The coloring book and existing fairy tales may be his most important inspiration, but there are more influences. His work is a tribute to folk art because of the imagery, the setting and the absence of nuance. It also refers to the comic book tradition. When you see a presentation of Bankston’s work, it reads like a comic strip, it reads like a coherent story with a scene on every page. With one big difference: the viewer has to ‘write’ his own text.

Rob Perrée on the work of John Bankston

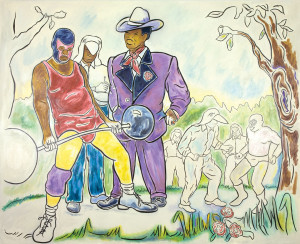

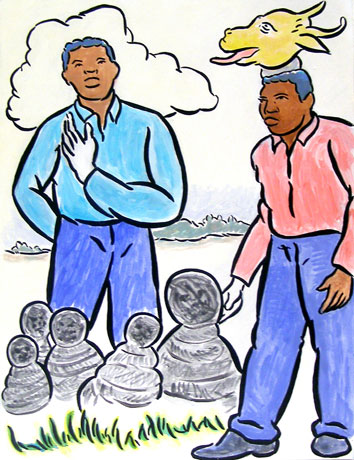

Give and Take, 2006.

THE GAY STORIES OF JOHN BANKSTON

“Storytelling, perhaps the best-known oral tradition of African American culture, exemplifies the desire to express oneself and convey a sense of heritage. The experience of slavery actually enhanced, rather than destroyed, oral traditions for African Americans. Telling stories was one of the few ways enslaved persons could communicate memories of the African homeland, along with tales of hope and resistance. Then, as now, the storyteller was an important person in the community who could transform listeners by sharing new values, norms, customs, and perspectives about the world in which we live. “

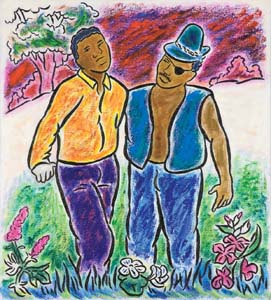

Man’s Country I, 2004.

For a long time storytelling was hardly visible in contemporary art. It was considered superficial, too easy and too close to reality. In a Modernist art world where ‘the concept’ was reigning there was no room for narrative art. Figurative art in general was relegated to the lower regions of the art strata.

That situation changed.

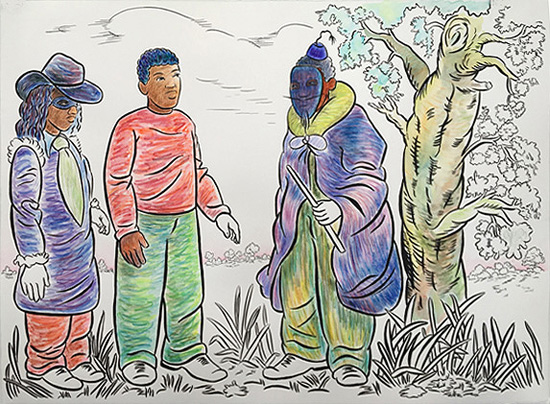

Beginning or End, 2006-2007.

There are several reasons why storytelling is back in the arts. I don’t want to go into the detail of why this is the case, it is not the subject of this article, but I want to quote one remarkable possible reason. I read it in the text that went with the ‘Storylines’ exhibition last year in the Guggenheim in New York: “The recent narrative turn in contemporary art cannot be separated from the current age of social media with its reverberating cycles of communication, dissemination, and interpretation. Seemingly every aspect of life is now subject to commentary and circulation via digital text and images. These new narrative frames highlight the roles that each of us can play as both author and reader, foregrounding the fact that meaning is contingent in today’s interconnected and multivalent world.” (1)

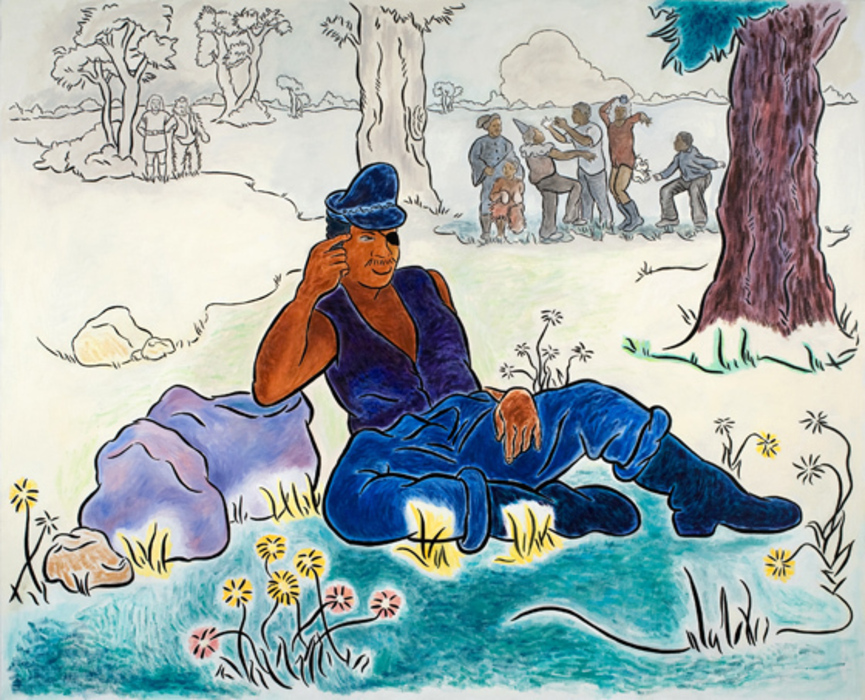

Switch, 2011.

