I think performative actions carry immediacy, and I think performative actions carry immediate connectivity just the way music does, but I think all art forms do this, can do this, it depends on how you utilise this.

Candice Allison in conversation with Nairobian artist Syowia Kyambi

Fracture (i), Performance, Wiels Centre for Contemporary Art, Brussels 2015. Photo Credit: Joke Floreal.

I ask a lot of my audience emotionally and sometimes that’s hard

In conversation with Syowia Kyambi

Syowia Kyambi was born in Nairobi in 1979, where she currently lives and works. She is a multimedia artist, working primarily in the form of installation and performance with the use of video and performance stills as outputs to share with the public. She explores personal relationships and cultural identities, employing repetition of materials in her practise, or elements of cycles of breaking down and rebuilding – and elements of repair, to examine how our contemporary human experience is influenced by constructed histories, past and present violence, colonialism and family.

Between Us, Performance, GoDown Art Centre, Nairobi 2014. Photo Credit: James Muriuki.

Syowia Kyambi was included in the touring exhibitions Body Talk: Feminism, Sexuality and the Body in the Work of Six African Women Artists curated by Koyo Kouoh, which took place at WIELS in Brussels, Belgium (2015), among other locations; and Kabbo Ka Muwala [The Girl’s Basket] – Migration and Mobility in Contemporary Art in Southern and East Africa (2016), presented at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Makerere Art Gallery and Städtische Galerie Bremen. Most recently she presented work at the Serpentine Galleries Miracle Marathon (2016). Kyambi graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago and has been the recipient of several prestigious awards and grants, including the Art in Global Health Grant funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Between Us, Performance, GoDown Art Centre, Nairobi 2014. Photo Credit: James Muriuki.

I met Syowia in February 2016, sitting on the stone steps of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, which seem to almost have been worn soft by the bums of the many artists who have whiled away the time there; smoking cigarettes and talking deeply about art and life in the welcome afternoon shade.

She had just arrived in Harare to install her work for a group exhibition, Kabbo Ka Muwala. First appearances: sharp hairstyle, mismatched shoes. Ok the same shoes, but one black and one white, with red stripes. Her work had been detained in customs; talks of release were not looking positive. This girl was not a pushover.

Shrugging her shoulders, these things happen. Nothing for her to do but sit and wear the stone in some more, maybe have a deep conversation about art and life. Or jokingly plot all the alternative possibilities for herself and Zambian artist Victor Mutelekeshe; also sitting there wearing in the stone, his work had been ‘lost in transit’.

This interview took place in October 2016 via email and audio file exchanges.

CA: I was first introduced to your work at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in February 2016, where I saw your video ‘Women, Fräulein, Damsel & Me’ (2007 – ongoing). I found the work to be deeply personal, peaceful and poetic on one hand, but there was also an underlying sense of violence and trauma. In your artist statement you say that the work is about exploring your mental entrapment by Kenya’s colonial past in relationship with your father and siblings, with the intention of liberating your siblings and yourself from this entrapment. Was creating this work a form of catharsis for you?

SK: It was actually fabricated in 2007 – 2009, and it was re-fabricated for an edition in 2013. Yes, this work was definitely a process in that. It did create a distance and a release from a certain moment in my past for me which is actually why the performative elements of the work that I did in 2007, and the second performative act in 2009, were done in private settings, it wasn’t in front of a public audience. Yeah, in a nutshell, it did release me and works created after that moment, have a little bit of a different twist in terms of the direct connection to my personal autobiography.

Fracture (i), Performance, Wiels Centre for Contemporary Art, Brussels 2015. Photo Credit: -Joke Floreal.

CA: In the installation and physical performance entitled ‘Fracture (i)’ (2011), your main character, Rose is a woman who is tormented by doubt. She no longer knows where she belongs and is unable to cope with herself either within the context of the rural Kenyan tradition or urban modernity. How does Rose resolve this conflict?

