Vincent Smith, 1929-2003

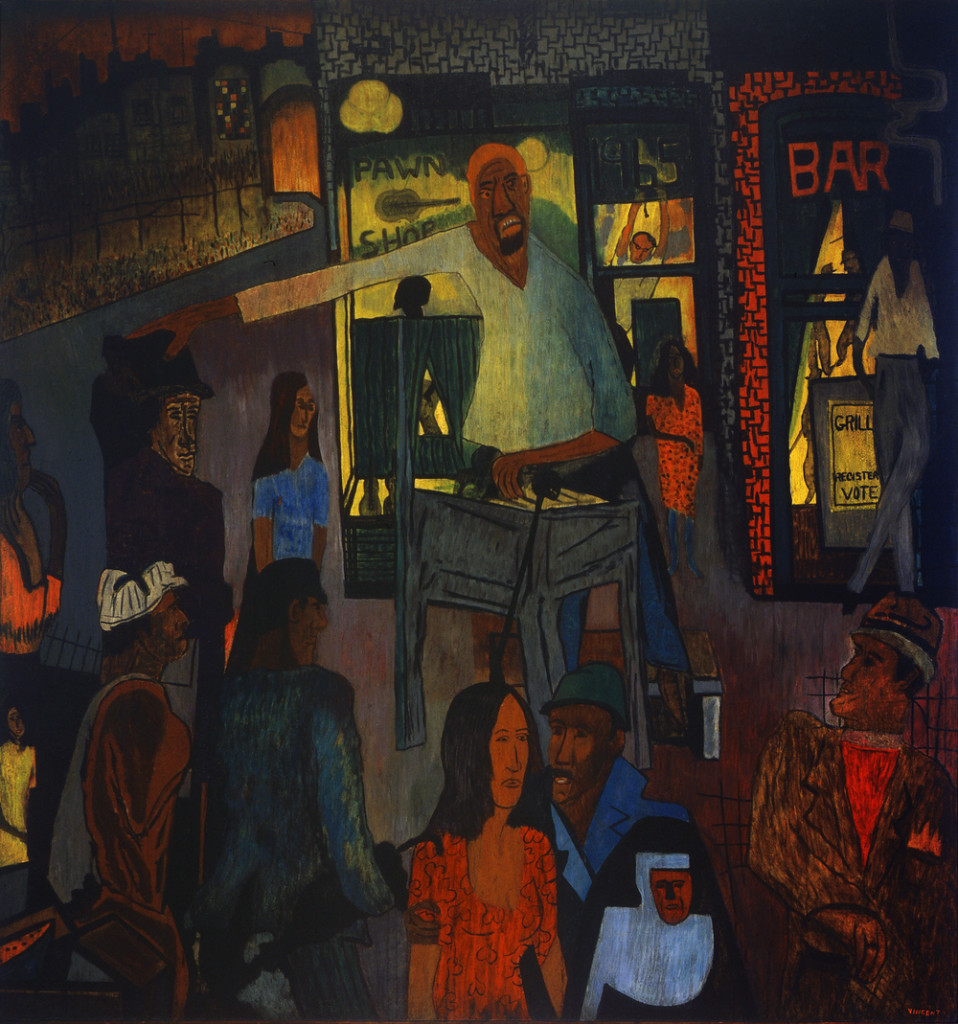

Easter Sunday, 1965.

About:

In a career that spanned half a century, painter Vincent Smith documented in brilliant color some of the most compelling events in twentieth-century America. From the be-bop-fueled improvisation of 1940s Harlem jazz clubs, to the visceral tug of civil rights workers confronting deep-seated hate with soul-clearing hope, to the creative militancy of the Black Arts Movement, Smith was there, brush in hand, bearing witness. “A figurative painter with an often subtle, social thrust, he placed his subjects in a stylized way against geometric, textured and intricately colored backgrounds,” noted the New York Times. “I always knew that I was either going to do something or do nothing,” he told American Visions. “And when I thought of myself as a painter, I dreamed of myself as a great painter.” He succeeded.

From Hobo to Artist

Attrition, 1972.

