Thulile Gamedze reflects on the urgency of creative, transdisciplinary practices for black women in postcolonial spaces, thinking through artist, collaborator in iQhiya collective (1), and friend Sisipho Ngodwana’s work.

Sisipho Ngodwana: On Misbehaving Cultural Capital

‘Exuberantly metacritical hope has always exceeded every immediate circumstance in its incalculably varied everyday enactments of the fugitive art of social life. This art is practiced on and over the edge of politics, beneath its ground, in animative and improvisatory decomposition of its inert body…’ (Harney, Moten, 73:2013)

One thing that ‘decolonization’ seems to tell us, as bodies departing from the capital-colonialist construct of humanity (departing from white + man + male + heterosexual) is that our existence is strategic. It is not an existence of sociality – as people with lives, humor, and families – but rather an existence as a vessel with the ability to birth objects whose value, and therefore ours, is in giving legitimacy to spaces posing as progressive.

Choosing to operate solely ‘of’ the institution therefore means carrying ideas and nourishing them, comforting them, and feeding them using one’s own means, before having them stolen, and displayed as pillaged objects in a curiosity cabinet, in which the next thing you know, you are sitting on a panel discussion. For as much validation and opportunity a black woman may receive in these progressively dressed arenas, this validation is given un-freely, and with the condition that one’s tangible output is an acceptable measure of the total value sum of the person from whom the work emerges.

Sisipho Ngodwana, 2017, Affidavit i: Notes From an Unfinished Dialogue , University of KwaZulu Natal Gallery, Durban, as part of iQhiya exhibition

Of course, feeding ideas, making sense, and producing things is quite a beautiful labor, but it is easy to be caught in a space where one’s value is not as a participant within discourse, but rather as a ‘socially dead’ black body, whose value is not participation but production. We can understand then how many black thinkers have arrived here and hereabouts, as a pervasive feeling of self-negation seems to intensify, rather than quieten with the volume of critical work one puts out. I have included a quote at the beginning from Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s book The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (2013), which seeks to describe the unavoidable fugitive nature ascribed to oppressed people claiming a social life, through participation in spaces which validate us but are not seen as legitimate, of learning that are not seen as educational, as activist, which are framed as criminal, as boycotting, which is seen as unprofessional, and as restorative, which will be framed as unproductive. The social life of the black gendered creative practitioner cannot be found when our primary associate is the institution.

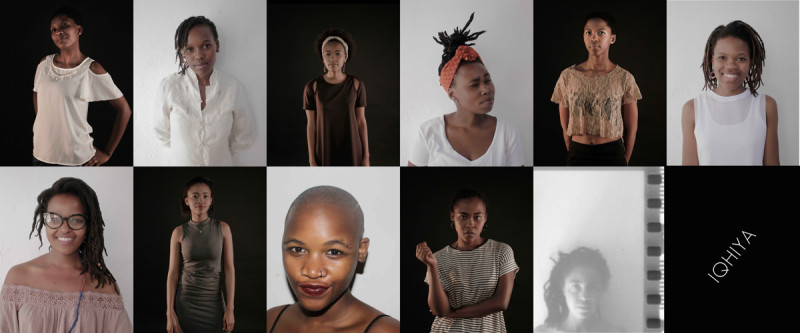

iQhiya Collective. (1)

The evaluator, or the owner of this gaze is of course white liberal-leaning society, whose acceptance of black existence works in stringent terms, continually measuring your body, determining and re-determining the value of their personal or institutional association it, and its potential to add cultural capital to what they represent.

For whatever reason, the arts occupy a position of apparent open-mindedness, openness, and creativity, and thus working within these spaces, in Cape Town at least, means that the norm is dressed up slightly differently than in most fields. When I started writing about art, I learnt quite quickly that full investment into this scene was an unhealthy life choice for a black woman- that the infallible but codependent couple, hope and criticality, would continue their soiree but that my job was not to write them into existence, but was rather to exist, and to nourish the in-between, impossible spaces in which I just did exist.

