To this end, the one thing all 150 pieces in the exhibition have in common is the unwavering belief that somehow their existence would bring black people out of the cultural, political and social quagmire they were trapped in, and in doing so move them closer to the promise of equality.

Christabel Johanson visited the Soul of a Nation exhibition in Tate Modern in London.

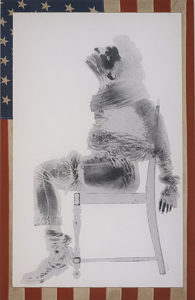

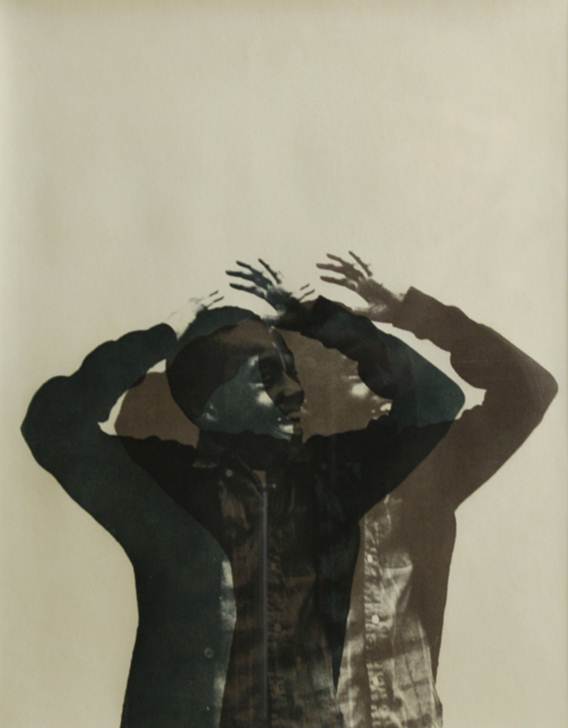

David Hammons, Injustice Case, 1970.

Soul of a Nation

Art in the Age of Black Power

A review

In a climate that is so politically charged, the Tate Modern releases its Soul of a Nation exhibition, marking two decades of black activism and art. “Art in the Age of Black Power” is its strap line; evocative words in 2017 amidst race riots and controversy. The term “black power” carries the weight and connotation of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and the Black Panther movement. More challenging was if the Tate could offer up a nuanced portrayal of the struggle, balanced in its documentation of the years that followed Martin Luther King’s march on Washington.

Romare Bearden, Pittsburgh Memory, 1964.

Spanning 1963 to 1983 the different factions, agendas and radical groups that sprung up as a reaction to the Civil Rights movement are presented in this ambitious exhibition. Beginning with the Spiral art group and Romare Bearden’s collages, we move onto the Black Panther magazine covers designed by Emory Douglas. Black Panther co-founder Huey Newton stares fearlessly from one cover, holding rifle in his hand and a spear in another. He sits on his throne-like rattan chair over a zebra rug, evoking the power of an African warrior-king. The message from the Black Panthers has been clear in its unapologetic approach to gaining black power. These are the first rooms of twelve which make up Soul of a Nation, and at this point the concern lies with the presentation of aggressive, angry black art fuelling the idea of the “black threat” when tensions in America and the UK are high. Do these pieces educate or merely add to the propagandist view of black people?

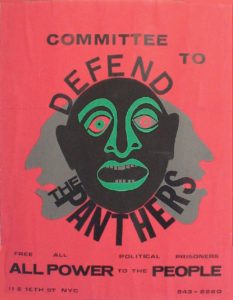

Accenting this is Faith Ringold’s “All Power to the People” poster featuring what seem like a family armed to their teeth; two adults, maybe parents with shot guns and a little boy holding a metal bar. “Free all political prisoners” it exclaims with the lingering threat of black violence, generational and ferocious brimming against the blood-red backdrop.

