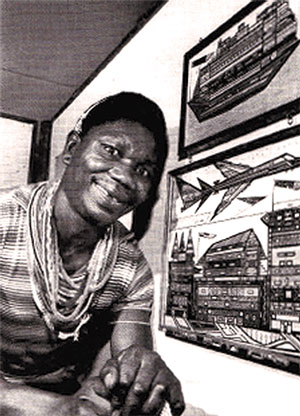

This work of Tito Zungu is part of the exhibtion ‘How Far – How Near’ in the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Till Februari 1.

Tito Zungu

Tito Zungu was born somewhere between 1939 and 1946. He was born in the Thukela valley, Maphumulo in KwaZulu-Natal. He never acquired a formal education. He was like so many others of his time.

He worked on a farm as a labourer between 1957 and 1966. His love for the land permeated his entire life and defined the way he lived. He was a subsistence farmer and an artist. Visits were always prefaced by lengthy discussions about mielies, donkeys, goats, weather, and then art. He held a brief job at a dairy in Pinetown, just outside of Durban. In 1970 Zungu moved to Durban to work for the Dominican Order as a cook. It is there that he began his artistic life which was tentatively encouraged by the nuns.

1977.

1977.

Zungu had a prolific memory which he often referred to for subject matter in his drawings. The lyricism of his work, due to his acute storytelling ability was often at odds with our rational, driven society that pedalled fact rather than memory. He taught me a lot with his gentle manner, instructing and reminding me of the relevance of respect as opposed to power. He once said to me: “I have nothing to offer you as I am a poor farmer so I will ask Jesus to give me his brightest star to offer you as a token of my thanks”. It is exactly this sense of illumination and generosity that informed his creative and artistic temperament; a man with little material valency but eternally wealthy in all that which emanates from the human soul.

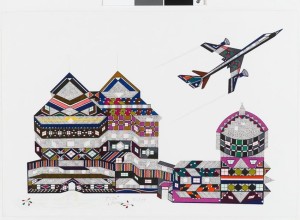

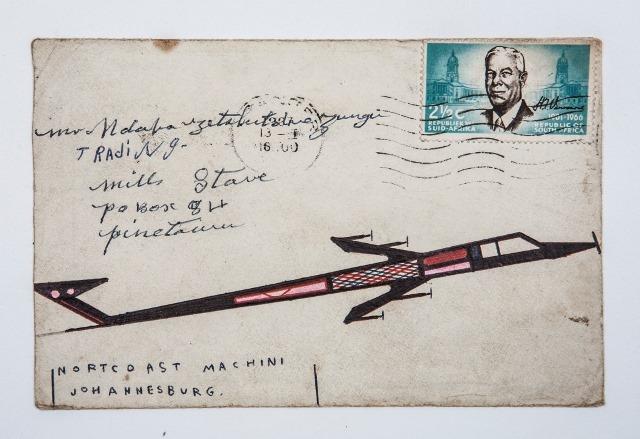

He recalls that it was in the 60s that he began to decorate envelopes which he said he sold for 50c to migrant workers who needed to send home “special” letters to their families and loved ones in other parts of the country. The metaphor of the envelope, its shape, its function as a carrier of both intimate and pragmatic information thus becomes a metaphor of Zungu’s preoccupation with the idea of flight and distance, not only of fantasy, but also as the vehicle for important information.

When he began to communicate his emotional intentions, especially those which began to frame his courtship rituals with his wife, Ngethusile Gloria, the envelope and the letter became the spine of his artistic oeuvre.