I don’t know if the African American artist John Bankston (Benton Harbor 1963) played a role in the renaissance of narrative art. Since he started his career twenty years ago it is fair to call him a pioneer. It took a while though before his work attracted attention. Now it is popular among a growing group of art lovers and collectors. Solo shows in museums are not yet the case, but his work has been presented in many important group shows, a prime example being ’30 Americans’. (2).

Mysterious Meeting, 2014.

I saw his work for the first time in 2001, in the exhibition ‘Freestyle’ in the Studio Museum in Harlem. At first sight the paintings looked like old fashioned fairy tales carried out in a simple way. This first assumption soon proved to be a misunderstanding. The main characters were black, the stories were erotically charged and the scenes were very funny. All features that are not commonplace. My fascination was fueled.

Delivered, 2015.

John Bankston is African American, gay and lives in San Francisco. Normally I don’t want to bother the reader with this kind of trivial, Vanity-Fair-like information. With his work however it makes sense. This background is visualized in his paintings and drawings. It makes them intriguing, layered works of art.

Like every child Bankston liked coloring books. Later he realized that most of these books had only white characters. “When I was growing up, I saw very few African Americans of any sort in coloring books. Using coloring books is something we all have in common. It is our first experience as visual creators.” (3) Later, as an artist, he decided to take the main characteristics of a coloring book as a starting point. The black lines define the forms and they contain the colors. He colors the forms in the same way as children do: irregular and bright. ‘Big Flower’ (2013) is a good example of this technique.

Big Flower, 2013.

Every work looks like a scene out of a fairy tale. They remind you of fairy tales out of your childhood, but also of other children books – whether or not read by one of your parents – and even of slavery narratives. The presence of Winnie the Pooh is felt, Frederick Douglass is nearby, Grimm is whispering on your shoulder. This familiarity is confusing. It is merely meant to draw you into the story. Then you realize that the fairy tales are different. They are populated by men only, gay men, black gay men. Very rare in this genre, a statement in itself. Most of the time they are dressed up: as cowboys, as pirates or magicians. Or they are dressed in leather, in uniform or with rabbit ears. It is more than just a big role-play, it is about men living out their fantasies, it is playing with their fetishes; it is playing with their identity and perhaps even looking for their identity.

Bankston’s ‘creations’ are inspired by San Francisco. “I’m more interested in the way adults present themselves through performative dress. San Francisco is a great place to witness this. We’ve got pirates, cowboys and nuns with beards on the street, and that’s just in a three-block radius.” (3)

Mid Day Idyll, 2007.

The location in which the men live their fantasies is far from urban however, it is rural and woody. Some say, a ‘Caribbean flora’. Bankston calls it the ‘Rainbow Forest’. By doing that he makes it impossible not to think of cruising area’s where gay men meet, talk, play, seduce, have sex. In many works there is a foreground scene – an innocent conversation for instance – that ‘hides’ a more suggestive scene in the background. Sometimes not in color, as if it does not count or is at least less important.

The Letter, 2013.

Does that mean that Bankston is a kind of black Tom of Finland? Not at all. By using the ‘language’, the imagery of a coloring book he gives his fairy tales an innocent, sometimes even a vulnerable edge. His scenes are playful, merry making, gay in the old fashioned meaning/ sense of the word. The erotic touch is not more than a modest undertone. If the drawings of Tom of Finland are arousing, the works of Bankston make you smile. If the work of Finland is explicit, Bankston triggers your fantasy and makes you think and wonder. It makes you think outside of your own territory.

Aria, 2010.

The coloring book and existing fairy tales may be his most important inspiration, but there are more influences. His work is a tribute to folk art because of the imagery, the setting and the absence of nuance. It also refers to the comic book tradition. When you see a presentation of Bankston’s work, it reads like a comic strip, it reads like a coherent story with a scene on every page. With one big difference: the viewer has to ‘write’ his own text.

Magic Hat, 2015.

Another significant influence must have been the self-taught Henry Darger (1892-1973), the father of narrative. His work was one big fairy tale, a seemingly endless fantasy of blond girls playing around in a rural environment, carried out in an elementary style, not bothered by the rules of perspective and depth.

Perhaps the most important influence however comes from Bankston’s own cultural background. African Americans have a long tradition of storytelling. The content of his ‘stories’ is an original actualization of that tradition.

Courtesy: walter maciel gallery

2642 s. la cienega boulevard

los angeles, ca 90034