The African American artist Terry Adkins died in 2014. At 60. He was hardly known outside of the USA. Even at home his work did not get the attention it deserved. At the moment – until June 11 – Paula Cooper Gallery in New York presents work of Adkins. Finally. A good reason to re-publish the article Rob Perrée wrote about his work in 2018.

Native Son, 2006-2015

Terry Adkins (1953-2014)

MUSIC MADE VISIBLE

1.

I met Terry Adkins in 1995 in New York. I was more or less sent by a fellow artist of his. Not only because I had to see his work – “there is no better artist” – but also because he could provide me with the necessary information and contacts for the exhibition that I was preparing at the time.

This was not an exaggeration. I did not understand much about his work at that time but the person was extremely amiable and helpful. His loud laugh sounded long after the visit had ended.

2.

In 2015, the Nigerian Okwui Enwezor was the curator of the Venice Biennial. He had selected a lot of work by black artists. Terry Adkins – the year before he had suddenly died, 60 years young – was honored with a large number of works that, as a coherent installation, occupied the space and unavoidably captured the viewer. An orchestra awaiting his conductor. An impressive tribute. For many visitors it was their first acquaintance with his work though.

Installation Views, Venice Biennial, 2015

3.

With an artist friend, in 2016 I visited a David Hammons exhibit in New York City. An overwhelming, emotional experience. Afterwards we wanted to blow off steam in a much too expensive – Upper East Side, we should have known – coffee shop. In our conversation the superlatives tumbled over each other. While discussing and gesticulating, we came to the question which African-American artist was at the top of our list. I hesitated between David Hammons and Kerry James Marshall, she immediately said “Terry Adkins. No doubt about it.” Her certainty made me doubt.

4.

Why is it that Adkins has remained unknown to many art lovers, especially those in Europe? Why did the real attention to his work manifested itself only after his death?

Muffled Drums, 2003-2013

5.

Terry Adkins (1953-2014) was born in Washington DC. He spent a large part of his childhood in Alexandria, Virginia. He comes from a Catholic family with 5 children. Terry was the youngest. His parents were in education and were amateur musicians. As a child he found out that he could draw well. In 1971 he enrolled at Fisk University. In the second year he switched to the art department. That the artist Martin Puryear taught there undoubtedly played a role in that decision. At graduate school he chose sculpture and printmaking. It was a challenge for him to assemble existing, found materials in such a way that they got a new life. “The functions of these materials fascinated me. They were discarded as being useless. So the idea that they could be rejuvenated and repurposed was exciting because it taught me how to identify those things that had potential for something. Certain things had to be to themselves.” Because he has been playing sax and other instruments for years now and was a member of a jazz orchestra, music and art became increasingly interwoven. He made his assemblages “as immediate and ethereal as music. And the music I pursued, I practiced visceral and physical-almost approaching matter. Trying to do both is not a challenge. “

Methane Sea, 2013.

6.

Because he opted for materials with a past, it seemed obvious to Adkins to also choose history as a theme. From the very beginning of his career, he knew he did not want to make representational art. He found that kind of art conservative. In his last interview – in Bomb Magazine – he put it like this: “(…) what I mean is that it keeps it at the level of the social realism of the 1930s and, in that sense, it’s really conservative I don’t see anything advancing further than what they did in the ’30s, even though it might have been a contemporary subject matter, like this romantic image of the ghetto. But you know it is also about trying to set the stage. I still consider it to be a big impediment, and that is why I have always chosen to be abstractly, to deal with the principles of what I have achieved”. In order to reinforce his words, he quoted Earl Hooks as the chairman of the art department at Fisk University.” (…) when at Fisk I asked how much should I let blackness influence my work. He looked at me inquisitively and said, “Do you really think that we are the only people to be fucked over?”

Choosing abstraction and choosing abstraction for this reason have undoubtedly influenced his recognition. Abstract working artists such as James Little and Sam Gilliam also know from experience how difficult it is to get that kind of work presented in ‘the circuit’. Work by a black artist should make blackness visible. According to many .

7.

In the eighties, when Adkins came to New York for a residency at the Studio Museum, it was not strange that artists expressed themselves via different disciplines. You could be a painter, but at the same time play in a band (Penck), give performances, write for an art magazine (Barbara Kruger), or even write fiction (Richard Prince).

That new freedom did not last long. Ten years later everyone had to be back in his or her established ‘box’. The ‘Neue Wilde’ (that is how these Neo-Expressionists were called in Germany) were tamed again. That made it difficult to position Terry Adkins. Was he an artist? A musician? A composer? A performer? He consciously chose this versatility because for him there was coherence within that versatility. This was thought to be difficult by many viewers, including professional ones. Add to that that he was not very fond of the gallery system, to put it mildly. If he worked with a gallery, then it would have to be a young, experimental one (LedisFlam in Dumbo, New York for example). That complicated his position, his status as an artist even more.