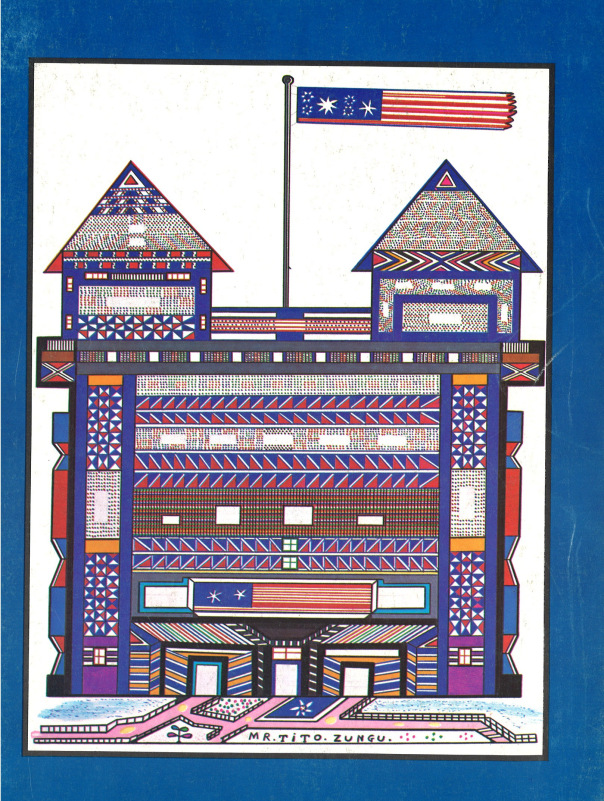

As a strictly traditionalist Zulu, his emotions were always formally and tidily expressed, clear, unequivocal, yet powerfully supported by the lyrical, jewel-like qualities of the drawings on the envelope, that which imbued the love letter with a renewed and potent force. The significance and relevance of the traditional beaded Zulu love letter, which is given by the woman to the man as an encoded message of love within the traditional courtship ritual, informed Zungu’s artistic provenance. He spoke to me of the significance of these love letters he penned and decorated as part of his migrant worker courtship ritual and yearning.

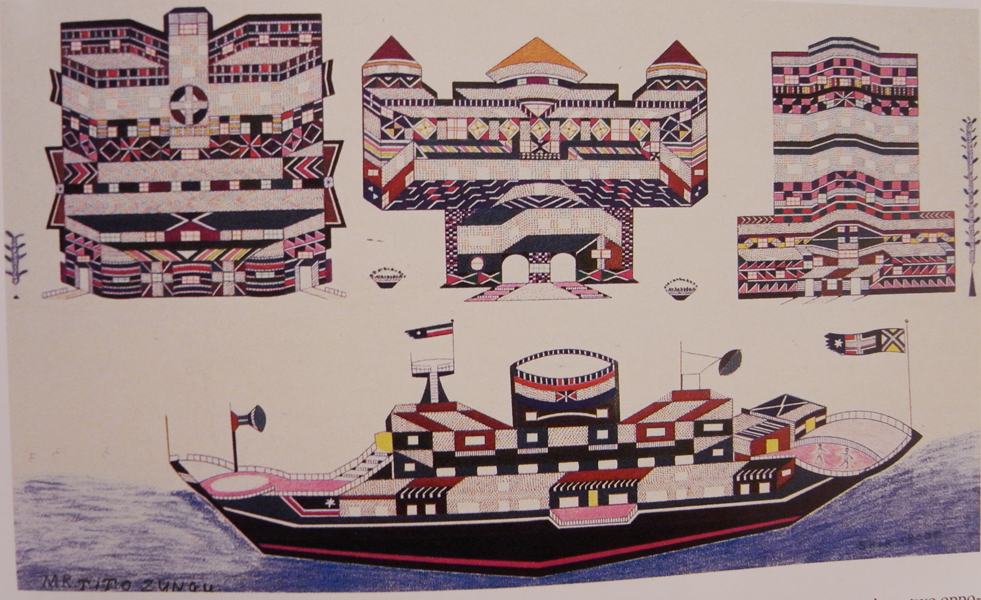

These early letters and envelopes were drawn with ballpoint, and, in due course, they would fade. In retrospect it is significant and perhaps relevant that these early musterings of creativity and love should, in time, simply fade. It would seem inappropriate to have expected Zungu to have been conversant with the concerns of conservation. Increasingly these faded ghost-like images carry a greater poignancy in the light of a life neglected. His envelope creativity affirmed his fascination with technology; aerial, road and marine transport, the conduit whereby a body or a thought could be transported through space and time to be lodged at a distant place that could not be seen but could still be the receptacle of one’s intimate thoughts. This idea of the ability to transcend physical space and time somehow becomes the conceptual canvas which frames the significance of Zungu’s work.

