The Bedworks are drawings made with colored pencils in a bed, so in an extended position. It was a way for me to reposition my work, putting away the studio work with all that it evokes as an imaginary of the virile artist working in a technical space. In short it is a work that wants to be domestic; it takes place in this space dedicated to women in art history.

Karima Boudou in conversation with the Moroccan artist Soufiane Ababri

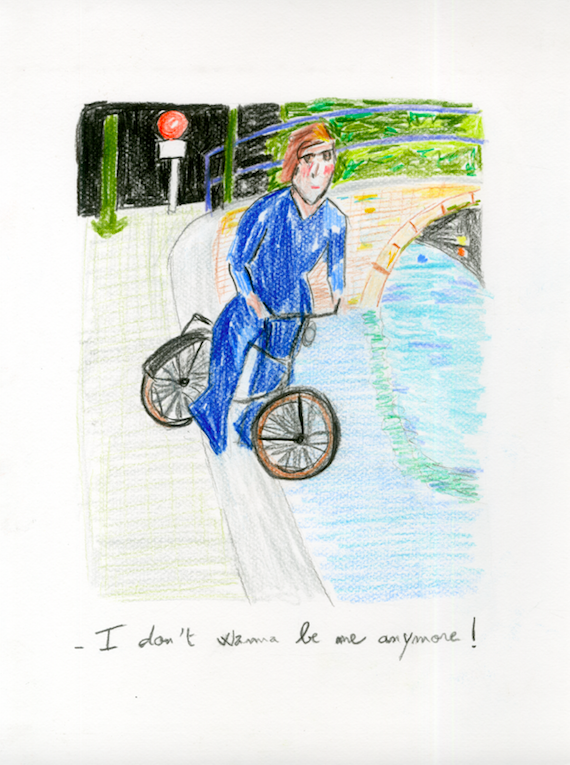

Bedwork, 2016-2018, colored pencils on paper

Bedworks

A Conversation with Soufiane Ababri

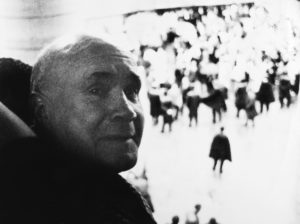

Karima Boudou: The starting point of this conversation is our interest and incessant returns to writer Jean Genet (1910-1986). This common interest revolves around his writings, his persona as well as the near impossibility for the reader or the historian to fully grasp the mythical character that he built and distilled throughout his life. The links and affinities with your drawings that you started in 2016, the Bedworks spontaneously intertwined with the thread of our discussion on “magnifying judgments”, of which the writer speaks. What do they induce in your work and how did they influence the Bedworks?

Soufiane Ababri: With Jean Genet, there is a real desire to rebuild oneself, to control one’s story, to magnify it by making it one’s own and push it out of control. From the perspective of integration or of a will of a social transfuse, these strategies are very common. Wanting to belong to a higher social class than that of which an individual is born, by adopting the attitudes of the bourgeoisie is common. With him, it is the destruction of all codes leading to acceptance or any form of belonging. He made efforts as insistent as his writing to make his life more miserable than it really was. He strove to rebuild from the depths, glorifying theft, treason, cowardice, fear. Vile feelings that are used as insults by the majority were used and advocated by him as our qualifiers.

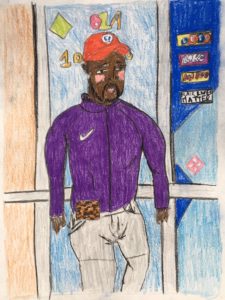

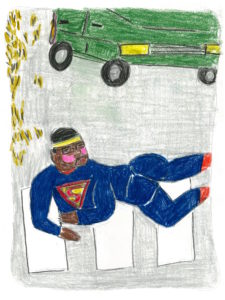

Soufiane Ababri, Bedwork (Genet & The Black Boy), 2016-2018, colored pencils on paper.

