We should have more shows about Black creativity in the UK, exploring the dialogue between Black artists and how they are communicating the Black experience. There have been some exhibitions on Black creativity before, but often they aren’t given such a big platform or even if they are, it’s cyclic, a programming trend that’s then forgotten again for another decade. For instance, I remember in 2005, there was Kerry James Marshall at the Camden Arts Centre, Back to Black at the Whitechapel and Africa Remix at Hayward Gallery. All fantastic shows but then there was no follow up straight afterwards. I would advocate that it needs to be more consistent.

Zak Ové in conversation with Christabel Johanson

Richard Rawlings, The True Crown, 2018, courtesy the artist

I’m a passionate believer in radical integration

An interview with Zak Ové

Visual artist Zak Ové, son of pioneering filmmaker Horace Ové has curated Get Up, Stand Up Now at Somerset House. The London-based artist has worked in film, sculpture and photography, and is now celebrating pioneering black creatives from the last 50 years.

Get Up, Stand Up Now is a multi-sensory experience with new commissions alongside historical work. Contributors come from the Windrush generation; people like Denzil Forrester and then more modern highlights like Zadie Smith or Horace Ové’s feature – the first film directed by a black person.

I interviewed Zak to talk more about the exhibition, his career so far and what the future holds.

Tell us how you got started working as an artist and a sculptor?

For me it was kind of second nature because there was a big family influence. My mum really encouraged me as a kid. Television programmes like Blue Peter also influenced me. It was always there. I was more interested in filmmaking for a long time and worked as a director in television and then music videos. That led me to the States. I was there for seven years as a director for black productions. Then I lived in Jamaica for a couple of years. I was back in Trinidad with an interest in documenting the carnival and that’s where my epiphany took place. As a documenter I found it put me at a distance from the subject matter. Suddenly I found something that could speak eloquently through that practice. What’s interesting is that performance art becomes a platform for emancipation. So that really inspired me and what was interesting was looking at these traditions that were secular to the Caribbean and things like carving practices in African seem to antiquate them and put them at a distance from having any contemporary voice.

I ended up doing a residency in Trinidad and sculpting really suited me in many respects. One of the things I was interested in was bringing New World materials into the areas I thought were antiquated. A classic example is The Invisible Man (as installation I did at Somerset House). There are two-metre high figures cast in graphite that I had taken from a small wooden carving that my father had given to me as a child. That was interesting because it talked about a material that was an alternative to ebony wood. These figures represented a diaspora in that moment.

So Trinidad and carnival were really the milestone for that change.

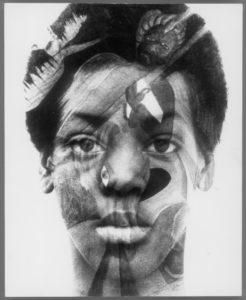

Horace Ové, Psychedelic Sister, 1964, Copyright of the artist, Courtesy of Somerset House

You come from a creative family from the Film and Arts. How important was their influence growing up?

I was born into an artistic family and brought up in an extended artistic family. Many practitioners of the Windrush generation became parental to me.

In review of this whole show, it’s interesting for me that my father had literally created a podium for so many Black artists, to honor them. I think he strongly believed that if we don’t honor ourselves, who will? Moving forward, we need to revere our own practices within institutions like this one, championing our own.

The home almost became like a seed-bed from which I could take ideas from and redevelop, re-look at and re-think about. That exploration of the past is really important for younger artists also. You might be able to develop old ideas in another medium. I think when you’re born into a world that leaves you to inherit these things you need some frame of reference. In those moments it’s really good to find examples on how to be. It’s that thing of using the imaginative process to overcome obstacles. I think art explores this so well, it’s the dialogue that excites me the most – how we use that as a process of betterment.

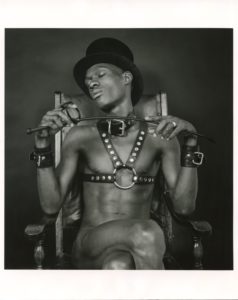

Ajamu, from the Circus Master Series, 1997, courtesy the artist

Get Up, Stand Up Now is currently showing at Somerset House. Why now than ever is it important to celebrate black creativity?