Vincent Dacosta Smith was born on December 12, 1929, in New York and raised in Brooklyn by his parents, Louise and Beresford Smith. As a high school student he preferred sketching to studying and at fifteen he dropped out. “I was a good student, but I got into trouble,” he admitted to American Visions. Soon he and a friend began hanging around the Bowery district of Manhattan. “There were hundreds of bars. There were guys sleeping all over the street, people sleeping in the back of the bars,” Smith told American Visions. “We used to go down there and hang out and drink with those guys and sit around and talk.” Many of those men worked on the railroads and filled Smith’s head with visions of life on the road. “They hopped on a train, and then when they got where they’re going, they hopped off. My friend and I thought that sounded exciting, so we went to the office and signed up.” At the age of 16 Smith began life as a hobo. He also began to open his eyes. “My first social awareness came about in 1947 while I was working on the Lackawanna Railroad—repairing the tracks, listening to the chants, visiting bars and roadhouses, and looking into the faces of the people who lived near the tracks in rural communities,” American Visions quoted him as writing.

For my people, 1965.

After hopping off his last train, Smith signed up for a one-year stint in the Army. In 1949 he returned to Brooklyn and landed a job in the post office. He was not thrilled, however; something was missing in his life. When a friend invited him to the Museum of Modern Art to see a Cezanne retrospective, he found out what it was. “Something told me when I walked into the museum that this was where I belonged,” he told American Visions. “I always knew that I would do art, but you know how you carry something around with you, and you know that one day it will surface, but you don’t know when.” With that insight, Smith set about becoming an artist. “I came away so moved with a feeling that I had been in touch with something sacred,” he was quoted in a profile on the Afro American Newspapers Web site. “For a year afterward I haunted the libraries reading everything I could get my hands on about art, literature, philosophy, religion, existentialism—you name it—I touched on it somewhere.”

The Soul Brothers, 1969.

In 1953 Smith left his postal job to become a full-time artist. He took classes at the Brooklyn Museum of Art School and New York City’s Art Students League. He traveled to Maine to study on scholarship at the prestigious Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. He learned about technique and style, history and form. Yet some of his greatest insights came from the other black artists he met. “Most people I came in contact with never knew a black painter nor had they hardly ever heard of one,” he is quoted by Afro American Newspapers. “We went through the hallowed halls of these museums…and we didn’t see anything reflect the black experience or black contribution to American culture. We knew that we were going to be scorned and ridiculed. We also knew that our achievements were going to have to take, not rage, but knowledge and skill and scholarship and long years of dedication.” He continued: “There were no black art historians, blacks with PhD’s were unheard of. Few blacks taught art in colleges in the North; there were no publications about black visual arts. There were only about four or five galleries open to us.… Yet we painted up a storm!”

Documented Struggles of Black America

Smith’s first solo show, held at the Brooklyn Museum Art School Gallery in 1955, debuted without him. “I never even showed up…,” he told American Visions. “It was like revealing your soul for the first time. You have to develop a tough hide to get through that early period; it is very rough.” His work reflected the world he moved in—New York’s avant garde music scene. “During the day I painted and at night I went to the jazz clubs,” the New York Amsterdam News quoted Smith as saying. For a while he lived in an apartment next door to a jazz musician who introduced him to famed saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker. The musical legend took a look at Smith’s work and told him to “stick to his vision,” wrote the New York Amsterdam News. Smith named a 1950s series of paintings Saturday Night in Harlem. In the 1980s and 1990s he completed another jazz series, Riding on a Blue Note. One work from that group, “Rootin Tootin Blues,” was given to President and Mrs. Bill Clinton during Clinton’s first inauguration ceremony.

The Murder of Fred Hampton, 1969.

Smith’s work took a political turn in the mid-1950s as the civil rights movement exploded. In 1954 the Supreme Court case “Brown vs. the Board of Education” ordered all public schools to integrate. After watching mobs of angry white adults taunting black school children, Smith made “First Day of School.” The Afro American Newspapers Web site wrote of the black and white etching: “In this picture we see that a mob of furious people is lashing out at the seven black school-children who have arrived for their first day at school.… We see a Klansman in his Ku Klux Klan hood and a man wielding a billy club. Other men carry a knife, a gun, a Corn liquor bottle. There is no kindness in any of their faces.” (text: http://biography.jrank.org/pages/2432/Smith-Vincent-D.html)