The magnificent judgments advocate the right to have a different and differed view of what surrounds me. I want to have the right to keep my eyes marked with stigma in seeing the world and therefore in the way you see me. This ties in with Genet’s idea of the mirror. But with him this idea is present in a radical way because there is no “we”, – the writer turns against everyone. This same idea of the mirror and solitude is found in another powerful writer, Tony Duvert (1945-2008).

KB: When we talked about Genet, I shared with you this image which is an engraving by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1607-1669). In this work, the Dutch artist alludes to the story of Faust who abandons God by making a pact with the devil to exchange his soul for knowledge. The engraving immortalizes a supernatural moment with a magic disk that enters the room and illuminates Faust. One can notice Rembrandt’s attention to the elaborate lines and the perspectives used, pointing us towards the center of the composition where Faust and the luminous disc are represented. This engraving establishes a dialogue between reason and fantasy, a divine and mystical intervention with a sophisticated, even dramatic light. This work of the mid-seventeenth century takes a complex theme and makes it magical. By extrapolation, we could consider Faust, today as the ancestor of a stolen picture from the Seventeenth century in the Netherlands. Is this element of the stolen photo a prerequisite for the development of your Bedworks?

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, Faust, engraving, around 1652, 21 cm x 16,2 cm.

SA: I think that Jean Genet is more Rembrandt than Faust. He has never given up religious imagery and comparisons of holiness, the Carolines’ funeral procession, the character Divine, Our Lady of the Flowers ... but it is a religion of shame that is glorified. He leads me to think of an artist I discovered when I spent some time in Barcelona, to go back to the places where Genet claims to have been. This Spanish artist known as Ocaña (1947-1983) was a painter and performer. A “fag” as Genet would say, who lived his life hanging out at the Ramblas around the port. Ocaña takes up the Genetian religious vocabulary and he could be the main character of one of his novels.

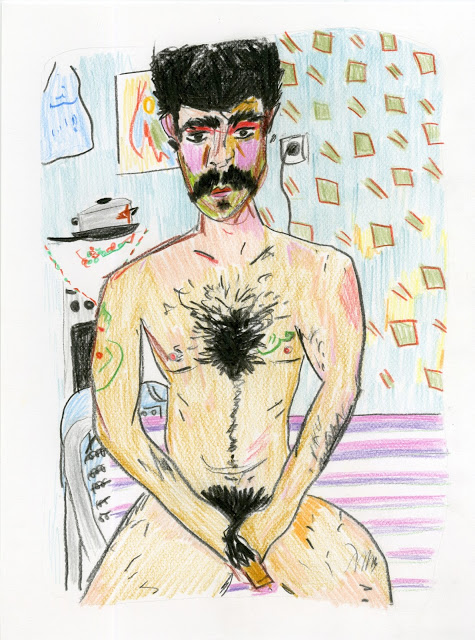

Soufiane Ababri, Bedwork, 2016-2018, colored pencils on paper.

Me, I might be more Faust. I have both feet in the real, and any idea of verticality revels in me. This idea of theft that Genet used because it was inflicted to him, could be quite heard in a certain France where “the Arab” is considered as a thief. The Bedworks often take as a starting point the stolen image taken without consent, in the streets, bars, and other places from people stealthily known. They play with the imitation of other works that I re-read differently or works belonging to my “family” of artists.

It’s almost an amateurish theft or bad theft, as when Edmund White reports that Genet was a bad thief getting caught every time. For my part, there is no desire for heroism or to be tied to the virile image generated by that of the thug.

Photograph by Patrick Ghnassia: Jean Genet at the balcony of Théâtre de France, during the representation of The Screens, May 4, 1966. In the background of the image, several policemen contain, place of the Odeon, protesters hostile to the representation of this controversial theatre play that caused the scandal. Photograph reproduced in Genet by Edmund White, by Chatto & Windus, London, 1993. White is one of the first American writers to speak of him as belonging to the gay world.