SK: Rose is one character out of two actually that’s in ‘Fracture (i)’ and ‘Fracture (i)’ delves with lost past and present time and the first character is more of an entity that is much more connected to colonial past and history. Rose doesn’t really resolve the conflict. I think what happens to Rose is, at the end of the performative act of ‘Fracture (i)’, she goes into a process of acknowledging. I guess she breaks down, and then she has a moment where she acknowledges her past. And she has a moment in the work where she starts to build, or repair, or put together in a way, these vessels that represent a number of different things, but mostly an identity and a culture of people who are broken down. I think through that acknowledgement comes a moment of repair, and that repair isn’t finished, it’s not done, but it’s initiated.

Rose ended up also moving into a new body of work in 2015 titled Rose’s Relocation and there she kind of moved from the storyline around her move, from moving within Kenya in ‘Fracture (I)’ from a rural space to an urban space in this work, she moves from an urban space in Nairobi to a small town in France. There the output is a series of digital photographs that uses again the memories of her mother’s home that are represented in ‘Fracture (i)’, and herself, walking through the cityscape in Metz, in France. There she also struggles with loneliness. She has the same struggles with the expectations of now living overseas and people back home thinking you a lot of money, the pressures that come from home. So a similar emotional turmoil goes on with Rose even though her narrative has shifted. I guess in the output of that work there’s no final resolve, it’s an ongoing process.

CA: As an artist who not only has dual heritage but also navigates the terrain of extensive travel as an integral part of disseminating your work, how do you negotiate notions of home, nationality and identity?

SK: I have a home (laughs). I definitely created a base for myself which is my home, in order to be able to navigate travelling a lot. It was important for me to have a base which I created on the outskirts of Nairobi, which is also the location of my studio. I think that is one component that was an important process to me, to actually establish a base because yes, I have dual nationalities and I do travel a lot for my work.

One of the things I want to share about travelling is that often I find the time between spaces a really interesting place to think and to generate, not necessarily new ideas, but kind of to, just to have a moment to think and reflect and refrain. That happens a lot for me when I’m in between places, when I’m travelling, and so I find that really important and it kind of is a fuel. It fuels, and a lot of old concepts reappear, the ones that are important for me to do. And I am reminded, oh yeah, I thought about that a while ago and I don’t know why I didn’t focus on it, and I kind of refocus.

Sometimes I struggle with the idea that, as an artist in my practise, I have to accommodate a lot of travel and I think it’s part of the job description of an international artist (laughs). I think that I’m just in a process of accepting that, or coming to terms with that, or realising how much of a component that is going to be in my life and it how it’s not going to actually change very much, and that’s something to think about.

CA: How do local audiences engage with your work? Do you receive different responses in different locations?

SK: Yes and no. One response that’s kind of constant is often people are very moved when they witness a performance that’s connected to an installation. So ‘Fracture (i)’ moved, in 2011 it was in Finland, but also in 2015 it moved to three different locations: Wiels in Brussels, Lund Konsthall in Sweden, and 49 nord 6 est Frac Lorraine in France. Then in 2016 it was in the EVA International Biennial in Ireland. And there’s one thread of response that’s been the same for ‘Fracture (i)’, which is a lot of people stay all the way through the performance, even though that’s not, I mean I don’t ask you for that, it’s not the purpose of the work, but people do that. And people are very moved, and are very emotional. They often come to me afterwards when I’m me, the artist. People want to give me hugs and want to give back. That’s quite moving and it’s quite overwhelming. I think that happens quite often. I ask a lot of my audience emotionally and sometimes that’s hard. Then different people relate differently, so that it was interesting for me to have older Finnish women connect with the knitting imagery that’s in ‘Fracture (i)’, that’s from rural Kenya, kind of like unexpected cross-overs. Sometimes I think people are a little overwhelmed or resist the engagement when it’s too much and that’s also totally ok.

Roses Relocation 1, Metz Series, 2015.

