Because she knows all the people she makes portraits of and because she invites some of them more often to pose, watching these photos means looking at intimacy between two people. An intimacy comparable to the intimacy of the photo works of the American Nan Goldin, an artist whose work Zanele Muholi is familiar with. The ‘models’ feel free to look strong: they want to be seen.

Rob Perrée on exhibition of Zanele Muholi in the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum.

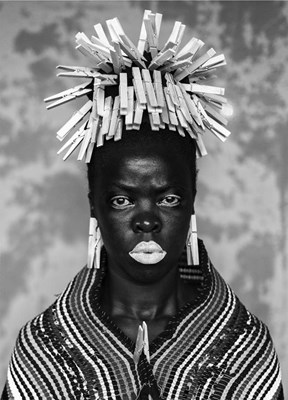

Zanele Muholi, Ntozakhe II, Parktown, 2016.

Zanele Muholi

Intimate portraits of strength

A short review

In 1996 South-Africa got a new, progressive constitution. It explicitly forbids discrimination based on sexual orientation. Ten years later the government made same-sex-marriages possible. In spite of this, statistics tell me that there are around 500 cases of sexual assault against lesbians and transgender men per year. By calling them ‘corrective rapes’ a lot of people accept and justify these cruel cases.

The lesbian photographer Zanele Muholi sees it as her task, as her duty, to document this situation. She grew up in a township (Umlazi) and came out when she was 19. She knows what it means to be a lesbian in South-Africa. A lot of her friends and women she knew were victims of abuse. She started to work for ‘Behind the Mask’, a community platform for LGBTI’s and to co-found ‘Forum for the Empowerment of Women’, a safe space for lesbians to meet and organize activities.

Installation view ‘Faces and Phases’ (ongoing project), photo Annet Zondervan.

In 2006 she decided to photograph black lesbians and transgender men. In the ongoing series ‘Faces and Phases’ she gives them a face, a respected place in society, a place in the history of South-Africa, an identity. Zanele Muholi is convinced that she – by doing that – can influence public opinion about them. The photographer as an activist. Because she knows all the people she makes portraits of and because she invites some of them more often to pose, watching these photos means looking at intimacy between two people. An intimacy comparable to the intimacy of the photo works of the American Nan Goldin, an artist whose work Zanele Muholi is familiar with. The ‘models’ feel free to look strong: they want to be seen. Because she also knows how to make strong and beautiful images – in that way comparable to those of Andres Serrano in his series ‘America’ – she manages to seduce the hesitating, somewhat discouraged art lover to focus on them. In the last room of her exhibition in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam she combines the portraits with text reports of cases of abuse, rape and killing over the last years. These ‘cold’ words give the ‘Faces’ an extra dimension. They create empathy and understanding. And gooseflesh. By putting the portraits on the wall as wallpaper, she underlines the documentary character of the works. “We don’t talk art, we talk activism and protest.“ The video ‘We Live In Fear’ – shown in one of the first rooms – gets a wider and more specific context.

‘Faces and Phases’ is an ongoing project (the first part is documented in a book that was published last year with the same title), a project that is very dear and valuable to Zumoli. A couple of years ago though she decided to start a series of self-portraits (‘Somnyama Ngonyama’), partly as a way to distract herself from the heaviness of ‘Faces’, partly as a form of introspection, but mainly as a way to challenge herself. Making self-portraits is a confrontational act for her. It awakens (bad) memories, it makes her aware of herself, of her position in the vulnerable world of lesbians and transgenders, of her blackness, of her roots. It is a way of violating herself. That is the reason why she needs a lot of preparation time to make these portraits. That may be the reason why she dresses her self up with ordinary household objects like clothespins and scouring pads. They relativize. They put humor in her work and they are allaying it. They also make guess-who-references to iconic figures – for instance out of art history – possible. An unexpected playful element. In some of the self portraits Muholi blackens her black face as if she wants to stipulate that I am not watching another documentary project. Reality changed into dramatized reality. Sometimes the extra color makes her gaze more lurid, a bit threatening.

(Left) Bester V Mayotte, 2015.

(Right) Bester I Mayotte, 2015.

The exhibition in the Stedelijk is not an overview of her work, does not want to be. It is a selection focusing on the series ‘Faces and Phases’ and ‘Somnyama Ngonyama’ (Hail the Dark Lioness). In 2009 the Museum Arnhem presented (and bought) older work. Next week another selection will be shown at Autograpgh ABP in London.

After 20 years of heavy activism Zanele Muholi’s work gets worldwide recognition and support.

It deserves it.