In this exhibition, Mapondera, who is known for his paintings on canvas and the trademark installations of tapestries weaved out of cardboard, went beyond his orthodox creative style to work with wood and metal, as well as to incorporate sound. Thus, the work appeals to more senses beyond the visual. This body of three-dimensional works is a narrative of Zimbabweans’ survival strategies or their coping mechanisms in the face of the endless hardships

Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti on recent work of Wallen Mapondera from Zimbabwe

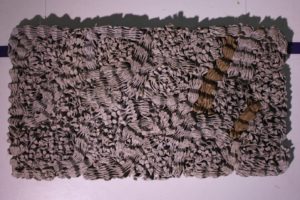

Tuck Shop 4, 2019

Wallen Mapondera

An exhibition which translates ordinary Zimbabweans’ survival strategies in the face of economic hardships

With no jobs created and no social welfare support systems in place, the status quo in Zimbabwe is that of a failed state that offers nothing to its ordinary citizens. Yet the country’s state-owned and private universities continue to mushroom, churning out thousands of graduates whose only choice is to fend for themselves on the nation’s streets, explore the extractive industry by rudimentary means in the countryside (mashurugwi) or go beyond the landlocked Southern African country’s borders as asylum seekers and economic refugees in search of greener pastures. In his Master of Fine Arts exhibition at Rhodes University in Makhanda, conceptual expressionist Wallen Mapondera translates some of these issues in a body of work that provides critical social commentary. The work renders a visual lexicon and voice to the mundane informal-sector transactions on the streets of the nation’s cities as ordinary citizens respond to the beleaguered country’s economic challenges, revealing Zimbabweans’ survival strategies in the face of hardships born out of a toxic and polarised political system and culture. In this exhibition, the socio-economic narratives of the powerless, which are normally relegated to the peripheries, do take centre stage.

Rhodes University, Makhanda

‘I will make a plan” is the most common expression of hope punctuating the people’s daily discourse in the depressive environment, hence Mapondera’s title ‘Chirema Chine Mazano Chinotamba Chakadendama Madziro,’ a Shona figurative expression which captures the Zimbabwean people’s abilities to innovate or come up with alternative ways and immediate solutions in an otherwise heavily restrictive, if not disabling, political and socioeconomic environment of seemingly endless government-induced corruption and hyperinflation eclipsing that of nations at war. Those who bore witness to the hyperinflation in the beleaguered Weimar Republic or a collapsing Iraq thought they had seen it all. Out of shame, the Zimbabwe government has had no choice, but to censor the nation’s statisticians and economists from publicizing the figures to the world. The thinking behind being that it’s better to operate in a box, sealed away from the rest of the world. However, in this age of technological advancement, information still has a way of reaching the world. In making their own plans Zimbabweans have ceased to ask what their country can do for them. America’s John F. Kennedy would have acknowledged their example.

Kudzoka Kumba, 2019

In 2000 when the Chimurenga Music maestro Thomas Mapfumo released the ‘Chimurenga Explosion’ album, two songs on it instantly became hits – ‘Mamvemve’ and ‘Disaster’. In ‘Mamvemve’, Mukanya reminded Zimbabwe’s leadership that the country they fought hard for now resembles a worn-out and torn fabric. In the song, he encourages his wife ‘to throw the toddler on her back’ and leave for the diaspora. Almost two decades later, it is this state of a worn-out fabric, in this case a tent, that Mapondera employs to capture the state of Zimbabwe in Kudzoka Kumba, for the nation still hasn’t found a way out of its socio-economic doldrums. A closer look at the worn-out tent leaves one with a lot of questions. How can one knit together a piece of fabric in tatters? How can one fix a nation as battered as Zimbabwe? Is there a way out of this political malaise and socioeconomic quagmire? It is this situation which Mukanya sums in the other song – Disaster! However, the nation’s citizens have not completely given hope as is signified by the artist’s attempts to patch the tattered tent.