KB: Just like Genet, with the Bedworks you put the subject of homosexuality on the table and the element of the mirror of the magnifying judgments plays a role in this narrative thread. Can you tell me more about the ‘operating mode’ of the Bedworks? Beyond these aspects, how do you create affinities between your drawings and artistic, literary and political figures who in their life and history have integrated and articulated their position as homosexuals, in their work and in society?

SA: The Bedworks are drawings made with colored pencils in a bed, so in an extended position. It was a way for me to reposition my work, putting away the studio work with all that it evokes as an imaginary of the virile artist working in a technical space. In short it is a work that wants to be domestic; it takes place in this space dedicated to women in art history. We observe this in Flemish or Orientalist painting in particular. This elongated position is also a figure in the history of painting. Women, slaves and Arabs are often depicted this way in Orientalist painting. It is a strategy of the bourgeois heterosexual white man to master the subject, making it passive, offered, lascivious and controllable. I take this same position to talk about subjects that concern me and that allow me to rewrite myself.

In this logic of rewriting oneself, I establish a dialogue with certain artists. I see it as a family of references that allow me to propose scenographies for my drawings and as a source of inspiration in their realization. I try to introduce ways to disrupt history, by taking into account that certain periods and events can allow to reassess the world in a different and deferred way. That’s how I started thinking about my dialogues with Félix González-Torres (1957-1996), Guillaume Dustan (1965-2005), Derek Jarman (1942-1994) and of course Jean Genet, as well as others …

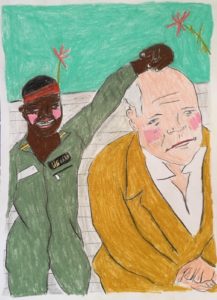

KB: To continue on the subversion of the artist’s willingness to disrupt a work environment and art history, how far do you play with the terms “posture” and “point of view” in relation to the history of the artistic movements, forms and ideas that we inherited? In some of your drawings, you invoke artists who are today “recognized” in art history, such as William Pope L., Félix González-Torres or David Hammons. What happens when you incorporate these figures into your drawings? What kind of situations do you draw and why do you portray Pope L. and Hammons as anti-heroes, the face that blushes with an expression of doubt and uncertainty?

Soufiane Ababri, Bedwork (D. Hammons Blushing), 2016-2018, colored pencils on paper.

SA: There is a real posture in my work. With the title of the drawings, the techniques and tools used, there is a reference to something other than what is represented in the drawing itself. It is about performative drawing that uses the clichés, the body and the sexuality like political tools. These are questions that really arose in May 1968. There is no determination of authority in what I do, I try to problematize what surrounds me and understand the mechanisms of domination to better dismantle them. I try to understand this by reviewing art history and trying to see what is marginalized and how to take that figure out of the margin.

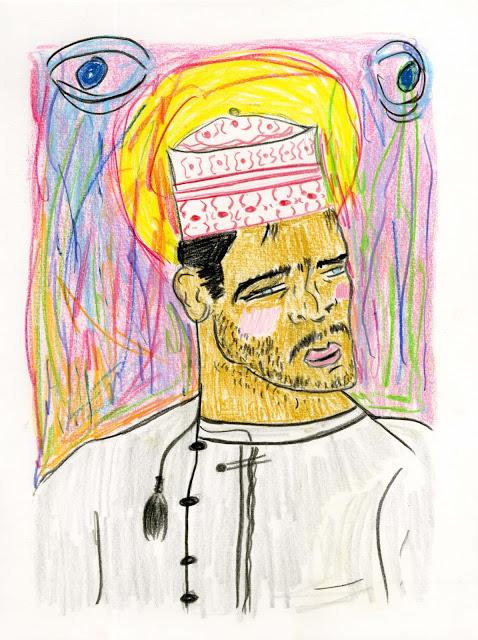

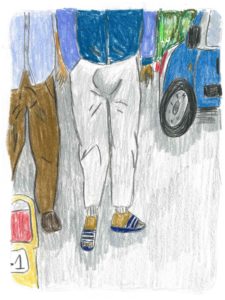

Soufiane Ababri, Bedwork, 2016-2018, colored pencils on paper.