Sisipho Ngodwana frames herself as an artist. Within this idea lies a radical assertion of what art practice can look like, taking apart the specialized disciplines happening between art production, collection, curation, exhibition, and sale. I say this because if we were to frame her career using an ‘interdisciplinary’ understanding, we might then talk about her as a multiple – a curator, writer, an associate of a successful gallery, a director, an artist, a thinker – but when we take these things as necessary facets of a radical creative project, we come back to the central idea perhaps of a creative practitioner or a cultural worker, or perhaps we just come back to Sisipho.

Evan Ifekoya, 2016, Ebi Flo (We Are Family), still from digital video, 4:26, image courtesy Stevenson Cape Town, as part of The Quiet Violence of Dreams

Ngodwana produced a show in 2016, based on K.Sello Duiker’s 2001 novel The Quiet Violence of Dreams at the Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town. Reading the novel, and attending the opening as well as events, parties and talks around the show betrayed her approach, which is involved always in producing spaces for the interaction of voices and creativities usually kept arbitrarily apart. For me, Sello Duiker’s novel of visceral, chaotic and terrifying navigations of a growing self, Tshepo, within an unpredictable, newly democratic South Africa, itself provided a researched work whose richness was in its refusal to erase, reconcile, or resolve anything about its main character. Instead, Tshepo existed and continues to in the imagined and projected explorations of the reader, the participant, which shows the scope of writing to expand into any arena of production or thinking. The exhibition, based on the novel took this approach forward, simultaneously de-specializing writing and literature, and de-specializing visual art, giving space for both to operate as neither, but both to operate as tools in producing knowledge.

Sisipho Ngodwana, 2017, from Monday (an iChiya performance installation), Documenta 14, Kassel.

Portia Zvavahera , What I see beyond feeling 2, 2016, one of the artists in The Quiet Violence of Dreams (courtesy Stevenson Gallery)

I would argue that this work cannot be separated from newer interventions by Ngodwana, in which writing – as an expansive action – can provide as useful a beginning point, as thinking, making, or interacting can in reading her work. Having been subjected to authorities with rather unimaginative approaches to her ideas on language (she speaks five) during her formal art education in Cape Town, Ngodwana’s relationship to writing and particularly, writing in English has taken on symbolic resonance. As part of a 2017 iQhiya installation/ performance, Monday, Ngodwana spent an eight-hour long school day at a desk, along with the rest of the collective, who intervened in some way with their school desks, writing and rewriting curriculum. This collective piece spurred a trajectory of ideas for the artist, and Ngodwana’s confusing, chaotic, hilarious, politically loaded, and involved web of ideas connected to the desk and ceiling by string seemed to act not just as a challenging artwork, but to embody the challenge initiated in any interaction with Sisipho’s sharp thinking.

Asking questions and putting forth ideas ranging from the nature of love, and the phenomenon of existence, to the natures of hatred, and the phenomenona of global capitalism, and its racialized colonial roots, Ngodwana’s art should not be defined as ‘text-based’, or perhaps even as an art object, but rather can be thought of as an interaction, seeking to breed more interaction. For me this is important because of the fact that the birthing process of the idea, object, or artwork in this case cannot be separated from the fact that the artwork in turn births the artist. Without getting too deep into these reproduction metaphors, I just want to assert that these approaches that turn a production process on its head, and confuse our understandings of a beginning and end, and of an idea and a person, are one way that we can embody radical practices that make it difficult for institutions to objectify us in furthering faux-progressive politics.

The trans discipline describes something different than the interdisciplinary, which is concerned with experimentation with multiple disciplines in order to produce new ways of making. The transdiscipline, although perhaps methodologically similar is not characterized by a desire to make new methodology, but rather acts as the methodology, making improvisational use of multiple disciplines with the aim of producing something that provides a mode of learning about the world. The transdiscipline is occupied with the knowledge it has the potential to produce. It seeks not to make objects, but to create space for ideas.

Ngodwana is a fugitive, an agent of the transdiscipline, working amongst, with, about and in relation to an institutional art culture, which she uses as a vessel for imagining stories and ideas which cannot possibly be contained within it. In a moment where we can spend time confusing the validation given to our work, as validation of the self as a social, emotional being, practitioners like Ngodwana seem to embody and work amongst multiple mediums, ideas, and approaches, using these in collaboration with and in relation to the self – an existing, moving, living, social thing.