Nhereka Nhereka, 2019

In the middle of 2016, multitudes of unemployed Zimbabwean graduates took to the streets in protests dubbed #thisgown, in which they were reminding their government of reneging on its pre-election promises of creating jobs or neglecting its responsibilities of creating an environment that enables them to thrive. They protested in their graduation gowns, hence the hashtag. Some of them went about doing their daily business in their gowns. That meant they were seen at street corners and intersections selling airtime vouchers and pushing carts loaded with fruits, vegetables and any wares they could sell. Two pieces in Mapondera’s exhibition capture this reality. In Kange Mbeu Kurima Kwandikona, an aesthetically enticing piece of papier-mâché intertwined by fishing lines and suspended from the ceiling in vertical lines and flowing onto the floor. For this work the artist used shredded paper with rows of student names. However, the names on the little spheres are not decipherable anymore. The title of the work speaks of desperation in an environment where academic qualifications are of no much use. In Nhereka Nhereka the artist presents a vendor’s push or pull cart on two wheels, its strong massive metal frame holding neatly weaved cardboard pieces together. At its base are rolls made from a phone directory, a reminder that even the vendors thrive on networking to stay in business. Among Hosiah Chipanga’s songs sanctioned by the state is ‘Vendor’ in which he laments the sad reality that Zimbabwe is now a nation of vendors.

Huchi Nemukaka, 2019/Kange Mbeu Kurima Kwandikona, 2019

In Huchi Nemukaka, a work made of colourful milk cardboard material threaded onto a waxed paper covered canvas, Mapondera interrogates the notion of Zimbabwe presented as the imaginary land of milk and honey in the nation’s patriotic ruling party propaganda and history. In the early and mid-2000s, as the situation in Zimbabwe regressed, the state’s sole broadcaster, the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation, embarked on a mission of feeding the nation with state-sponsored propaganda framed in Orwellian doublespeak that would make Nazi German’s Joseph Goebbels and his Ministry for Propaganda and Popular Enlightenment, or Iraq’s Comical Ali, envious. Pro-government professors from the nation’s top universities would appear on television manipulating information and making all sorts of fictitious claims as the government of Zimbabwe became adept at playing victim of the West, particularly Britain and USA, which were accused of imposing sanctions in response to their ‘kith and kin’ losing land during the chaotic Fast-Track Land Reform exercise. In their quest to blame the West, they would not utter a word on corruption, cronyism and the maladministration by the nation’s leading politicians – which are all forms of tax on the poor. One of the learned professors had the audacity to tell the nation that Zimbabwe was ‘the land of milk and honey’ referred to in the Bible, no wonder western nations were still scrambling for its resources. As such, true total liberation was not going to be delivered on a silver platter. Sacrifices had to be made. The artist questions this idea of the land of milk and honey in a state where ordinary citizens survive on breadcrumbs from the dinner tables of the elites.

At the height of Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation when shelves in big chain stores and supermarkets were empty, the sole proprietors operating tuck shops on the streets of the high- and medium-density suburbs, or in their backyards were left stocked with tissue papers, or even lemons. ‘Entrepreneurs’ could be seen selling snacks at a time when what the masses needed the most were staple foods like maize meal and rice, and basics like cooking oil which were in short supply. The artist captures these in a series of works titled Tuck Shop. One has snack-plastics squeezed or stacked between cardboard, another shows compressed cardboard egg trays, and the other two with toilet tissue rolls tightly packed between wooden frames, all resembling shelves in tuck shops. The works capture the sad realities reminiscent of the situation around 2008 when people would embark on such business for survival, with very minimal margins of profit, if at all they made something out of the trade. Very little counts for savings and there is little room for reinvesting the meagre profits to grow the business. In such a scenario, survival also entails finding something to occupy time with or keeping oneself busy as a catharsis for depression or psychological trauma.

