Tell Freedom is a statement in the form of an exhibition. Proof that art itself can tell the story. It is the picture of a generation that knows what it wants and does not want to be fooled with paper promises. The Apartheid may be a thing of the past, the position of many blacks is not yet equal.

Rob Perrée on the exhibition Tell Freedom in Kunsthal Kade Amersfoort, The Netherlands.

FREEDOM HANGS HALF-MAST

Tell Freedom: 15 South African Artists

Haroon Gunn-Salie, VOC Flag, 2017 (photo Mette van der Linder)

The flag of the VOC * hangs on the facade of the museum.

Half-Mast

The tone has been set.

Even before you see the exhibition.

Kunsthal KAdE in Amersfoort (Netherlands) presents an exhibition of 15 South African artists. Unique, because contemporary art from Africa receives little attention in the Netherlands. The relatively small museum takes the lead, as it did before with exhibitions of Caribbean and Brazilian art. The province seems to stick out its neck more often than the Randstad **.

The title Tell Freedom expresses the political charge of the project. It refers to the title of a book by Peter Abrahams from 1954. The novelist left South Africa for England at the age of 20. He wanted to give himself the opportunities that were not available for blacks in his home country. England offered him that. He wrote about a dozen books that remain unknown in his homeland. In 2017 he was murdered in Jamaica (at the age of 97). His death did not cause headlines in South Africa.

Co-curator Nkule Mabaso sees the story of Abrahams as symbolic of the situation now. “(…) the premise of the exhibition takes the connection between South Africa and the Netherlands as a point of critical enquiry; linked to the present day situation of both countries, going in to similarities and differences as to social justice, within a global context, the Dutch settler history in South Africa and so forth…….The artists all selected for their profound historical awareness, continue in this exhibition their on-going attempts to comment on social, economic and political discrepancies as resulting from history, not only to elucidate the present, but question various assumed positions within these two transforming societies.” According to her, although theoretically and legally there is equality in her country, the economic power is mainly in the hands of whites and foreign investors. They ensure that the black African still has no access to that power. For artists, this means that it is virtually impossible to achieve what they want to achieve in their own country. It is not for nothing that successful artists such as Dineo Seshee Bopape and Kemang Wa LeHulere – both included in the exhibition – are successful thanks to their stay and contacts abroad.

*

The artists in this exhibition have been selected for that historical awareness and the way in which this is reflected in their work. The fact that they are all between 20 and 35 years old has on the one hand a symbolic reason – Abraham was 20 when he left his country and 35 when he wrote his Tell Freedom – on the other hand it is the often well-bred generation that no longer accepts the status quo. The student riots that broke out at universities in Johannesburg and Cape Town in 2016 are public proof of this.

Tell Freedom chooses to be political, because the generation in question has the conviction that it is difficult to do otherwise. How urgent can art be?

A political exhibition in which the concept counts so heavily runs the risk of being pamphletistic or inscrutable. Too much theory, too little visual translation. That is certainly not the case and that is one of its best qualities. More often, the works immediately appeal to the emotions and there is a greater chance that the viewer runs the risk of getting too much of it. One of the artists unintentionally puts it into words. When I ask him whether he has already viewed the exhibition himself, he replies somewhat embarrassingly that he had not. “When I walk around I encounter so many traumas … that is too much to process in one go.”

These qualities are certainly also in the work of the individual artists. This selection shows that without doubt.

Haroon Gunn- Salie, Soft Vengeance – Jan van Riebeeck, 2015 (photo Mike Bink)/Zonnebloem renamed – Tennant Street, 2013

The VOC flag is an idea of Haroon Gunn-Salie (1989). In all its simplicity, that work can have the impact that can be compared to the impact that the red-black-green stars and stripes of David Hammons has on black Americans. That flag, made in 1990, has grown into an iconic work of art, which no longer requires explanation. For Gunn-Salie the flag is part of the installation Return of the Amersfoort. The Amersfoort refers to the Dutch VOC ship that deprived a Portuguese slave ship of its ‘cargo’ and moored in Table Bay in South Africa in 1658. Most slaves had died or were thrown overboard on the way. It became the beginning of the Cape as a slave colony. Gunn-Salie has the man responsible – Jan van Riebeeck – reduced to a red wall sculpture: two bloody hands cast from the hands of the heroic statue of him in Cape Town. The documentation of the event – documents, moving images and sounds – is shown in the space behind those hands.