CA: You have been preparing for a sound work/performance entitled ‘Between Loving & Me’, made especially for the Serpentine Galleries Miracle Marathon which took place 8th and 9th October 2016. I saw that you put out an invitation to the public for stories about relationships that have created or affected change in a community or family. What kind of stories did you receive and how did you incorporate these into your performance?

The poster picture Serpentine Gallery used to present the project on their website.

SK: It wasn’t a performance, it’s ongoing work. It probably will end up either as a sound piece on its own, or an installation with sound. But it’s still a work in progress and I’m still collecting stories. This will come potentially toward the end of next year into a more visible format or final product. I got some very special stories about different kinds of love, and how relationships were affected through love. The kind of expectations and disappointments, but also appreciation and something like, I guess, not really a torch, but this idea of carrying something forward in one’s life. Very different kinds of stories. One was about a friendship in the 90’s for example. She had a very special relationship with a person who was shunned by his society for being homosexual and also very sadly he died of AIDS. It was a very special bond that they had and ultimately he made a very special gift to her. Someone else had a house in Spain to act as a refuge for others. A different kind of story that came in was someone whose daughter had heart failure, a heart defect or a heart murmur, and had to have open-heart surgery. And his family didn’t come at the time when he needed them the most and he talks about this at great length. There’s a difference between his relationship with his father as a result, and his relationship with his sister, who actually he wasn’t very close to but she made the effort and came to the hospital and his father never did. I think there was a big change in their relationship and their dynamics, and a big change in himself and how he views his family, the world and the space around him, the people who are family, and what is family. Those are just some examples. It’s an ongoing work so if people still want to submit stories they are more than welcome to do so. I’m going to do another explanation and call-out through my newsletter and my website, it’s just taking me some time to settle down (laughs).

CA: Did you use everything that was sent to you, or did you sort through and select from the material you received?

SK: Yeah, at the moment I used everything that was sent, because it was not so much material, but I did edit, kind of shortened the clips, to make them quicker, cleaner, for three minutes, but without undoing the story, more like the ‘uh-uhmms’, you know, that can be edited out. Yeah, so the storyline isn’t altered or what people say isn’t altered or juggled about, it’s just taking out the breaks in between when you know people are processing or clearing their throat.

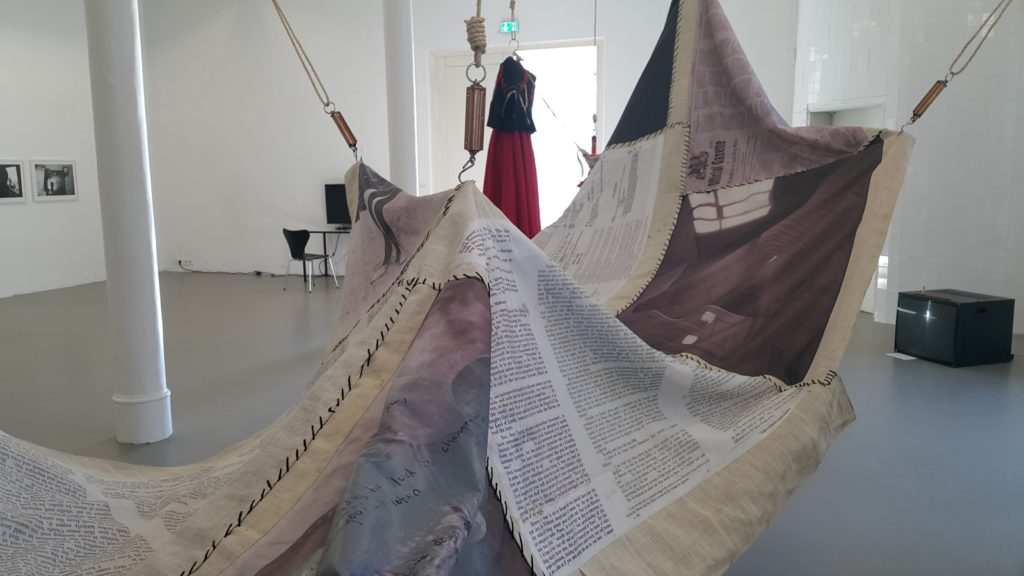

I Have Heard Many Things About You, Performance, Bremen 2016.

