Is the art critic an endangered species? Is he a mystical figure dubbed a critic? Is he white writing on blacks? Critic Athi Mongezeleli Joja is looking for answers.

Photo: Athi Mongezeleli Joja

What is the Role of Art Criticism Today?

What is the role of art criticism today? This is actually quite a common question and a nagging issue to boot. To make matters worse, this perennially invoked question is often asked contemporaneously with, or parallel to another often stated point about the deaths of art criticism. How is it possible to say both of these two things at the same time? How is it possible to ask ourselves, or bother even, about the role of something rumored to be dead?

Well, the typical responses to art criticism have been, since decades ago, an imposed fatwa on the figure of the critic itself. And now that we speak of the art criticism either with detachment towards the term, or as if we are deciphering a postmortem of a body that was never properly verified, is perhaps the result of this long skepticism towards anything resembling the critic or criticism. Mind you, terms like “criticality” or “critique” have been terms bouncing from one lip to another, in the various guises of critical theory and philosophical talk. But being an art critic, or labeling what one does as art criticism, is something that has to marked “dangerous” like a bottle containing poison. Hal Foster noticed this:

“The art critic is an endangered species. In cultural reviews in north America and Western Europe one finds writers moonlighting as critics, artists switch-hitting as the same, or philosophers unwinding, but almost no one tagged as “art critic” pure and simple. Odder still is that art critics are fairly scarce in prominent art magazines like Artforum. What has happened to this figure that, only a generation or two ago, strode through the cultural landscape with the force of a Clement Greenberg or a Harold Rosenberg?”

Francesca Pastine, Artforum, 2012/Barry Schwabsky, Words For Art: Criticism, History, Theory, Practice

After the theoretically tumultuous trajectory of the mid-century art critics in the West, in the form of the “Artforum ilk,” Foster sadly tells us that the role of the art critic has been “deemed as obstruction, and many managers of art now actively shun them, as do many artists.” In his book of collected writings, Words For Art: Criticism, History, Theory, Practice, art critic and editor Barry Schwabsky writes that “the tragedy of the honest art critic is that sooner or later the only role left may be that of the curmudgeon.” Well, I doubt very much that being characterized as temperamental is something one spontaneously resorts to when you go under the tag-line art critic. What I know is that, too often once one goes under the tag art critic, these pejorative labels roll of the tongues of people terrified by the mystical figure dubbed a critic. Someone once said, seeming me in their opening exhibition, “bitch, please don’t mess with my money.” If like we often say “familiarity breeds contempt,” it seems when it comes to criticism — when it is not praising — there’s always a difficulty even familiarizing with it. Perhaps that’s maybe one of the reasons criticism shares with death. That now art criticism — if not criticism generally — has “ran out of steam” according to Bruno Latour, simply because, amongst many things critics have become afraid of, have marked a cowardly distance from “facts.” Truth hurts, some say. Of course, the sacking of art criticism from the discursive pantheon of occidental “Big Commentary” to use Everlyn Nicodemus and Kristian Romare’s term, might have to be about the view that it was the art critic, more than the historian or anthropologist, who emerged as more centrist champion of distasteful aesthetic judgementalism.

Hal Foster, photo Artforum

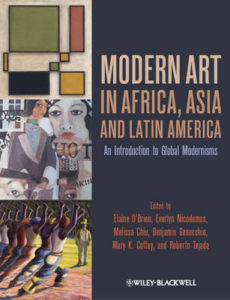

Everlyn Nicodemus is one of the editors of this book

In fact, the opposite is most likely the case. Nicodemus and Romare have pointed out that the pushing of the notion of art criticism as that of “the consecrator,” or the “watch-dogs of the establishment,” is often quite a misleading one. A true reflection of things seems to show that the reinvention of western scholarship, particularly after the post-colonial critique of its Eurocentric proclivities, has shown that claims about being “retrospect and centrifugal” as the above mentioned duo have said, contradict reality. We have not only kept criticism at an unfair distance, it has also been safe to now even normalize ridiculous phraseologies like “critical distance” in the most casual of ways. Once I read a young “arts writer” marking her distance from criticism and the critic in the most vilest of ways whilst invoking with Clement Greenberg — then highly venerated American critic who visited apartheid South Africa in the 1970s but left screams behind him, screams we can still hear today from the large white art establishment — as figure embodying total distastefulness. I wondered how this is possible that the distance from criticism has lasted so long, yet very little critical demonstration or historical evidence of why art criticism is such a distasteful figure is memorable beyond what seems like untenable reactions from a horror flick.

Olu Oguibe, Photo: Mathias Völzke

David Koloane

Perhaps contrary to Olu Oguibe’s raving praise of the post-1994 South African art establishment, and more so its art critical practices, Nicodemus and Romare, avec David Koloane, have been incensed by the patterns of Apartheid monopolization of resources have never reflected the sentiment of “non-racialism,” beyond the abstract sense of constitutionally consecrated “rights” and now, tokenism. The question of “infrastructure” is central to the discursive focus on Everlyn Nicodemus’ more general pronouncements on how “the one-eyed white selfishness…in the form of Eurocentricism and imperial cynicism… cause the black trauma.” And aught to be in fact when we think about cultural production in South Africa, as one of the interminable racist strongholds. Thus thinking about the infrastructural situation of South Africa, art criticism for the longest time reflected, quite palpably, what art historian Lize van Robbroeck once described as the colonially inflected unidirectional movement of text: whites writing on blacks.

In this case, the role of criticism and its subsequent tentative existence, remains trapped in the infrastructures of the general (national) economic disparities in which white people own (cultural) means of production to use Marxian expression. Quite frankly, it is because of these patterns of ownership — dating back to Apartheid — that resistance to a critical enterprise espousing a “ruthless criticism” to invoke the young Marx; we can begin to see the promotion of the anti-critical posture. It has been precisely this distance to criticism, or rather its capacity to be “honest” to refer back to Schwabsky, that has made criticism an enterprise or form of discursive intervention that is derided and dismissed using all kinds of ad hominem adjectives. It is these kinds of pejorative and at best, anti-intellectual postures, largely in close proximity to power, criticism appears as anachronism — a practice without a role. The best expression I personally got was when someone said, using local isiXhosa phrase, “inja ikhonkotha ezihambayo.” The literal translation of that is, a dog barks at moving cars. However, the intended message was that criticism, as some kind of a mongrel barking in the fringes of much valuable vocations, adds nothing in “discourse” but noise. But if follow the old article on art criticism in South Africa by Alex Sudheim, entitled “Man Bites Dog, Dog bites back,” we must in insist on an arts publication, devoted to or friendly towards a black art critical voice that will not only bark but bite, and bite seriously. It is perhaps through that critical bark and bite that we can revive, both a rigorous, albeit also collegial, critical practice that will be dedicated to serious engagements with our cultural production and promotion.