“We invite them to tell their story, to share the photos with the audience.“ Harris is present to direct the event, but the floor is for the people. They talk, they respond. “They want to listen with their heart. They want their hearts to be open. There is no fear.”

*

Rob Perrée interviews the American filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris about his latest film “Through a Lens Darkly’ and his ‘Digital Diaspora Family Reunion’ project.

The latest projects of filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris

‘BECAUSE I AM THERE, SOMETHING HAPPENS’

In 1995 I saw the first feature-length film of Thomas Allen Harris (The Bronx, 1962): ‘Vintage – Families of Value’. His brother, the artist Lyle Ashton Harris, had invited me. Through the eyes of the gay brothers the film looked at the importance and the character of values in black American families. ‘Vintage’ was shown within the context of a gay film festival in the East-Village (New York). A home game. It was a special experience for me because Harris’ film was very personal, his images were not slick or deliberately beautiful, the editing was far from perfect, but as a whole the film made, because of these non-artificial characteristics and because of its integrity, a deep impression on me.

Still from ‘Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela’, 2005 (The Twelve burn their passports)

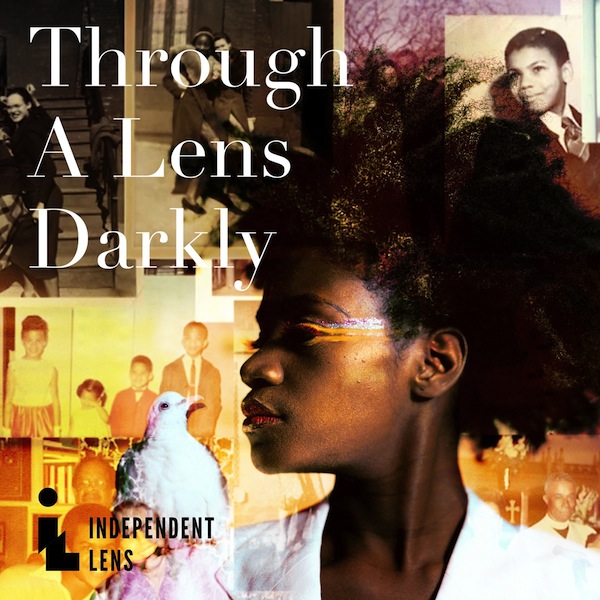

Last year the 4th experimental film of Harris was presented: ‘Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of People’. The context: the prestigious Sundance Film Festival. The film explores how African American communities use(d) photography to create their own representations and, by doing that, to correct the conventional (white) representations that people are more accustomed to seeing in mainstream media . “From the very beginning photography was used as a kind of a weapon, either for or against the enslavement of African Americans. And that continued with each decade to the present day”, says Harris in a television interview. (1)

Through a Lens Darkly (still, features collage of works by Michael Chambers and Lyle Ashton Harris)

‘Reflections in Black. Black Photographers from 1840 to present ’, a book of Deborah Willis, was the inspiring force behind ‘Lens’. The basic form of the film is traditional: interviews illustrated by images. But the film is more. Like all his work, ‘Lens’ has a strong personal touch. The beginning sets the tone: Harris tells how his father wiped Vaseline off his face to avoid that people would think “that you are a greasy monkey”. All through the film the voice-over makes personal remarks as a kind of underlying commentary. The interviews with artists, historians, scholars and photographers are interspersed and illustrated by almost a thousand photos, professional photos but also many touching photos from family albums of average African Americans. Personal witnesses of private black lives. A hidden history coming out. With the knowledge and the experience of recent incidents you could also say that they are illustrations of the slogan ‘Black Lives Matter’. “In the film I surrounded myself with family, so to say. I needed family. Especially as a gay man. My brother and I are tolerated and loved by the family, but there is a gap.”

‘Through a Lens Darkly’ is a success. The work is touring, inside and outside of the United States. A successful Ethiopian presentation was recently completed.

One of the reasons why the film used so much private material is because a lot people feel the need to show their photos to Harris. Without being asked. “I feel like what I am doing is healing. They want to share, they want to be validated. They want to tell their stories, because their stories are not told. Out of the story-telling tradition of Africans and African Americans? That could be. But you have to realize, many black families had to leave the south in what has been called ‘The Great Migration’. Stories are the only ‘things’ left, the only ‘things’ they could take with them. That makes them potent.”