CA: Speaking of marathons, I want to talk about your performance ‘I Have Heard Many Things About You’ (2016), commissioned for the third leg of the touring exhibition Kabbo Ka Muwala [The Girl’s Basket]. You walked through the streets of Bremen for four and a half hours, wearing a traditional Herero commemoration day dress and dragging a 14 meter veil which showed archival text and images. I can imagine that this was not only physically but emotionally taxing. What you were instigating with this work?

SK: The initial connecting point was actually with the Übersee-Museum, and the curator Ingmar Lähnemann from the Städtische Galerie Bremen, was also looking for connections, connecting Bremen to the topic of the exhibition. He had come across a permanent installation I had done in the National Museum in Nairobi which used archival material. He actually asked if I would be interested in thinking about working with the material in the Übersee-Museum which houses a lot of artefacts that were collected during colonial times, as it’s an ethnographic space. I was interested in that, but I actually didn’t end up working very heavily with the direct materials in the Übersee-Museum. I ended focussing a lot on the way stories are told. They are told in many layers of narration down the line, so the material that I used in the work and in the research is second hand archival material. So for example, I spent time at the Mohamed Amin Foundation. Mohamed Amin himself took several photographs in Namibia in the 90’s and late 80’s for a tourism book, and through that he obviously took pictures of commemorative monuments in Namibia. I was looking at these monuments from a photograph, from a time that was very different from the time of my actual research time period, which was more focussed on Germany’s colonial history in Namibia.

Bremen is an interesting city because a Adolf Lüderitz who was born in Bremen was the founder of Imperial Germany’s first colony. Lüderitz town, a the port town, one of the main export locations of raw materials out of Namibia was named after him. And so with this history they do have a discussion to have as a society in Bremen and in their history in Bremen. It was at one point a very wealthy city and at the moment it’s actually not. Its tax money goes to its neighbour Saxony and it doesn’t trickle back into the city, so the city itself at the moment is a little impoverished in terms of what it used to be historically. I was interested in initiating more moments of dialogue, or creating platforms that would initiate conversation about this colonial past. The title ‘I’ve heard Many Things About You’ is derived from a letter that was sent by Namaqua chief Hendrik Witbooi, who was a main chief in Namibia. He was one of the strongest leaders against colonial rule in his country, and he kept meticulous records of his meetings. He wrote a lot of letters: to the British, the Germans, to his counterparts, the chiefs he was at war with. And these letters, and he himself as a personal character, became a strong focal point for me in this work. ‘I’ve Heard Many Things About You’ also resonated with me as a title personally because I have heard many things about this story, but I haven’t been there, I can’t travel back in time, and I haven’t been to Namibia and I didn’t spend a long time in Bremen, so there was that kind of removal as well. Being half Kenyan and half German, it was a way of the Übersee-Museum being confident in allowing me to explore this history even though it is so very loaded, and the point is to generate conversations.

I Have Heard Many Things About You, Städtische Galerie, Bremen 2016.

The veil has a lot of text and a lot of images. During the performative walk I had a flyer that people could also hand out if they noticed someone was really interested. A lot of comments I would hear are people explaining to each other what it’s about. I remember hearing two parent-child conversations happening during my performance. They really reminded me that this is why I do this kind of work, and I think that particular generation, young children in Germany, has the opportunity and the possibility to engage with this topic in a very different way than their parents, and their grandparents, and I think that’s going to be very interesting in the future.

CA: What kind of responses do you get when you take your performance into the public realm like this?

