In Pencil Me Down, drawing again shows itself as capable of holding the textures of life and the complexity and variety of human emotions as any other medium.

Joseph Omoh Ndukwu on group show at Angels and Muse, Ikoyi, Lagos.

Laju Sholola, Portrait 25, 2023

Pencil Me Down Creates a Sublime Space of the Personal and the Pertinent

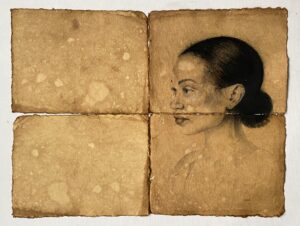

THREE WORKS stand before my eyes as art that pulls the extremities of a room into a small and intimate space of subtle intensities. The first, Laju Sholola’s Portrait 26 (2023): A woman in beautiful cornrows is seen from the back, the silken weaves stopping at her nape in gentle curls. Her face is tilted slightly as in reflection or remembrance, a truly tender portrait. This work, a quadriptych, done with graphite, charcoal and conte on handmade paper, continues Sholola’s committed exploration of space, inwardness, tranquility, and beauty.

Laju Sholala, Portrait 26, 2023

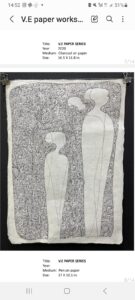

The second, Victor Ehikhamenor’s Father, Son and… (2020): Two white silhouetted figures, one taller than the other, (a father and son) stand against a background darkened by line drawings and symbols. The drawing (pen on paper) is small, scarcely larger than two-thirds of a typical schoolchild’s cardboard paper. The symbols and drawings are tight and done in a fine hand. As in any classic Ehikhamenor, they form their own cavalcade of meanings. Father and son bound by blood and a shared solitude, on a journey to some place even they do not fully know. Famous for his large, swirling works, here Ehikhamenor favours the miniature and contemplative over the large and strident.

Victor Ehikhamenor, Father and Son….2020

The third, Austin Uzor’s Post Industrial Landscape (2021): An empty city made all the more desolate by Uzor’s deft shading and line work (made with graphite on gessoed arches paper) opens out toward us at the same time as it recedes into itself. The lines are straight, thin and hazy, echoing surreal vistas. Abstraction, architecture, and an echo of dreams blend to create an unsettling, melancholy experience.

Austin Uzor, Post Industrial Landscape, 2021

The exhibition in which these works appear, Pencil Me Down, showing at Angels and Muse, Ikoyi, Lagos, features complete sketches and drawings by 7 artists: Akanimoh Umoh, Austin Uzor, Chinedu Ezeifedi, Elizabeth Ekpetorson, Ibe Ananaba, Laju Sholola, and Victor Ehikhamenor. All the works share the intensity of the three works. The ambience as one stands surrounded by them is of an irresistible, albeit quiet, force field. “A mesmerizing visual orchestra” was how Ibe Ananaba, the curator, also an exhibiting artist in the show, described it.

Akanimoh Umoh, AS E Go Be, 2023

Pencil Me Down doesn’t strive to gesture at many things. But what few things it concerns itself with are attended with singular focus. A statement by Akanimoh Umoh, Nigerian figurative painter born in Nsukka, crystallizes this focus. His art, he states, “strives to transmute chaos into tranquility.” In As E Go Be (2023), a young man sits forlorn on a sofa, his arms lifted to frame his face. His frailty is emphasized by the delicateness and liquid precision of Umoh’s lines. He looks like the common man, moving through life as best he can, trying—not always too successfully, it would seem—to leave his problems behind.

Deepening the economic or existential frustrations is the solitariness of the figures, like an accompanying note on the larger motifs. Each figure is alone. Each figure is sublime. The solitariness, oftentimes loneliness, of the figures echo the preoccupations of the artists: solitude, introspection, rage—ultimately the soul-textures of what it means to be alive in Nigeria, to be alive in the world, now.

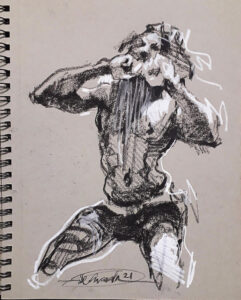

Chinedu Ezeifedi, Echos of the Unseen, 2022

Echoes of the Unseen (2022) by Chinedu Ezeifedi, a Nigerian artist based in Canada, is a charcoal sketch of a man in anguish. It looks unfinished. But to make it, or expect it to be, any more finished than it is would be to miss the point. The man clutches at his head, his body bent forward. He is in pain. He is walking forwards in pain. He is unclothed. Around his core is a turgid blur of darkness. The painting is all these things: confusion, pain, rage, and a relentless scattering.

Ibe Ananaba, Joy Comes in the Morning 4

Emotions of pain and rage, of confusion and despair are often the easiest to trace as they seem the most acutely felt. On the wall adjacent Ezefeidi’s are Ibe Ananaba’s fuzzy and heavy-lined sketches of a deadlocked figure. At first glance, the sketches look like those of a man exerting himself or struggling deep within with something heavy. But with another closer look—and assisted by the title, perhaps—it becomes apparent that the figures are dancing. They are portrayed in a mood of celebration. Still, this is no untroubled celebration; there’s the heaviness there, a counterpoint of struggle. The series (from which 3 are shown) is, quite tellingly, titled Joy Comes in the Morning.

In Beau (2023), Elizabeth Ekpetorson builds faces out of intersecting, angular shades. The sharp lines and planar aspects reveal Ekpetorson’s cubist influence. They, however, are not hemmed in by them. They impose on that influence their own style, fusing it with techniques of realist figuration. Their three works in the show are head portraits, each done with charcoal paper, as though unequivocally penciling down her thematic concerns of identity, individuality, and unhampered self-expression.

In Pencil Me Down, drawing again shows itself as capable of holding the textures of life and the complexity and variety of human emotions as any other medium. Its work, in the hands of the 7 exhibiting artists, has been to accompany all that we feel, both the elusive and the gut-wrenchingly vivid, to their seldom predictable destinations. Its work has been to carve out a space for all that is personal and universal, all that we are, really, when it comes down to it.