Neo Matloga, Bo mma sebotsana, 2017

Compared to this work, the paintings by Neo Matloga (1993) seem almost airy. In a loose style, he paints scenes from everyday life that will be recognizable in their setting – especially in the objects – for many South Africans, but in their distortions and in the dark colors in which they are executed they point to underlying tensions and contradictions. It seems more like that Matloga calls the ‘happy family’ into question. The figures sometimes also personify famous people as writers and artists. Those are just people, is possibly the underlying message.

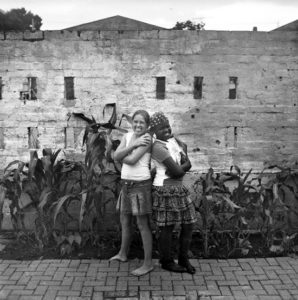

Lebohang Kganye, The Pied Piper’s Voyage, 2013 (photo Mike Bink)

The photographic works by Lebohang Kganye (1990) are also narrative. She has immersed herself in her own family history and has to conclude that there has been a lot of suffering and much has been lost. She allows the viewer to experience this by luring him into a kind of labyrinth that forces him to walk around and be confronted. The arrangement also reminds me of the setting of a large stage. This association detracts the images from the realistic content they may have. In an animation she chooses similar, spatial, stage-like images. Does she play with fantasy and reality?

Sabelo Mlangeni, from the series Big City (2001 – ongoing), Ashley Walters, from the series Woodstock (2016)

I know Sabelo Mlangeni (1980) from his photographs of the gay community in South Africa. In this exhibition he shows images of Johannesburg (Big City, 2001, ongoing), especially of the suburb that is completely deteriorated and offers no perspective (My Storie, 2012) and, by extension, of small cities in South Africa that seem to lack any governmental attention (Ghost Towns, 2012). Because of their format, their documentary style and the choice of black-and-white the photo works don’t seem to be very striking. The viewer who takes the trouble to view them more focused and detailed knows better. The photo works by Ashley Walters (1983) seem to move within the same theme. In his series Woodstock (2016, ongoing), however, he establishes a direct relation with the slaves who, ‘delivered’ by the VOC, were forced to work in that specific area. Descendants are now ‘sent away’ because they do not have the money to pay the housing.

Lerato Shadi, Moremogolo, 2016

Moremogolo (2016) by Lerato Shadi (1979) is absolutely oppressive. On two adjoining projections, the images can be seen of a black woman who eats earth and almost suffocates and the same woman who winds wool around her tongue, making it impossible to talk. The final picture – an unclear figure in a wide African landscape – shows that the work refers to the impotence that the South African experiences when it comes to the still unfair land distribution.

Kemang Wa LeHulere, The Messengers or The knife eats at home, 2015 (photo Peter Cox)

Kemang Wa Lehulere (1984) is currently one of South Africa’s most successful artists. His work is shown internationally. Rightly so, because it is good. The danger is that he falls into repetition. The installation The Messengers or The knife eats at home I have already admired in numerous variations at all kinds of other locations. Car tires and ceramic dogs are central to this work. On the one hand, the tires refer to his childhood when he let them roll with the aid of a stick, on the other hand they refer to the horrible practice of necklacing. The tires, filled with petrol, were pulled over the heads of alleged collaborators and then set on fire. The dogs seem to be symbolic for spectators, in fact for the museum visitor who (passively) looks at a deterrent past.

François Koetze, Cape Mongo – Glass, 2013/Cape Mongo – Plastic, 2014 (photo Mike Bink)

The sculptures of François Knoetze (1989) are built from waste, rubbish left behind, the result of African overconsumtion. On first sight they look like scarecrows, but they are even more frightening because they are designed to engage with the public. In the accompanying videos they do that in everyday situations. It is a cynical comment on a country that is casually focused on consuming and not on learning from the past.