We should have more shows about Black creativity in the UK, exploring the dialogue between Black artists and how they are communicating the Black experience. There have been some exhibitions on Black creativity before, but often they aren’t given such a big platform or even if they are, it’s cyclic, a programming trend that’s then forgotten again for another decade. For instance, I remember in 2005, there was Kerry James Marshall at the Camden Arts Centre, Back to Black at the Whitechapel and Africa Remix at Hayward Gallery. All fantastic shows but then there was no follow up straight afterwards. I would advocate that it needs to be more consistent.

Somerset House has hosted 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair every year since 2013 and I first met the Somerset House team through it. I presented my large-scale installation Black and Blue: The Invisible Man and the Masque of Blackness in the courtyard as part of 1-54 in 2016. Since the launch of 1-54 and Soul of a Nation at Tate in 2017, I’ve seen audience attendance grow to these shows, which makes other institutions sit up and take note of the necessity of them. I’m really excited by the prospect of programmers writing it into their future scripts on a more regular basis.

Yinka Shonibare, Self Portrait, 2013, Copyright of the artist, Courtesy of Somerset House

As a curator for Get Up, Stand Up Now what guided you to select those key people and work showcased?

I started by looking at my father Horace’s archive. He created his first film (Baldwin’s Nigger) 50 years ago. I was inspired by his peers so then explored who their work was talking to, the next generation of artistic cousins who were inspired by them and took forward similar themes. It included musicians, filmmakers, writers, and not just from Britain. Then further down the line, today’s brilliant young talent who have been influenced by the children of my father’s generation. Each generation stands on the shoulders of their elders. Regardless of age and boundaries, I realised there was a shared experience throughout these different mediums and timelines, and throughout the diaspora. And it just excited me. This is why the show is thematic rather than chronological.

I identified and invited artists who have similarly made a significant contribution to shaping this country’s creatives and the cultural landscape in general. Pioneering work that challenges the systems of power and representation and continues to change the consciousness of society today through perpetual agitation.

How important do you think projects like Get Up, Stand Up Now are to preserving and celebrating black artistic work?

It is undoubtedly Black British creatives who have led the charge in inspiring society to embrace our music, our language, our fashion, our art. I’m a passionate believer in radical integration and it’s through culture that we become more harmonious and multicultural as a collective British people, now and in the future.

Zak Ové, Umbilical Progenitor, 2018, Copyright of the artist, Courtesy of Somerset House

Do you think the recent exhibitions and shows for black art is just a fad?

I really don’t think so. Myself and the artist Hasan Hajjaj had our studio practices side by side for many years. What was interesting was how what we did was picked up upon. Right now across the board museums have changed their remit and are now looking at the diaspora rather than just African art. One of the problems that we traditionally had was that they were just looking at antiquities and not contemporary. The whole situation changed in the United States and now globally there’s a commitment to looking at work made by the African diaspora and all its contemporary moments including work made off the continent. All these institutions are open to looking at your work as representation of what African art has become today through its journey.

In order to captivate black audiences globally and those mixed raced kids looking for a sense of identity as to who they are, you can’t just do that without really considering the greater picture of the diaspora and their story.

The other thing is that the Western world already references black culture massively. So it has a relationship to this dialogue already and the references we use to it. It is a language that Western culture in the last 50 years has been fed and grown up on. Multi-culturism in this country has permeated British culture. Within that our culture dictates artistically a lot of what’s being driven in the thoroughfare right now. Horace and his peers were making waves before me, when there was no platform at all. Some of that work is probably the most important aspects of where black British commentary begins or a reflection of it. It’s come a long way very quickly – the recognition – and that’s why I mention music as it permeated Western culture before the arts have. It’s taken a while for other mediums to become as hot on the Western art tip but I think that moment is very close.