That’s why I think about the modes of copy or imitation. I made drawings where I freely copy paintings of Caravaggio, photographs of Wolfgang Tillmans, performances of William Pope.L or Bas Jan Ader. All these people interest me because they are also in an attitude. I think that the attitude comes from the moment when one is convinced of the relevance of what one brings to the world, and that what we read acts on our future life. From this perspective, books are very important to me.

Soufiane Ababri, Bedwork (William Pope.L Strike a pose), 2016-2018, colored pencils on paper.

KB: You recently sent me a video that functions like “stolen” images filmed in a hurry. The crime scene takes place in Ménilmontant in Paris and could be based on a Genetian novel. We see in the video a group of Algerian Chibanis, former immigrant workers from the Maghreb and with a certain age. They are all gathered around a table and one of them holds in his hand a small Berber flag. The debate seems heated. One of them wearing a cap seems to be agitated and he annoys everyone with his scathing and insistent comments. Seeing these images I told myself that this man is a pure and hard Berber identitaire. They are certainly former immigrant workers who live in Paris in what we call in France “foyers”, nostalgic and bitter of the reality left behind in their home country. Your Bedworks also take as a point of departure situations and moments similar to the one I just described?

Soufiane Ababri, Bedwork, 2016-2018, colored pencils on paper.

SA: Yes, it is in these neighborhoods that I steal the most photographs. Of course, there is homosexuality in my work which is treated as a relation to the world. There is also immigration, racialized relations, the relation to visibility, to colonial history, to the impossibility in our countries to accept the difference. The Bedworks are moments. I draw my point of view, which is not shared by the majority. One just needs to talk about free sex so that people facing you build a negative image on your person, very close to insult. This man was insulted by the rest of the group since he was radical, his position in relation to the Berber identity led him to reconsider his relationship to others, to religion, to Arab domination … Me too, and I think that I created my posture against the insult. Didier Eribon, in the beginning of Une morale du minoritaire: Variations sur un thème de Jean Genet asks the question: “How do they succeed in transforming this filiation heavy to carry and who should dedicate them to fear, concealment, the nightlife, into a source of energy that produces its own light?”

Soufiane Ababri, Bedwork, 2016-2018, colored pencils on paper.

KB: In Principes d’une pensée critique, Didier Eribon speaks of “haunted lives”, it is a reference of which you spoke to me recently. How does he evoke this in relation to gay life? What is the link with death and public space as a space for expressing the history and future of these communities? These questions make me think of the news with the recent massacre and shooting in the club in Orlando, Florida.

SA: Haunted Lives is the title of my solo exhibition that opens on May 5 at Praz-Delavallade. I am also working on a traveling exhibition proposal with actors that will start in Toulouse during the Marathon des mots in collaboration with writer Abdellah Taïa, and then in Geneva with the Collectif détente. This proposal articulates my legacy of AIDS years in literature and the visual arts. Its title is Humez l’odeur des fleurs pendant qu’il en est encore temps. This title is borrowed from a novel by David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, a sentence he repeats eleven times at the end of the last eleven paragraphs of the book. David spoke to me at the end of his novel, to “me” who is also an “us”.

That’s what this is about, the way we inherit things that we have not known personally and that touch us strongly. AIDS, the Stonewall riots, the story of the cups (or tea room), public gardens. The best example, which works as a metaphor are the gardens of the Louvre Museum. This high place of the glory of the French power which is now exported as an imperialist value in the Arab countries, houses after the sunset men who turn in circles to flirt and have sex in the public space. It’s like the negative of the museum used by this community that comes out at night and until dawn, for anonymous and furtive meetings. This is one of the oldest flirting spaces in Paris. How can we decipher it and practice it with all the codes of honor related to anonymity, secrecy and risks? These gardens are also related to the history of assaults and police raids that took place there, which are things that are inherited.

