation of countries in Africa, from where art appears to function as a placebo for the chronic ills of a continent damaged by civil war, starvation, and slavery. All of which makes for a show that is as much about what is behind the curtain, as what is visually present.

Saatchi Gallery London

Pangaea II: New Art from Africa and Latin America

Until September 6, 2015