I’m really pleased to see the attendance (of Get Up, Stand Up Now), and how people have taken that show as their own. It’s the property of the people now which is great. It makes it so worthwhile. It needs to be something more people set off to do but the process that I went through of trying to curate the show and pull everything together, I hope that others do the same. Within that what we’re exploring is our history side by side of the contemporary profile of who we are together. Look at the dialogue that was pertinent then and what needs to be pertinent now. A lot of what I was interested in was the bravery of what needed to be said and the voices that said it.

Alexis Peskine, Aljana Moons II, 2015, Courtesy the artist and October Gallery

How has black culture and identity informed your work? How conscious are you of this when creating a piece of work?

I guess it depends on what the work is. Certain works speak clearly on certain things. In other ways when I am working on pieces I am involved in the materiality and in principle this directs people to certain things. I try to be open. With somebody like myself, I lived in a household that harboured Black Power meetings. I never felt that big distance that I had to search for it.

What’s really been key was the revision of going back to Trinidad and exploring the roots behind masquerade and aspects of how that culture has kept a sense of Africa alive in an abstract. Throughout the Caribbean people have endured to keep that sense of their culture alive even at a great distance to the continent itself. This was before you had digital information to use. Through stories and rituals you kept those memories in place. What’s interesting from an artistic point of view is how you go about that imaginative landscape. It takes on something quite amazing as an abstract away from source.

I’m also very interested in the use of black music in black arts. It’s something that’s not discussed enough but traditionally a lot of our heroes are musicians and were speaking to us through music. It’s an amazing time to have an art practice that speaks about who we are and where we’re at.

So far in your career what are the highlights you’ve experienced and the challenges you have learnt from?

It was really interesting when I had to do the proposal for the British Museum. What was challenging was two-fold; it was quite a learning process. One thing was how to make a choice on what to focus on for that kind of representation. Ideally what represents “us” in that moment, it has to feel truly Caribbean and African in its presentation. The other big learning curve on that was how to make two big stilt walkers seven-metres high – so the logistics of working on that kind of scale.

There are learning curves through everything. One thing I really enjoyed in The Invisible Man installation is how to make figures like that intimate to a crowd and how at that height people can relate and ingratiate with them. When you’re exporting your culture to other situations how can you make a chance to be amongst it? I’m very excited when my work leaves me, it becomes the property of the people and not yours alone. With that installation I based it on a piece of work I grew up with in the house but hadn’t considered enough how it would relate to other people. When I took that installation to America suddenly it became about gun crimes against young black males. Suddenly the backstory of the work speaks differently to the context of the audience. When I set that up in San Francisco I had more than one mother in tears asking if it was a monument, a tribute to that.

I try and make sure there is a learning curve in most of the things I do. I enjoy the idea that things aren’t a repeat, that there’s growth always.

Zak Ové, The Invisible Man and the Masque of Blackness, installation in front of the Somerset House, 2016

What advice would you give to others starting out in the industry and making art?

I didn’t start making art in order to be in the industry – I was compelled. Most of the people that are in the show, it fulfils a sort of necessity. The idea of financial success was always a by-product. They aren’t the aspects of what drove me to becoming an artist. It was having a voice and being able to develop that voice. I would encourage anyone to do the same in that regard as it is really self-satisfying.

It is something we can all enjoy and use as a visual language. I understand the journey is difficult but let’s make it enticing. You have to be persistent and polite in trying to get attention. Don’t afraid to go back either. This thing isn’t necessarily once. Champions are made not born. Don’t give up.

What projects are you working on next?

This year ahead is an exciting one for sure. My installation of 40 graphite sculptures The Invisible Man and the Masque of Blackness opens on the 27th July in the B. Gerald Cantor Sculpture Garden at LACMA, Los Angeles and will be on view until 3 November. They have now travelled from Somerset House, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, NewArt Centre – Roche Court and The San Francisco Civic Centre – so it’s an incredible moment for them to be on display in LA.

I am also showing one of my largest sculptures Autonomous Morris in the Sculpture Park at Frieze London 2019. I grew up around Regent’s Park so it’s great to revisit with my artwork.

I’m looking forward to time in the studio, I have some more commissions in the pipeline and of course, I’ll be continuing spreading the word for Get Up, Stand Up Now.

@zakove (Instagram)

#Getupstandupnow