Soufiane Ababri, Bedwork, 2016-2018, colored pencils on paper.

KB: Who is your audience in relation to the Bedworks? What is the link with Torres’s work in relation to this notion of ‘public’ and the fact that his studio was under his bed? He had a bed with drawers in its lower part and for the artist everything had to fit in this space. Even if your work seems to be far from the concerns of relational aesthetics (with all the possibilities and limitations that the latter brings with the problem of identification, social control and private property), why do you invoke Torres between the lines via several levels in your work? You do it at the level of the execution of the Bedworks but you also include him in what you call your “family of artists”.

SA: I remember reading this information about his studio being under his bed in a discussion with Ross Bleckner. Besides that, this discussion interested me a lot because Torres is confident and explains his work with an emotion and intimacy that generates a discussion between friends. He talks about his collection of Disney figurines and their role as antidepressants. I started collecting and photographing them in my hand since the beginning of my panic attacks in Barcelona. He talks about his lover Ross and their encounter. I would even go so far as to say that it is his private life that interests me and the way in which his biography and intimacy are key to reading his work. And then of course there is “Untitled” (billboard of an empty bed), a beautiful work that is a reference for me, and once I mention this it may change the way you perceive my work. The bed is of course linked to intimacy, eroticism and pleasure, but it is also about loneliness, pain and death. It’s like the sublime photograph of AA Bronson entitled Felix Partz, June 5, 1994. He photographs Felix Partz, a General Idea member right after his death because of AIDS. The textiles and fabrics around him on the bed are extremely colorful and vibrant and it took many years for AA Bronson to know what to do with this photograph.

The family of artists is for me a way to take over history, by choosing points of reference while not undergoing the whole part. So I would go for Félix González-Torres rather than Carl Andre, for Tom Burr rather than Robert Smithson. I like to research in their intimacy, imagining them as desirable, close and intimate.

Félix González-Torres, Untitled (Fear), 1991, HM Prison Reading.

KB: Since the private and public spheres are so connected, do you think there is a need for your work to separate them or to define these two terms? Increasingly in our time and even historically, our fantasies, intimate desires and dreams are often dominated by the public sphere. In which directions do the Bedworks lead us in this perspective, they do not suggest any imposed or defined direction? I like to think of them more in a situationist vein than in the very clearly limited palette and scope of relational aesthetics.

SA: I show a relationship to visibility but it is also a question of thinking the tools of control set up by society. These tools aim at keeping control with the institution of the traditional family, of moral that I contextualize in order to disrupt them. But I decide to stop when it becomes an interrogation report and when you have to reveal everything. I do not have a model to impose and I think it takes a variety of relationships to things so as not to erase the specifics of each of them.

The Bedworks are my way of problematizing what surrounds me. It happens in the private and in the public spheres, from that intersectional position in which I am. This position also makes me feel at home nowhere except in this position of the elongated drawing which becomes a geographical and historical link.

Bio artist: Soufiane Ababri was born in 1985, in Rabat, Morocco. He lives and works between Paris and Tangier. Soufiane Ababri is known for his “bed works”, works on paper made lying in a bed. In essence, he examines the ambivalence of a society that is crisscrossed by tensions that are not so much the reflection of its contradictions, but rather of its complementarity. His heritage lies in his own story, built up by layer upon layer of personal and intimate events. A lover of sociology, Ababri’s entire body of work plays with the idea of seeing: the artist observes a world that observes him in a form of introspection combining his own unique perception, shared representations and accepted social facts in an exercise that is reminiscent of Persian miniatures and their subtle play with what is hidden and what is revealed.

Soufiane Ababri holds a BA from Ecole Superieure des Beaux-Arts de Montpellier, an MA from Ecole Nationale Superieure des Arts Decoratifs (Paris) and a post-diploma at Ecole des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. His work has recently been exhibited in London, Paris, Mexico, Montpellier, Lyon, Montrouge, Vitry, Bourges, Tours and Rabat.