To give an infrastructure to the ritual of handing of photos, talking about them and listening to all the stories that go with them, Harris and his partner started the ‘Digital Diaspora Family Reunion’ (DDFR) in 2009. In the beginning only a website functioned as the platform ( 1world1family.me), now the family reunions often take place on location. Sometimes together with a screening of ‘Through a Lens Darkly’, sometimes as a onetime event of 90 minutes, sometimes as part of a weeklong artist in residence program. In general institutions invite him to present the DDFR. They take care of the organization and the public announcements , the PR, Harris fills the event in with his staff of photographers, musicians and specialists. People bring or deliver their own photos. “It helps them organizing their own archive, because I ask them to pick out 15 photos that are the closest to them. They have to create their own narrative. “ Harris scans the photos, puts them on line (on the website or on Facebook, “A virtual museum”) and projects the images on the wall or on a large screen, when on location. “We invite them to tell their story, to share the photos with the audience.“ Harris is present to direct the event, but the floor is for the people. They talk, they respond. “They want to listen with their heart. They want their hearts to be open. There is no fear.” The whole event is taped. “I want to do something with the material. Perhaps another film, or an installation. Perhaps I recreate the images with actors. Make a film where fiction and non-fiction are intermingled. Or I make a television show. I don’t know yet.” All the reunions are different, because the people influence each other . The stories go back in time, sometimes far back. “In fact these reunions are a deconstruction of the documentary praxis. There are characters, there is a story, there are images and there is music.”

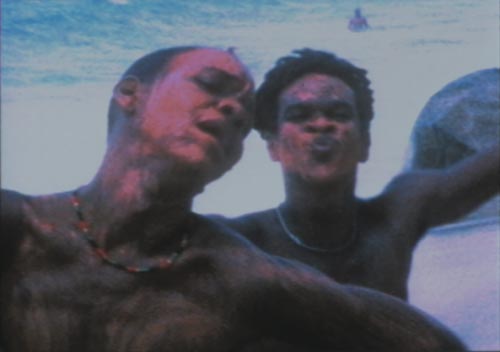

Still from ‘Vintage – Families of Value’, 1995 (Brothers)

Thomas Allen Harris started in the 80’s as a photographer. He is still making photos, but he needed a bigger canvas. Film can give him that canvas. At first glance it may look as if there is a difference between his activities, but they have a lot in common. “I provoke something. Because I am there, something happens. I make the story. The book of Deb Willis is in itself no film. It needs investigation. It needs a form. My father’s archive was there, but it had to be activated. I am in it, doing it. There is always a certain urgency, that’s true.”

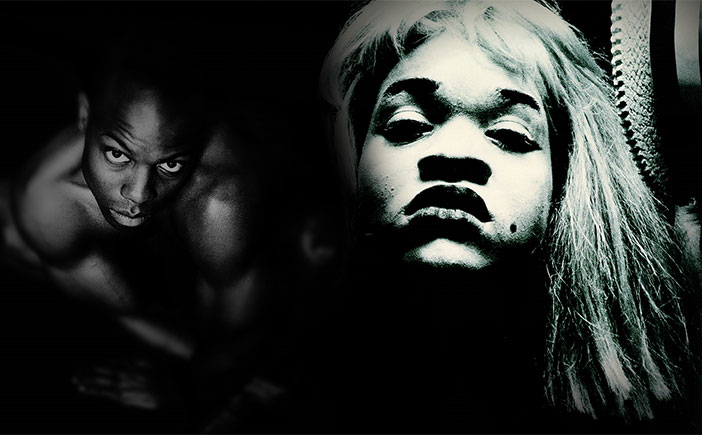

Still from ‘Through a Lens Darkly’ (photowork of Lyle Ashton Harris), 2014 (1987/1988)

During my conversation with him he corrects me several times. “I never call my films documentaries. I use the word film, experimental film. Form is very important for me. Every project is a formal investigation in the first place. I don’t want to choose between form and content, that is like choosing between your two kids, but to a certain degree the form of a film dictates the content. Form creates content. Don’t take me wrong, my films are about freedom, about humanity, about community, about where-are-we-now? These are all important subjects. But I am an artist. I want to create.”

Still from video installation ‘AFRO (it is just a hairstyle)’, 1999.

In 2011 Harris presented one of his rare installations at the Long Beach Museum of Art. ‘AFRO (is just a hair style)’. He brought together images he shot in three public spaces, locations that had played a significant role in his life. The moving images were in itself impressive, but the dialogue between the images, between the three worlds, made the installation an inspiring viewing experience. Especially because I, as a viewer, was in the work. It surrounded me. Every time I see him I remind him of this work and try to convince him to make more installations. And by doing that, to reach another audience.

Perhaps it will happen now, with the rich footage out of his Family Reunion project.

*

1. An interview with Amy Goodman of Park City TV in Utah. All the other quotes are the result of a conversation I had with Thomas Allen Harris in October this year.