On my first flight to Amsterdam with Zungu he kept coming to fetch me to show me the small little aircraft captured on his video screen in front of his seat, indicating to me how wonderful God actually was. This was Zungu at his best, teaching me to look again at things that I had taken for granted.

He met Jo Thorpe, the late Director of the African Arts Centre in 1970 and showed her his decorated envelopes. She was immediately enthused and became a persistent patron, not only of Zungu himself but also of his work. It was largely due to her industry that Zungu became known in South Africa for his envelopes and then later for his larger drawings which began to be patronised by selected buyers in the South African and International art market.

Dr Ronal Lewcock of the University of Natal, Department of Architecture, as well as Professor Pancho Guedes of the University of Mozambique and then University of the Witwatersrand, Department of Architecture also added their voices and assisted in spreading the provenance of Zungu’s creativity. But it was Jo Thorpe who became his strongest, loyal and most persistent advocate.

1969.

1969.

During the 1980s and 90s Zungu gained further prominence in the South African and international art arena. He participated in a number of exhibitions and appeared in several publications including The Neglected Tradition – towards a new History of South African Art (1930-1980), The Art from South Africa Exhibition (MOMA, Oxford), the 1991 Cape Town Triennale and the Venice Biennale in 1993. In addition to this Zungu has also received many awards. His work was also represented in South African and international collections.

Zungu continued working until a few weeks before his death.

Pancho Guedes in his opening address of the 1982 Retrospective Exhibition at the Studio Gallery, Senate House, University of the Witwatersrand, said: “There are two kinds of art, the cooked and the raw; the pastiche and the original. The cooked kind is made through forced feeding at art schools; it riffles the baggage that others has already carried; it hides its head in the sands of techniques; it progresses incessantly by eating its own tail; it fills the galleries of the world with comfortable reproductions. Raw art is the art of authentic artists who have a compulsive need to communicate their own visions; it does not get around on crutches; Tito Zungu’s art is bright and joyful – startling and raw.”

As a postscript I wish to recall one particular occasion when I had taken an international curator to meet Zungu as she had wanted some of his drawings to be exhibited in the Pompidou. It was interesting to me how elegant Zungu was in all of his human transactions. Business was never discussed without the customary formality of salutations, the patient circulating around the small details of life, children, loved ones, and the weather. We would eventually arrive within the ambit of the transaction; he would always honour the guest and those who had made the meeting possible. It was humbling to witness the manner in which he formally valorised another’s life before dealing with his own needs. He turned to me and simply said in Zulu: “Andries, it is now your turn to talk about my business”. I explained to him the necessity of signing a contract, what it meant and what the consequence of the loan agreement would be. He listened patiently, nodded his head and then simply said: “Where must I sign?” It was one of the few things he could write. He signed the document: Mr Tito Zungu.

We then progressed to his studio. Inside I was once again surprised by the clutter, confusion and poverty. His small desk next to the window was a disarray of pencils, paper, tobacco boxes, various plastic packets, Rizlas, newspapers flecked with little black spots that looked like small pieces of insect faeces. He delicately brushed all of this aside, intuitively navigating his way through the confusion, pealing back a number of pages of newspapers. The confusion began to unwind into order until eventually near the bottom he revealed the secret of a mosaic-like poem; a spotless jewel-like drawing, clean without a blemish. We made the selections for the Pompidou. They were then delicately rolled up, sealed again in various pieces of paper, then newspaper, then plastic bags: Checkers, Pick and Pay and Game, stuck together with masking tape and sealed at either end. We left with Zungu leading the entourage towards the tributary of the Tugela. The river and the crossing thereof is another story, suffice to say this is a fragment of Tito.

Andries Botha

Go to Gallery

1. Thorpe, Jo. 1994. It’s Never Too Early: African Art and Craft in KwaZulu-Natal, 1960-1990. Indicator Press: Durban.

(From ‘Revisions. Expanding the Narrative of South African Art)