Tony Gleaton, 67, Dies, Leaving Legacy in Pictures of Africans in the Americas

By BRUCE WEBER

New York Times, AUG. 18, 2015

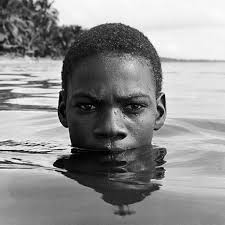

Un-Hijo-de-Yemaya-Hopkins-Belieze, 1992.

About:

Tony Gleaton, a photographer who turned his back on a career in New York fashion and embarked on an itinerant artistic quest, documenting the lives of black cowboys and creating images of the African diaspora in Latin America, died on Friday in Palo Alto, Calif. He was 67.

The cause was oral cancer, his wife, Lisa, said.

Mr. Gleaton made his photographs in the American West and Southwest, and then, most prominently, in Mexico, where he lived among little-acknowledged communities of blacks — descendants of African slaves brought to the New World centuries earlier by the Spanish — in villages on the coastal plains of Oaxaca, south of Acapulco.

Barbershop, 1990.

An exhibition of those photos, “Africa’s Legacy in Mexico,” which appeared in galleries around the country for more than a decade beginning in the 1990s, was sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution.

Mr. Gleaton specialized in black-and-white portraits, their subjects — children and adults, alone or in groups — almost always in direct engagement with the camera and usually in tight frames that suggest but do not explore a specific setting, like a workplace or a barroom. In an interview with The Los Angeles Times in 2007, he called his pictures “abstractions from daily life,” saying “they may look natural but they are extremely crafted, very calculated.”

“This is not journalism,” he added. “I am making art.”

Daughter of Jesus, 1988.

The images he captured — or, better, created — cannot be called intimate so much as defiantly vivid, as if Mr. Gleaton were helping people emerge from obscurity, allowing them to announce their very existence. Indeed, this was his stated purpose.

“These are beautiful photographs of people who are not normally portrayed in a beautiful way,” he said.

Leo Antony Gleaton was born in Detroit on Aug. 4, 1948. His father, Leo, was a police officer; his mother, the former Geraldine Woodson, taught school. In the late 1950s the family moved to Los Angeles, where Tony graduated from high school.

He enlisted in the Marines and served in Vietnam; when he returned, in the early 1970s, he enrolled at the University of California, Los Angeles, where his interest in photography was sparked. He also attended the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena and the University of California, Berkeley, though he never earned a bachelor’s degree.

The beloved of Aphrodite, 1990.

He spent three years in New York, working as a photographer’s assistant in the fashion industry and taking pictures for Details and other magazines before deciding that there was more meaningful work elsewhere.

He was in his early 30s, and he began hitchhiking, ending up in Nevada, where he took pictures of Native American ranch hands and black rodeo riders.

Plumbing the culture of nonwhite cowboys, he traveled to Texas, Colorado, Idaho and Kansas; his show “Cowboys: Reconstructing an American Myth” appeared in galleries in Oklahoma, Nevada and California. His years of traveling and photographing in Mexico began with an interest in Mexican rodeo.

“One of the interesting things about Tony was that he could do more with less,” Bruce Talamon, the executor of the Tony Gleaton Photographic Trust, said in an email. “By that I mean as we live in a time of celebrity photographers with big budgets, and untold numbers of assistants and stylists, Tony would have a small bag with one medium-format camera, one lens, $5 in his pocket, and a few rolls of Tri-X film.

Untitled (Peru), 1995.

“He always shot in available light. He could find beautiful light everywhere he went.”

For his trips to Mexico and Latin America, Mr. Talamon said, Mr. Gleaton “would buy a one-way ticket on a Greyhound bus.”

“These were self-financed trips. And because he was on a budget, he had figured out that there was always a spare bed at the village church, and that was good for at least five days. He would offer to work for meals and then, based on the priest’s introductions, he would start to photograph, staying for a few weeks, and then he would return home with magic.”

A big man — he was well over 6 feet tall and weighed more than 300 pounds — Mr. Gleaton was known as a charmer, especially with his subjects and with students of photography. He was divorced three times before he married Lisa Ellerbee, a teacher, in 2005. She is his only immediate survivor. They lived in San Mateo, Calif.

Mr. Gleaton, who was light-skinned with green eyes, said he often had to explain to people that both his parents were black and that he was not biracial, and that the preconceptions people had of him found their way into his work.

He would not describe his subjects as Afro-Mexican, a label applied to them by outsiders; race, he said, is “a social construct, not a bio-empirical fact.”

In recent years Mr. Gleaton expanded his work to include other nations in Central and South America.

“What’s important about these photographs is that they gave a face to something that nobody had really thought about before,“ he said in 2007 about his Mexican photographs. “And it’s a place to begin the discussion about what we suppose Mexico to be.

“We have a stereotypical view of what Mexico is, and Mexico is many things. You can have freckles and red hair and be Mexican — and you can have very black skin and be Mexican.”