For a while he also made installations in empty buildings. In the early nineties, for example, after his son was born. “I had time for my family, for my son growing up. That is when I started doing these things in the abandoned buildings. I would just set them up. [Terry would set up installations or found materials in abandoned buildings and photograph them.] Leave them, take a picture, and boom. I did not care whether it got into the gallery system. I was frustrated by the gallery system. And so that is when the Visionary Recital project starts and stops at the site and makes the quick immediate gestures, moving through the space. Taking the pictures. I did not care whether the pieces were going to be destroyed or not because they ended up being destroyed. Often time, I had to employ strategies that involved being one of the workers in the daytime to see what was in the building, leaving just the right through cracked open enough to get back in at night. Do these things overnight, take the pictures, and then leave. “

A pleasantly stubborn way of working, but not the way to become a well-known and recognized artist.

8.

Darwater Record, 2003

In 2003, Adkins created Darkwater Record. A stack of 5 black tape recorders with, in white, the porcelain bust of Mao on top. The work refers to a speech by W.E.B. Du Bois. Who was a sociologist, historian, important voice during the Harlem Renaissance and, later, for the civil rights movement. In 1960, he gave a speech about Socialism and the American Negro. On the pointers of the recorder you can see that there is sound, but because the speakers are missing, the visitor does not hear it. Du Bois is no longer heard? Is that the message?

This is a characteristic work by Adkins. It pays attention to heroes from the past who have played an important role in the history of the African American. “Enigmatic figures like John Brown, John Coltrane, Sojourner Truth, you know, Zora Neale Hurston.” He does that in an abstract way. Image and (in this case the suggestion of) sound are interwoven.

Naitive Son (circus), 2006-2015

Native Son refers to the book by the American author Richard Wright, a novel that paints the ugly face of racism. It is a stack of partially overlapping cymbals that make jazz-like sounds at random moments. A harmonious whole that wants to contrast with the ‘unbalanced’ content of the book.

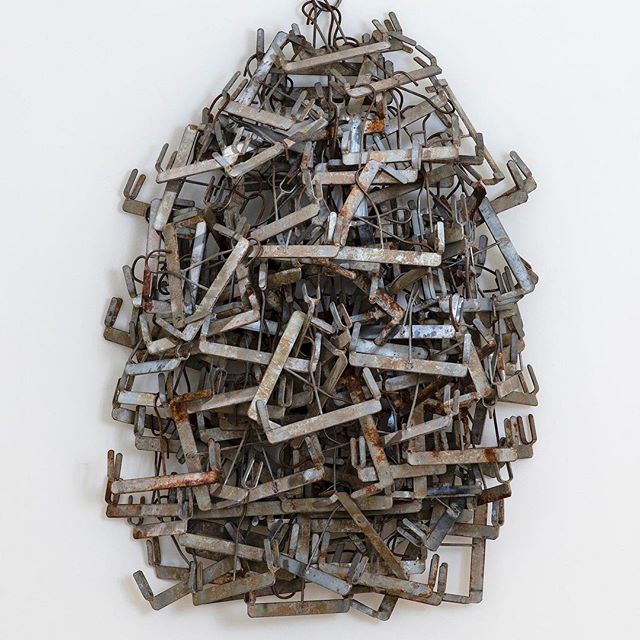

Matchbox Blue, 2003

Matchbox Blue is not only a good example of reviving existing material by using it in a different way – some rusty meat hooks that yields a solid shape together – but above all an example of reviving the past, retrieving memories that are about to disappear. The work is a tribute to early blues musicians who have had a lot of influence on today’s jazz greats. Matchbox Blues is the title of a Blind Lemon Jefferson song (1897-1929). The form refers to those blues musicians as being a group, a whole, a unity: they did not make any money, but they kept making good music.

Columbia, 2007

Because Adkins abstracts, it is sometimes difficult to figure out what a work is about. In this work the association with an LP can be made quickly, especially by the title. That it refers to Bessie Smith (1894-1937), a singer who was very poplar in (black) America in the thirties, is far less obvious. The layered blackness of the work could indicate/refer to her skin color combined with her early death. But that seems like pure speculation.

Last Trumpet, ongoing

Adkins often performed as a musician in the very setting of his works. He was then mostly assisted by the Lone Wolf Recital Corps, a versatile group of musicians who expanded the performance into a true concert. Knowing that they often played Adkins’ compositions, it is not strange to conclude that the boundaries between the various disciplines were completely abolished on such an occasion.

Omohundro, 2002

The title could refer to the name of a slave trader from Richmond. Music and the south go together in a natural way, but this instrument is silenced. It has become a captured form.

Aviarium, 2014

Aviarium is one of the last works of Adkins. It was shown in the Whitney Biennial (2014). It consists of cymbals of different sizes that are pushed over aluminum bars. Artist Ken Lum called it “a visually appealing embodiment of musicality”. The work is reminiscent of musical instruments and perhaps also evokes the sounds of it, but it hangs completely silent above your head.

9.

At his death , it became clear how important Terry Adkins had been to others, students but also fellow artists. In an article by Sarah Goffstein, Charles Gaines said: “He was very interested in raising the profile of people, because he thought he had a certain weight or under-representation,” Ex-student Sanford Biggers put it like this: “In some ways he was a model of how to be in this world. As an African American male dealing with subject matter that people in the art world had no knowledge and no interest in aspects of history that have purposely been occluded and marginalized. “

In interviews, Adkins tended to say in a somewhat relativistic way that he was teaching to support his family. That obviously played a role, certainly because there was no broad recognition of his work for long period of time, but the reactions from his environment show that he not only materialized his inspiring, original ideas in his work, but also successfully passed them on to his students and colleagues.