Tuck Shop 1, 2019/Tuck Shop 2, 2019

One would think that in the toughest times, the government would be compassionate to its citizens. Yet the suffering citizens who dare to trade in the central business district where the business is brisk always play hide and seek with both the municipal law enforcement agencies and the nation’s police. They are always harassed, and their wares are often confiscated, not so much for breaking municipal bylaws by selling their goods in undesignated zones, but because the law enforcers would be eager to extort bribes from them. That is how they also make a living. Sometimes they apply disproportionate force that includes firing tear gases and live ammunition to disperse or brutalize the traders. In patches weaved in gold representing making money and red for the spilling of blood –a deliberate juxtaposition by the artist – Pahasha is a work that captures this reality in the heart of Zimbabwe’s urban zones. With residential zones depicted in black dots on white waxed paper glued on a tent, the work resembles an aerial photograph or map of the city. Whether they come from the more affluent low-density residential suburbs like Borrowdale Brook and Mabelreign or the high-density areas of Mbare and Epworth, residents of Harare still converge on the busy roads of the central business district where most transactions take place, most of them informal.

Pahasha, 2019

It does not make sense to be seen to celebrate Zimbabwe’s seemingly unending political and socioeconomic crisis. The nation’s near-collapse has led to the destruction of families as members scatter to every corner of the world in search of opportunities. However, there is something worth cherishing that has come out of that phase. The era has unleashed a generation of young creatives who have turned to found objects, due to the lack of conventional art materials. These artists have redefined art for a nation renowned for its colourful paintings, and even more for its subtractive stone sculpture tradition. Mapondera is part of this movement of young creatives upsetting the rules of art. They have shown the world that even in the hardest times and harshest environments there is a way out. This turn to found materials speaks of Zimbabweans’ creative abilities and resilience in the face of the beleaguered nation’s troubles.

Pahukama, 2017

In this exhibition, Mapondera who is known for his paintings on canvas and the trademark installations of tapestries weaved out of cardboard went beyond his orthodox creative style to work with wood and metal, as well as to incorporate sound. Thus, the work appeals to more senses beyond the visual. This body of three-dimensional works is a narrative of Zimbabweans’ survival strategies or their coping mechanisms in the face of the endless hardships. A hidden speaker filled the space with typical noises heard on the busy streets as vendors advertise their merchandise. Pahukama, a conceptual piece made of a street sign bearing the name of the late first prime minister and second president of an independent Zimbabwe welcomed guests to the supposed street scene. This body of work translates the mundane activities that we take for granted in our everyday hustles. Inspired by the artist’s personal observation, these are transactions that we are too busy to carefully look at and make sense of. It’s an overlooked or forgotten version of ourselves. A question the world always asks is why there is no meaningful mass revolt among the oppressed Zimbabweans. Part of the answer is summed up in the title of Mapondera’s exhibition which denotes the individual’s ability to ‘make a plan’- an indictment on the collective psyche as the people cannot take collective decisions or agree on the national front. Individuals think of themselves and their immediate families before thinking of the nation.

Tuck Shop 3, 2019

For the exhibition venue, Mapondera transformed the three compartments of the old squash courts building into gallery spaces. The spatial layout was excellent, with the works evenly distributed in a way that left enough room to allow audience to walk in a direction of choice viewing the three-dimensional works from different angles and positions. Besides walking into the exhibition spaces, the work could also be viewed from another angle as the audience either stood or walked on the pavilion designed for the squash spectators. In choosing the unfamiliar venue, the artist beat the monotony of always putting up shows at either the 1820 Settlers Monument or the Rhodes Fine Arts Gallery, if not the Albany Museum. I found the idea was quite refreshing.

-

Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti is a Ph.D. candidate in Art History in the NRF SARChI Chair programme in Geopolitics and the Arts of Africa, Rhodes University.

-

All images by the author

-

Courtesy Tyburn Gallery: http://www.tyburngallery.com/artist/wallen-mapondera/