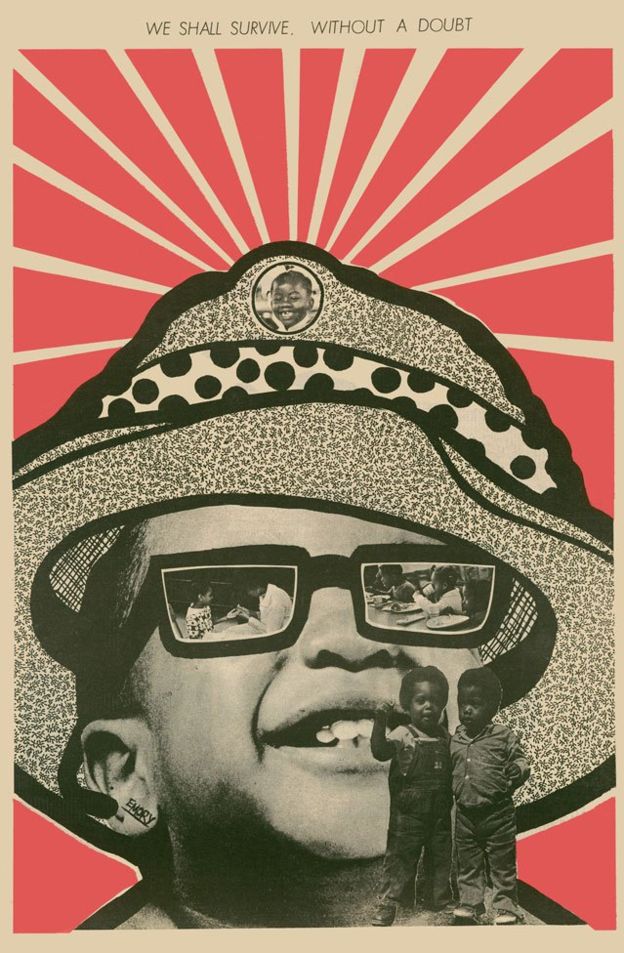

Emory Douglas.

Black aggression is of course an unavoidable discourse. Emory Douglas appears again in “Revolutionary Student”, a piece which conflates education – specifically black studies – and a call to arms. So far violence is presented as a close companion to the activism of the time. This unforgettably characterised the era but with yet another visitation into its gory past, we run the risk of vilifying and misunderstanding the civil rights mission altogether. What about portraying art itself as the weapon of activism?

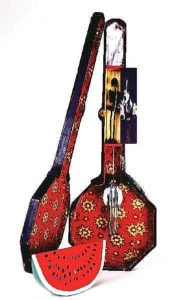

Betye Saar, Sambo’s Banjo, 1971-1972 (Courtesy Roberts/Tilton, New york)

We are thankfully offered more insights moving through the other rooms. The artwork elsewhere reflects a shake-up of society’s institutional racism. “Sambo’s Banjo” by Betye Saar is a teeth-gritting reminder of the “norms” once held by many. Inside the case a wooden watermelon and a lynched skeleton remind us of the stereotypes once held as truth and the fine line treaded by black people. Later we come across a framed “mammy” sculpture, inside her from hinged apron doors a portrait of a black nanny and white baby stand in the background of an erupting black fist; reclaiming the space of black oppression.

Poster Faith Ringgold.

“Injustice Case” by David Hammons depicts activist Bobby Seale bound and gagged, echoing his abuse in a Chicago courtroom, where Seale was part of the Chicago 8 trialled for conspiracy following a violent protest. The piece is framed in the Star-Spangled Banner conflating the American justice system and its historic and explicit repression of the black voice. Pieces like this and “Fred Hampton’s Door 2” by Dana Chandler exemplify police brutality and injustice powerfully. The bullet-riddled door stands and repeats the green and blood red colour scheme of Ringold’s “All Power to the People”.

Further on, pop-art favourite Andy Warhol’s own screen print of Mohammed Ali is displayed. Originally part of his Athletes series, Warhol uses a powerful red background much in keeping with the other artists’ colour scheme but this piece seems out of place. Perhaps it is Warhol’s own reputation which weakens credibility as a piece of “black art”, maybe it is the knowledge that it belonged to another body of work but the portrait feels like a superfluous offering to the exhibition.

This raises other questions from the exhibition; is there a true black aesthetic? Does it matter if the artists are black or not? Should the work come first before the practitioner? Through spanning two decades Soul of a Nation captures the work of 60 artists, most of whom will be relatively unknown. Whilst the majority of them will be black, not all of them are. “Harlem: Black Angels” is photo book shot by Japanese artist Ruiko Yoshida, who was living in the neighbourhood in the mid-1970s. She says, “My camera was the weapon with which I joined the struggle of blacks, yellows and other minorities in America fighting prejudice in order to gain their identity as independent human beings.” Capturing the human side of Harlem, Yoshida’s contribution is a powerful reminder of non-violent progress for civil rights, contrasting more commercial pieces like Warhol’s print of Mohammed Ali.

Cleveland Bellow (American, 1946-2009). Untitled (Young Man), 1968. Screenprint on paper, 19 1/2 x 15 1/4 in. (49.5 x 38.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of R.M. Atwater, Anna Wolfrom Dove, Alice Fiebiger, Joseph Fiebiger, Belle Campbell Harriss, and Emma L. Hyde, by exchange; Designated Purchase Fund, Mary Smith Dorward Fund, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, and Carll H. de Silver Fund, 2012.80.6

The human side of the era is revisited in Cleveland Bellow’s dualistic silkscreen print of a young boy. One reading of it sees the child smiling, his hands lifted carefree above his head. Another interpretation sees the boy threatened and grimacing with his hands poised in surrender. Bellow’s ambivalent portrayal invites the viewer to understand how a moment in time could quickly change from safety to danger, life or death, a fine line for most black people and one of the core motivations for civil rights.