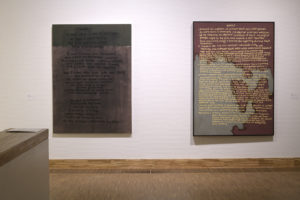

Mawanda Ka Zenzile, White (after Amy Edgington), 2017/Goals, 2017

As I said before, most artists succeed in conveying their message in a visual, seductive, way. A striking example are two paintings by Mawande Ka Zenzile (1986). The first painting is a text by Edgar Hoover from 1967. It states that the FBI wanted to disable politically unwelcome activists, as well as black leaders. On the second painting is a text by Amy Edgington urging white people to take their responsibility for racism. “Do not feel guilty, take action. Guilt is just an excuse not to take action.” In both paintings the texts also function as image and the murky color he uses adds an extra layer of meaning to the texts.

Dineo Seshee Bopape, Lerole: Footnotes, 2017 (photo Peter Cox)

The installations of Dineo Seshee Bopape always move without being completely open. Perhaps it is the combination of images and sounds that are responsible for that emotional reaction. In Lerole: Footnotes (2017) it is a (seemingly) random setting of stacked bricks combined with the sound of water masses and the sound of a bird – Quetzal – of which it is known that it commits suicide in captivity. There are dozens of small sculptures on a few stone stacks. In each country in which this installation can be seen – it knows a number of variants – these are made by a woman of African origin (in the Netherlands this was Chidi Nwosu).

Nolan Oswald Dennis, Azania House (resurrection room), 2017-2018 (photo Mike Bink)

The installation Azania House (resurrection room) by Nolan Oswald Dennis (1988) seems to be a quest of South Africa for his identity. What does it want to be? What had it dreamed of? What has it become? The symbol for that search is the inability to give itself a flag. The country could not come any further than a transition flag. The gray flags in this installation can’t express it better. The computer-generated interpretations of Nelson Mandela’s portrait underline the same identity problem. The battle song Hamba Kahle Mkhono – sung at funerals of people who opposed Apartheid – seems to encourage the country to finally make a clear choice.

Still from Chapter Q: Dem Short-Short-Falls, 2017

On two walls that look at each other, Donna Kukama (1981) projects the recording of a performance she has executed in the Amsterdam Bijlmermeer. On the location where in 1992 an El Al airplane crashed into apartment buildings, she walks, dressed in white, back and forth on a white ‘carpet’ that is rolled out on a swampy surface. Gradually, ‘carpet’ and artist become increasingly dirty. On the left wall the activity can be seen in detail, the opposite wall gives a view from above. Through this performance she rewrites an emotional event in Dutch (black) history. She adds a Chapter Q to her ongoing history project. Because of the way in which the images are edited – sometimes with blank intermediate images and with varying tempos – and because of the addition of natural, but sometimes somewhat amplified, sound, she turns that event into a moving poem that you want to read and reread in peace.

Buhlebezwe Siwani, Batsho Bancama, 2017 (photo Mike Bink)

The most poetic, serene work of the exhibition comes from Buhlebezwe Siwani (1987). A squatting, naked woman is the center of the installation Batsho Bancama (2017.) In front of her is a bowl with a bar of soap in it. She is also surrounded by washbowls. Everything is in a spotty green color. It is a cleansing ritual, but it also refers to the position of the African woman and evokes memories of the colonial past (the bowls of enamel were the standard tools of the African housemaid). The whole looks like a tableau vivant, a ‘frozen’ moment in a moving story.

*

Tell Freedom is a statement in the form of an exhibition. Proof that art itself can tell the story (a tip for the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum that is preparing a large slavery exhibition). It is the picture of a generation that knows what it wants and does not want to be fooled with paper promises. The Apartheid may be a thing of the past, the position of many blacks is not yet equal.

KAdE may be praised for presenting such an exhibition at a time when African art in general, and the engaged variant in particular, is still not given an honest and fair place in the Dutch art world.