SK: This is the first performance I’ve done in a public realm in terms of streets and I got all sorts of different responses. I told you a few already so that answers some of it, but it was also a sports football league day, so there was a lot of group drinking football fan types and I got a lot of ‘huh, what’s going on here’ and ‘oh really, I don’t want to see this or think about this’. It depends on the tone of voice. I don’t talk during my performances actually, none of my performances have had that framework yet of talking to the public, so I just use my body to engage with people. And I had a lot of people following for a very long time after, in different moments of the walk. So the walk is actually 30 minutes if you’re walking normally, and for me it was maybe about an hour or 40 minutes in the gallery, and the rest of the time was in the street. In the gallery I simply highlight certain texts stitching a line using golden thread, and hanging the installation.

CA: To what extent do research and the colonial/post-colonial archive inform your practise?

SK: The research process is a very strong element in my practise. I often reference and utilise sociological, anthropological, psychological and cultural texts. In my research process I often do interviews with people as well. Yeah, and in terms of working with archival materials, I’ve just done that for the piece at the National Museum in Nairobi and for this work in Bremen. That comes and goes intermittently in my practise.

CA: Your work is rooted in performative production, which in itself is deeply personal and subjective, and I wonder, to what extent is your process and personal narrative fuelled by each other?

SK: I actually use performance as an initiator to change an installation. A lot of my practise is actually sculptural and installation based. I think a lot of the main source comes from a personal base and then gets re-worked or re-layered. A lot of the time I layer a lot. I think there are several ways of hearing and investigating a story, and these experiences are not singular. I think a lot of people experience these things that I work on, which is why people connect with the work.

Not all works originate from the deeply personal and subjective point, so Women, Fräulein, Damsel & Me really did. There were definitely personal links, but the work itself doesn’t remain stagnant in the personal narrative, it’s a very accessible and relatable to the collective narrative.

I Have Heard Many Things About You, Städtische Galerie, Bremen 2016. “….performance as an initiator to change an installation….”

CA: Do you think (performance) art has the capacity to challenge puritanical and patriarchal representations of women, in particular the visual ownership of women’s bodies?

SK: I think all kinds of art have this capacity, I don’t think it’s stuck in the realm of performance work. I think performative actions carry immediacy, and I think performative actions carry immediate connectivity just the way music does, but I think all art forms do this, and can do this, it depends on how you utilise this.

CA: In 2014 you presented the collaborative performance Between Us in Nairobi, examining contemporary viewpoints on themes related to the body, gender issues and social perception. The performance almost takes the ‘subjectivity’ of the performance out of your hands, so to speak, through the presentation of other people’s bodies. Does this affect the meaning derived from your work?

SK: It has actually three chapters, it’s a trilogy. The second phase was performed this year in Dresden, in Germany. It had four performers in total. I think what’s important in this kind of process is to, on my part, is to really develop a frame and then I think it’s very important that people who I’m working with can interpret the frame and input parts of themselves into the work. So there are moments that are very ‘choreographed’ – I don’t have another word, probably I will develop another word, but let’s use that word for the moment – and then there’s moments of interpretation. I think that’s very, very important. When working for Between Us, it was very much a component of that process. I’m very slow and trusting when working with Between Us, because it’s very specific with who I work with and how we work. We spend a long time laying out the groundwork. I ask a lot of vulnerability, we ask a lot of vulnerability from each other and ultimately our audience. I had mentors in both projects, so James Mweu was the first mentor for the first section and Nicole Meyer was the second mentor for the second section. They really take the time to pick a group that really works and I trust them. I have to trust them to do that. So I think that it just makes everything flow really well.

CA: What is your next project?

SK: The ‘Miracle Marathon, Between Loving and Me’ is ongoing, and I’m working on the history of men, men who have been castrated during the colonial times in Kenya. I’m very interested in language, the use of language around torture, and the approval of otherness, the approval of breaking down people, of breaking down and building ideologies. I’m interested in language at the moment, and how words are used in the process of approval or disapproval.