*

Another room is dedicated to the AfriCOBRA collective who massed produced posters and wanted to create positive visual images of black people. Uplifting images of prominent leaders like Malcolm X or just ordinary people, positioned the AfriCOBRA group as visually and ethically different from artists like Emory. Wadsworth Jarrell’s painting of Malcolm X “Black Prince” was made for the group’s second exhibition in Harlem and features phrases from the leader’s speech in its composition. Vibrant and colourful, this is an example of how conscious the “soul” of the movement transformed from the dark and heavy artwork to a more varied palette. More psychedelic than moody this is closer to the aesthetic expected of the 1960s and also the funky “cool black aesthetic” which began appearing.

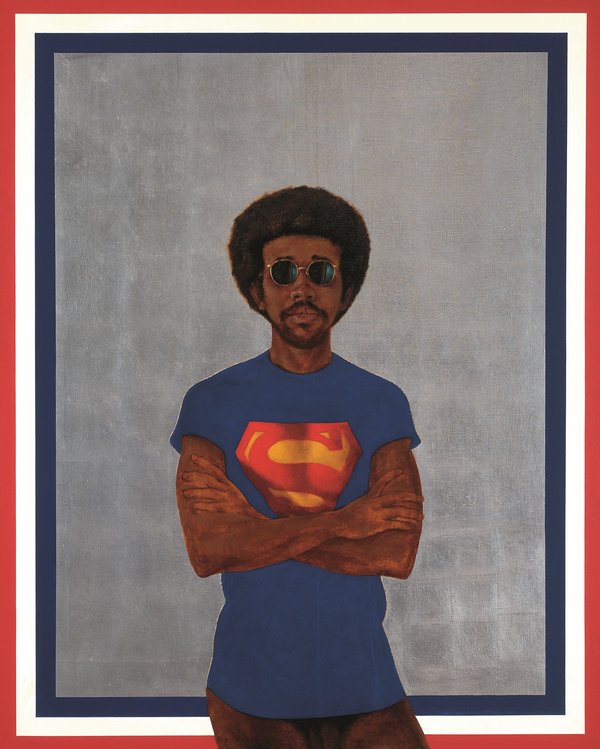

Barkley L. Hendricks, Icon for My Man Superman (Superman never saved any black people—Bobby Seale), 1969.

To this end Barkley L Hendricks’ “Icon for my man Superman” personifies an effortless cool that is mellow and chic but arresting enough to land itself as chief poster for the Tate’s marketing of the exhibition. As a self-portrait, Barkley stands with afro and shades in a Superman t-shirt. This is a response to Bobby Seale’s quote that “Superman never saved any black people.” Barkley doesn’t need Superman, he is his own hero. Framed by the red, white and blue colours he offers a new take on the “All-American Hero” tradition. Barkley further subverts the portrait when as our eyes trail lower, out and below the framing we see a hint of exposed genitals. By working with the imagery of the well-endowed black man he acknowledges the sexual intrigue and threat it poses to the white status quo.

Installation view, 2017,

Threatening the status quo is a prominent visual in Faith Ringold’s, “Die” which shows a frantic massacre scene with blood splattered amidst frightened black and white people. Initially the viewer will see white people as the victims but on closer inspection it is difficult to tell who the victims and perpetrators are. One would guess this is an intentional message telling its viewers that there are no clear villains or enemies. Off-centre sit two children; a black girl and a white boy, huddle together frightened by the chaos around them. We can’t help but draw our own conclusions; is messy politics ruining our future? Are we all just as frightened as the other? Should we work together rather than fight the other?

In this age of black politics and radical thinking, we often hit tragic notes whilst the media directs us towards headline-making events often leading to a polarised view of black power. On the one hand it is pious and peaceful; on the other it is violent and anti-white. So enduring are the images of extremism that we forget the soft and creative expressions of protest, and sometimes we don’t even know they exist.

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #20: Die, 1967. COURTESY THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

What Soul of a Nation attempts to do is present a greater variety of these protests through art and ask if society should process and see it as one black aesthetic. Although the answer is debatable, it is important to remember that whilst searching for opportunity in a time of crisis, “power” for black people meant “equality”. In the struggle for equality, amidst the politics there is a very human journey for identity within the black experience – a search for an identity not subjugated in racism and born from slavery. Thus if there is indeed a unified black aesthetic, I believe it would be determined through its intention. To this end, the one thing all 150 pieces in the exhibition have in common is the unwavering belief that somehow their existence would bring black people out of the cultural, political and social quagmire they were trapped in, and in doing so move them closer to the promise of equality.